media and documentary 2.0, Interview

Searching for freedom

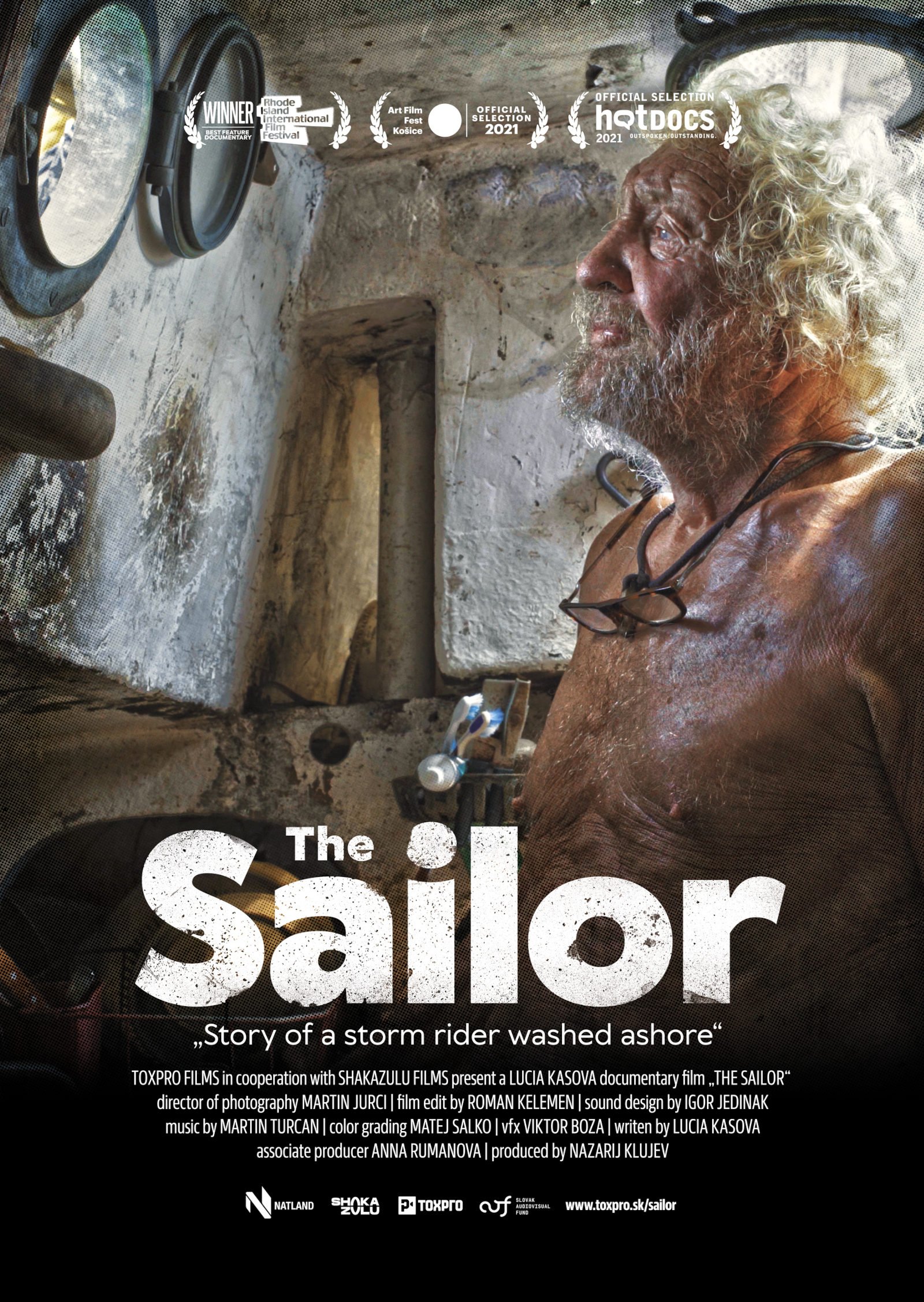

The first feature-length documentary by Slovak director Lucie Kašová, The Sailor (2021), follows an old sailor named Paul Earling Johnson and his completely free life on the Caribbean island of Carriacou. The film had its Czech premiere at the Ji.Hlava International Documentary Film Festival in 2021. The director also deals with the topic of freedom in one of her latest short films, Orchestra from the Land of Silence (2020), about the Zohra Orchestra, the first all-female orchestra in Afghanistan. The film was presented at Doclisboa last year. In an interview for dok.revue, Lucia Kašová reveals her relationship to the subjects of both documentaries and shares her personal stance on the socio-political changes that have shaped the situation in Afghanistan in recent months.

While preparing for this interview, you mentioned that you are currently in the Caribbean and will soon set sail for a few days at sea. Is this trip inspired by filming The Sailor, or did the documentary stem from your passion for the sea?

It’s the latter of the two – about eleven years ago, I sailed to the Caribbean, and I’ve been coming back here every other year ever since. From the first moment I arrived here, I haven’t wanted to go anywhere else for my holidays, and three years ago my friends and I even bought a kind of small sailboat. So yes, first I fell in love with the Caribbean, and after that I wanted to make a film about it.

Why did you choose Paul Earling Johnson as your protagonist, and how did you get in touch with him? Given his isolation on the island, I don’t imagine he’s easy to get hold of.

I wanted to make a film about the old seafaring world because it’s changing very quickly now. There’s a newspaper in the Caribbean called Caribbean Compass, which has been publishing articles from this region for years. I got in touch with the editors, and they recommended Paul Johnson. When I went to Carriacou, we ran into each other in a shop completely by chance and started chatting. We had been talking for about half an hour before I realised that he was actually the Paul Johnson I was looking for.

In other interviews you said that you had the idea for the film prepared for over ten years and that it was actually the reason you studied documentary filmmaking. Given that the preparations took so long, are you satisfied with the resulting form of the film?

I’m never satisfied with my films. After finishing a documentary, I always have the feeling that at that moment I’ve done the perfect research and that I could shoot it again. So, I’m not satisfied, but we did the best we could given all the complications we had during filming. But a documentary isn’t a feature film, so reality always enters into the shoot, and that somehow changes the final form. And I really like that about it, because a documentary will never turn out exactly how you plan.

The Sailor is rendered as a kind of observational plunge into the depths of a sailor – impressionistic landscape shots are accompanied by Johnson’s voiceover narration confessing the traumas and joys of his life. Due to this non-didactic approach, the documentary is open to different interpretations. What, for you, is the main theme of the film?

This ties into why I wanted to make the film in the first place. When I started sailing, I met some sea gypsies here who live on their half-broken boat and have just been sailing around the world for decades. This world was really enticing to me, but I asked myself what actually lies at the end of a sailor’s life – because today the Caribbean is already a kind of retirement home for old sailors. For me, the main theme was that living at sea means absolute freedom – you can only rely on yourself, and you live with the unbridled elements. But if you give yourself strict rules, even living in freedom will bind you. Johnson was born at sea and has lived there his entire life, and now he is unable to change his lifestyle and go live on land. What I found during filming is that absolute freedom puts you in chains.

Didn’t this knowledge put you off of the seafaring life that you so longed for?

No (laughs). For me, the most important thing is flexibility. When you don’t make rock-solid rules, I think that’s best.

Another big theme is Johnson’s drinking. Did it ever complicate things while filming? Would he ever be in a state unfit to film?

Many times. But it wasn’t just his alcoholism. Rather, the overall pace of life for an eighty-year-old man is completely different from ours. We would often come to his boat, and we wouldn’t even start filming because, for example, he wasn’t feeling well, or he was drunk, or he’d slept all day. So, it was mainly adapting to his tempo that was really hard. And he also couldn’t do all the things that I wanted him to do.

In one of the promotional videos, the film’s producer Nazarij Kľujev mentioned that you developed the film at a pretty hectic pace precisely because of the protagonist’s unstable health condition. How is this aspect reflected in the filming? Were you, for example, limited in the planning of the overall concept of the film?

When I first met Johnson, I got the feeling that he wouldn’t live much longer – that he was already at the end of his journey – and I was afraid we wouldn’t manage to finish the film. The first time we shot, we did a lot of physically demanding scenes, and we managed to sail his boat, which had been anchored offshore for over a decade. When we returned a year later for the second shoot, there was a big difference in his health. But we were only shooting voiceovers and a couple of scenes on the boat – and luckily, we managed that.

Given that the shape of the documentary was partially subject to the protagonist’s physical condition, were you worried that the film would be too monotonous? Did you have a preconceived dramatic plot to drive the film, or did you rely exclusively on the strength of Johnson’s memories?

First of all, Johnson had an absolutely incredible life. He has very interesting stories, and he tells them well. But like a lot of older people, he would start a story, and then a moment later he’d switch to another topic, and then another, and he never finished anything. So I ended up cobbling together one story from several days of filming. But otherwise, the overall dramatic arc of the film was pre-written, so we went according to the script.

Much of the film is based on Johnson’s narration. In your conversations, did you ever find any topics or periods he refused to speak about?

No, he’s very honest and very open. During the first shoot, he didn’t even understand why the microphone was above him, and he talked to us as if we weren’t even making a film.

This is your first feature-length documentary, and you shot it with a very small crew. Is that a practice that suits you after your experience with short films?

I got used to filming with a small crew in school, and it paid off for me in particular here in the Caribbean. I needed everyone to get to know the protagonist and build a rapport with him – so we could keep a closed, intimate atmosphere.

One of your latest short films Orchestra from the Land of Silence was presented at Doclisboa. Despite its morning showtime, the screening room was quite full, mainly thanks to several school groups that attended the festival. What does it mean to you that young people are interested in film?

The girls from the orchestra were between 12 and 18 years old, so it’s a kind of “coming of age” film, and that’s exactly how we intended it. We only filmed in Afghanistan for a week, and I didn’t know the orchestra at all, so I picked one girl and tried to make the film from her point of view. She was 15 at that time, so the film is also aimed at that age group.

But just because a film is aimed at younger viewers doesn’t necessarily mean that young people will go to see it and that it will resonate with them. But even during the screening, the audience repeatedly applauded, so the film was very successful.

The film was originally made just for the Pohoda festival. We didn’t have that much ambition, and we went into it completely blind, so I’m really happy that the film has been successful with younger viewers – especially in the context of the current situation in Afghanistan.

Although The Sailor and Orchestra from the Land of Silence are in many ways completely different, the main theme seems to be quite similar – in one you have a sailor whose absolute freedom actually binds him and in the other a group of young female musicians who, despite the patriarchal oppression of Afghan society, are still seeking their freedom.

In school, my professors used to tell me that every documentary filmmaker has only one subject – two at most. In fact, my upcoming film will also revolve around this topic. So yes, freedom is definitely my central theme.

In Orchestra from the Land of Silence it is emphasised that music has the power to connect, to break down social classes, and to reach people regardless of nationality. This may sound like a cliché, but your film doesn’t come across that way because it mainly looks at the topic in the context of Afghan history, which adds an entirely new dimension to the documentary.

I was trying to find similarities between Afghanistan and our country at the end of socialism, because I think we were in a very similar situation. Even when I was there, I felt some very similar trends in civil society. There was an awful lot of enthusiasm and a lot of young people working to change the system. To me, what has happened in recent months is comparable to if Czechoslovakia had been annexed by Russia. In Afghanistan it’s even worse precisely because of the women’s issues – in fact, half of the country is now under house arrest.

Do have any idea what happened to the Zohra Orchestra and its members after the coup?

The caretakers from the girls’ home took them into their homes – each of them must have had 10 to 15 girls at home. As for the orchestra, the Taliban destroyed all of their instruments and demolished the entire school. But fortunately, the orchestra director, Ahmad Sarmast, managed to get the girls from the orchestra out of the country. A couple days ago, the director of the girls’ home contacted me to say that they were in danger and ask if I could help them in any way. So now I’m trying to put them in contact with non-profit organisations that might be able to help secure them safe passage. For young people and women in Afghanistan, the world has ended. You can protest, but you’re standing up to someone who is holding a Kalashnikov and won’t hesitate to shoot you… And in spite of all of this, women are going to protests. The protagonist of the film, Marzia, sent me a photo of them standing in front of armed members of the Taliban, who could decide to shoot them at any moment. In that situation, it’s really hard to fight for any kind of values.

---

Translated by Brian D. Vondrak.

This article is a result of the project Media and documentary 2.0, supported by EEA and Norway Grants 2014–2021.