Unusual perspectives on stigmatised subjects: Interview with Frida and Lasse Barkfors

Jan Kinzl speaks with Frida and Lasse Barkfors on the third part of their social stigma trilogy, Raising a School Shooter.

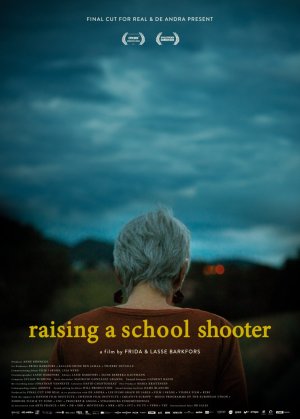

Raising a School Shooter, a documentary which follows the parents of three school shooters and looks at the very current topic from an unconventional perspective, is the final instalment in the trilogy about social stigmas by the Danish-Swedish filmmaking duo Frida Barkfors and Lasse Barkfors. Following Pervert Park (2014) and Death of a Child (2017), the newest film had its world premiere during the Danish festival on documentary films CPH:DOX where it was nominated for two prizes – Nordic:Dox Award and Politiken Danish:Dox Award.

In this interview the directors open up about their creative process and personal bonds to not only their newest film but to the whole trilogy.

---

CPH:DOX selected your documentary Raising a School Shooter to screen in a real cinema in Copenhagen on May 6th. What does that mean to you in these troubling times when a vast majority of films does not have this chance to have a proper screening?

Frida Barkfors (FB): It’s of course really, really nice and we’re truly glad for this opportunity. Actually we just found out that there won’t be any restrictions on the seating, so it‘s finally going to feel like a real screening.

Lasse Barkfors (LB): We do put a lot of work into preparing the film for a cinema screening, so we’re happy that we actually have the opportunity to show the film on the big screen with the real sound. We‘re glad we got the chance to see it with the audience.

Raising a School Shooter is the third instalment of what could be called the Barkfors trilogy. In your films you try to look on the stigmatized subjects from a different perspectives and you give voice to people who are not usually heard. Why did you choose school shooting for your newest film – a subject that has been sensationalised beyond recognition?

LB: I think the topics of all three films are very sensationalised by mass media. We’re always interested in diverse perspectives and with Raising a School Shooter we wanted to know: what have the parents done wrong? You would think that there must be something horrible that’s been going on in these families, but that’s not always the case.

|

|

Frida and Lasse Barkfors. Photo Lasse Barkfors, Nordisk Film & TV Fond

In this documentary we are basically looking at seemingly ordinary people. How did you choose these specific families? Did you try to contact more than these three families?

FB: First of all that‘s the point of the film, that they are ordinary people. Even if they made mistakes, they didn’t do anything, that would separate them from other parents. And yes, this was a really hard film to find participants for – it’s really difficult to locate them and contact them in the first place. When we got through to someone, most people didn’t reply or didn’t want to participate. We also wanted to find diversity between the participants, which made the whole process even longer.

How long did it take to start filming?

FB: I think we were looking for participants for over two or three years. We started shooting in August 2018 but in the end the whole project took over 4 years to make.

I think it is important to note, that in your documentary the school shooters do not appear at all (other than in one phone call). Was this your intention from the beginning or did the film go through different versions, in which you focused on more than the parents‘ struggles?

LB: In the end the original idea ended up being what the final film is like. But we tried to get interviews with the school shooters, because you never know what’s going to happen in such a meeting. The problem was that we weren’t allowed to interview them with camera.

FB: We wanted to meet them for several reasons – could we include them in the film, would it make it stronger? We also wanted to fact-check the stories their parents were telling us. But we are not journalists so if you want to see the full film about school shooting, our film is not it. We only wanted to bring what we think is a very important perspective to have in mind when thinking not only about school shootings but all human tragedies.

Raising a School Shooter. Photo CPH:DOX.

In all of your films your participants repeatedly share their inner thoughts and they often open up about experiences that they «never told anyone before». How did you approach this film – was it any different from Pervert Park and Death of a Child? Did it take a lot of time and energy to gain the trust of the families?

FB: I think once they agree to participate, it’s more about keeping the trust. We have to meet them as open-minded people and we want them to feel comfortable. In a way it’s quite easy, because they aren’t any different from you and I, and if I sit down and say: «I just want to listen, please tell me», you’re going to open up. And this goes for everyone, we all should do this to each other.

LB: Also, I think that most people, who have gone through tragedy, sincerely want to help others who are going through similar struggles. That’s true for all three films and that’s why our participants want to open up.

Do you think that collaborating on your films was a cathartic experience for the participants?

FB: In general, yes. When we came back to Pervert Park in Florida after the film was released, we could really feel the impact that it has had. Some of the people came to us and thanked us because we looked at them differently, which was really healing. Before the film they felt like outcasts of society living in a rat hole, but the whole experience gave them hope, that they’re actually are some people out there listening to their stories. Similarly, after the release of Death of a Child one of the mothers started opening up about her traumas, which was also a positive experience for her. It’s really nice to know that we helped a little bit.

In your films you two usually do a lot more than just directing – Frida is a co-producer and a sound recordist and Lasse is a cinematographer and an editor. Is there a specific reason why? Is this intimate approach with very few people on set helpful during shooting personal scenes?

FB: I think you’re very right about that. It’s also because we are married and in a way we know each other without talking. If there was a third person we wouldn’t be in tune as much. We don’t have to show much consideration when we are working alone and that makes it easier. In another way it’s a lot harder, but creatively it’s much easier.

In this trilogy you use a similar filming style – you usually keep the participants’ narration in voiceover and you film them during their day-to-day activities. Why do you think this style works for you so well? Did you ever try a different approach to filming which did not work out?

LB: When we started filming the pilot for Pervert Park – that was 3,5 years before the actual shooting – we had a completely different idea about how we wanted to do it. At the end we figured out that the key is to keep everything to a minimum and keep it simple as possible – keep it human. The tragedies in our films are strong, so the attention has to be on the story. Following the participants in their routines really helps us highlight that they are just as ordinary as everyone else.

What I find powerful about your films is how authentic and honest they are. Even though the subject matter revolves around traumatic tragedies, you do not artificially dramatise it.

FB: Maybe this is a silly way of phrasing it, but when I went to a film school, we talked a lot about the contract you make with the audience in the beginning of the film. We try to make our films as honest as possible and everything else has to go with that. The audience has to trust us, that we’re not manipulating and that we’re not hiding anything.

One of the main themes of your trilogy is the often dysfunctional and very complicated relationship between the parents and their child or children. Is this theme personal for you? Is that what you fear yourselves and that is why you chose these stories?

FB: The answer is both yes and no – it’s not a fear we would be struggling in our daily life, but I think that these are fears that all parents experience.

LB: I think that we realised after filming that that’s what our films are actually about, it’s not something we were going for. I think it’s about taste, we’re both interested in this topic and there are usually strong and touching stories.

The poster of Raising a School Shooter

Your trilogy took over 10 years to make, that means you dedicated all these years to a really traumatic and dark themes. I wonder if all the sad stories have had a traumatic impact on you – because as filmmakers you usually take your work home with you…

FB: It’s actually the other way around. It was very enriching, and I think it has made us better people. When you get different perspectives on life, you become wiser, more aware of the difficulties between people, and you get less judgemental. Maybe it has been hard for us, but it was the kind of pain that doesn’t make you sad at the end. Yes, it’s very tough to make films, but it’s like being a parent – when you give love to your child, you may think you get nothing in return, but seeing them happy is worth all the troubles. I think that goes for our films as well. And if the audience feels a little bit different when they walk out of the cinema, then I’m happy.

What are your next plans? Do you want to continue with documentaries about social stigmas?

LB: I think we could keep going with these films, but there is a reason why we called it a trilogy. There also has to be a point where we venture to do something else. It would feel a little bit like a machine if we continued.

Are you interested in doing fiction films?

FB: People tend to say: «oh you make documentaries» or «oh you make fiction films» but now we don’t really see a big difference between the two genres. I think that we actually learnt a lot about fiction by doing documentaries. Whether our next project will be short or long, fiction or documentary – we don’t know yet. I think what we realised during these films is that we want to be creatively free.

---

This article is a result of the project Media and documentary 2.0, supported by EEA and Norway Grants 2014–2021.