Topics, media and documentary 2.0

The True Lies of Hassen Ferhani

The festival Visions du Réel, which took place in April in Nyon, Switzerland, included a retrospective of Algerian director Hassen Ferhani. The filmmaker also taught a masterclass at the festival in which he proclaimed: “I don’t lie, but I don’t fall into truth.” What does this say about his films?

Documentaries have played with truth since their very beginnings, and it’s no different in Algerian cinematography. Hassen Ferhani is one of the most prominent figures in a group of Algerian filmmakers who at the turn of the millennium grew interested in film as a suitable and powerful medium for sharing their views on local politics, society, and the representation of truth. They founded the first film club in Algiers, which was the only film school they had and which immediately sparked their desire to make their own films. Ferhani already had experience with photography, and he made his debut as a filmmaker in 2006 with Les Baies d’Alger, a short film composed of shots of the city skyline and fictional dialogues between non-professional actors, with allusions to unemployment, social differences, and relationships. With this very first film, Ferhani outlined his specific approach to depicting reality, in which the distinction between fiction and documentary is blurred. But is it possible to capture authentic truth through “staged reality”?

In his films, Ferhani documents life and its regularities in his homeland. He creates critical depictions of a state that neglects its populace, which is forced to live on its own in a hostile environment. His film Afric Hotel (2011) tells the story of three migrants passing through Algeria, who are left to the mercy of the of the local inhabitants’ ignorance. The film Roundabout in My Head (2015) portrays the environment inside a slaughterhouse, where the characters’ unattainable dreams meet with the cold-blooded slaughter of cows. The protagonists find solace in their faith, in their spiritual connection to their animal companions, or in the small things that remind them every day that they are lucky to be alive. These diverse films guide us through ramshackle cities, neglected public services, poverty, and the inherently turbulent Sahara, which is omnipresent in Algeria as a symbol of empty despair.

Although the presented reality of life in Algeria is convincing, it cannot be forgotten that most of the scenes are artificially staged. Ferhani creates improbable events in front of the camera, which don’t shy away from fiction. He introduces his own characters, writes their dialogue, and oftentimes reworks the entire mise-en-scène. Furthermore, he often adheres to narrative techniques that don’t even attempt to be believable. His films are marketed as documentaries that tell a true account of Algerian life, yet the footage is pre-arranged or very haphazardly shot. Although Ferhani has no need to hide this reality, as a guest at Visions du Réel he defended himself by saying: “I don’t lie, but I don’t fall into truth.” So what truth does he actually present to the audience?

His films focus primarily on people – on the people who make up Algerian society but mainly on individuals. His protagonists are everything in the film. Each one has a place, each one is a character, each one matters. The truth he shows through them is not superficial and doesn’t merely make do with a critical glance. He films the truth of the person in front of the camera. Ferhani takes cinematic truth to a higher level by unnaturally staging reality in order to capture the natural behaviour of the people in front of the camera. For example, in his most recent film, 143 Sahara Street (2019), we meet random people who stop by for a tea at the protagonist Malika’s home. People who have no experience with filming are thrust into a staged environment in front of a camera and are supposed to behave naturally. However, we are not watching artificial characters but rather people who have been offered this opportunity. We observe how some of them attempt pretence while others do not, and we see how their reactions change with the awareness of whether or not they are in the frame. Ferhani then uses sensitive editing to present us with the real truth – the one that people create. As he said himself at this year’s Visions du Réel when commenting on his collaboration with his actors: “To be filmed and to be ready to give a piece of yourself is a brave act.”

Truth is a subject that is constantly analysed and questioned in documentaries. What actually is reality, and what is myth? How do these two worlds collide? Does actual truth even exist? Everyone has their own truth. For each person, it represents something different, something differently pure. Truth is facts, truth is honesty, truth is faith. Is the Lord who watches over us truth?

„People lie, but they don’t know how to lie.“

143 Sahara Street (2019)

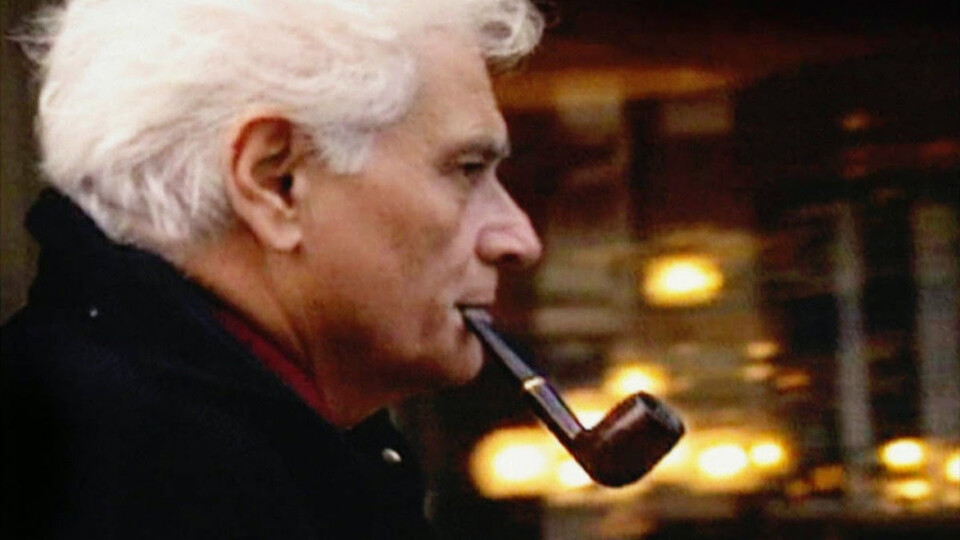

Hassen Ferhani