In the billowing night

The French colonial crimes in Réunion island are slowly brought to light.

‘Where are you from?’ How innocent a question. Yet it’s a dreaded one for many. It is one that’s separates ‘us’ from ‘them’. The question overliving racist forms of old and nesting in small talk. However blameless at first sight, loaded with meaning: You are not from here. You do not look local enough. It says: You shall never be part of us, fully. The answer given may be ‘I am from Paris’, but should it be uttered by a person with a dark complexion, it is not yet enough to qualify as true French. You may master the language. Be born in the capital. But there is no full citizenship for some people, for a full citizenship provides respect.

Fatherland

The main voice of a documentary In the Billowing Night is Jean-René Etangsalé, a man with a deep yearning for his home island of Réunion, located in the Indian Ocean not far from Madagascar, describing the very same issue: «They did not see us as French. And therefore, we do not think of ourselves as French.»

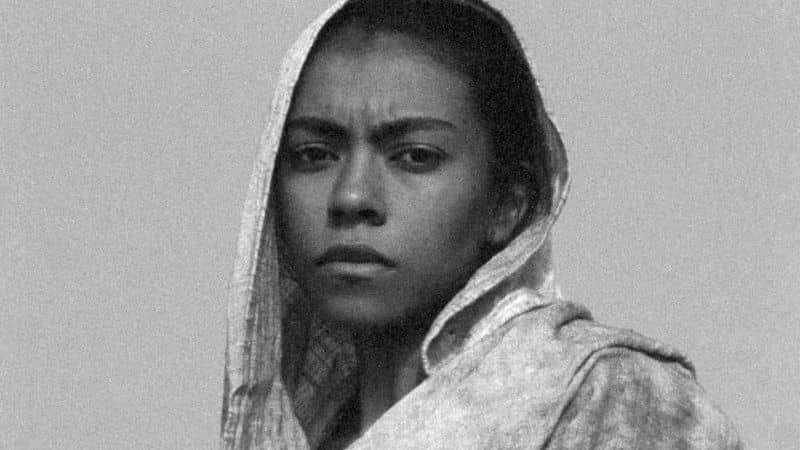

The film deals with organised and forced migration to the mainland as means of the French colonial policy. The theme of Réunion island sees the family united, as the film is directed by Jean-René ‘s daughter, Erika Etangsalé. Together they break the silence on their family history and the island’s ancestors’ pain. She speaks of «Father’s silence» and «family’s unspoken wounds».

“there is no full citizenship for some people…”

Bumidom

Réunion island used to be a French colony until 1946, when it was transformed into an overseas department. The main architect was Bumidom (Office for development of migrations within overseas departments), an agency created by French government to organise and control migration from overseas departments, to bring the low-skilled cheap workforce to mainland France, and to inhabit the depopulated rural areas.

Around 160,000 men and women from the French Caribbean islands and Réunion were trained and brought to work the less desirable jobs, such as plumbing, farming, cooking, construction work, and nursing.

The very same agency recruited Jean-René. Desiring a job during a record unemployment in the colonies due to a high birth rate after the war, he had no idea of being a part of, effectively, a displacement programme. Jean-René and many other were offered an opportunity for short-term work and later realised, this was not an individual act of kindness, but a massive operation – still quite unknown. It was not until way later that he heard of the student protestors in 1968 burning Bumidom offices.

The displacement took place between 1963 and 1982, and people finding themselves in the new country were treated as second-class citizens due to their racial difference, despite their French citizenship. The most shameful case of deportation in Réunion happened between 1962 and 1984 when over 2,000 children were stolen and transferred from their homes.

We often think of colonialism simply in terms of occupying someone else’s land, but the case here shows the complexity, and sinisterness, of it. Benedict Anderson, a famous theorist of nationalism, writes in his book Imagined Communities, which also has a chapter dedicated to Creole people, that a nationalism is a political concept in which people feel connected to other people they never met because they are able to imagine them as a single entity, hence ‘imagined’ communities. But racism shows that these abstractions don’t apply face to face. The abstraction of place of birth or language skills are nothing compared to raw material, flesh and the colour of the skin that covers it. The case here shows inhabitants not only stripped of land by aggressive newcomers, but of their homeland altogether. Not killed, necessarily, but ‘employed’ where needed. In a truest sense, human resources.

“by unlocking her father’s lips and letting him speak Creole…[the director] helps him find his voice.”

Roots of memory

The documentary itself consists mainly of a long interview with Jean-René and features an essay-like narration, accompanied by fragments of home videos, shot on Super8 film. Some of those are in black and white, which agrees with the wide shots of landscape, also in black and white to unite the roots of memory to the roots of the homeland. The camera frames infinite trees stretching over the Réunion mountains. Those mountains are named after the slaves daring to escape and taste, even briefly before being caught or throwing themselves off the mountain top, freedom. Those peaks are everything but solitary, for conscience of the country rises in them.

In the Billowing Night has a certain poetic, even symbolic quality, with a strong motif of freedom, represented by birds, Réunion harriers. There is a scene of a dreamy father telling his daughter: «I envy the birds. They can fly away. Freely, wherever they want. If I were a bird, I would fly to Réunion island.» It’s no coincidence that we encounter the recurring scenes of dead birds buried gently under the ground, representing a burial of hopes, burial of wings, burial of freedom.

The documentary In the Billowing Night is not the first work of art to deal with Bumidom incidents. There was a television film Le rêve français (‘The French Dream’) and a graphic novel Péyi an nou (‘Our Country’ in Creole). But Erika here, by unlocking her father’s lips and letting him speak Creole, in a very emotional scene, helps find a voice. The language of the playground, the language of childhood and of identity.

---

This article is a result of the project Media and documentary 2.0, supported by EEA and Norway Grants 2014–2021.