We have to start with ourselves, or nothing will change

Honeyland, a sensitive observational study of the harmony in life and nature and the possibility of its disruption, will go down in history as the first film to ever receive Oscar nominations for both best documentary and best foreign film. Both nominations were for good reason. The film combines a simple observation of reality with universally understandable themes. The creators of Honeyland, Macedonian documentarians Ljubomir Stefanov (LS) and Tamara Kotevská (TK), describe their approach to filmmaking for dok.revue.

The story of the film’s origin is quite amazing and hard to believe. Originally, you just wanted to make a short nature documentary, but then you found Hatidze, this brave woman keeping bees in the middle of nowhere. I’m interested to know at what point you said, “OK, this is our main character, let’s do this movie.”

LS: We came across a number of unusual beehives up in the mountains, and we were curious to know who was taking care of them and why. When we first found Hatidze, we were fascinated by her appearance, her character, her beekeeping, and her relationship with her mother. For the first six months we just followed her in her day-to-day life and captured her activities with the bees and her interactions with her mother.

How difficult was it to gain her trust?

TK: With Hatidze, it wasn’t hard at all. She was open to the collaboration from the beginning because she really wanted to tell her life story. She was quite lonely there, and I think that made her more willing to share. It was more difficult with the nomadic family that settled in the village during the course of the filming. It was about six months before they decided if they even wanted to be in the film at all. We eventually gained their trust through their children. They were really close to Hatidze because she was like a grandmother to them. She sang them songs and told them stories. They spent a lot of time together eating and laughing. Once the children accepted us, the adults agreed as well.

It seems like you must have found yourselves in a lot of extraordinary situations during the filming – you spent almost three years there, and in the end you had about 400 hours of material. How did you edit this down to an 89-minute film?

TK: It definitely wasn’t easy, but fortunately we discovered a good method right from the outset. We started with the basic structure and outline of the story and then filled in the details from there. This made it much easier. If we hadn’t approached it this way, we’d probably still be editing now.

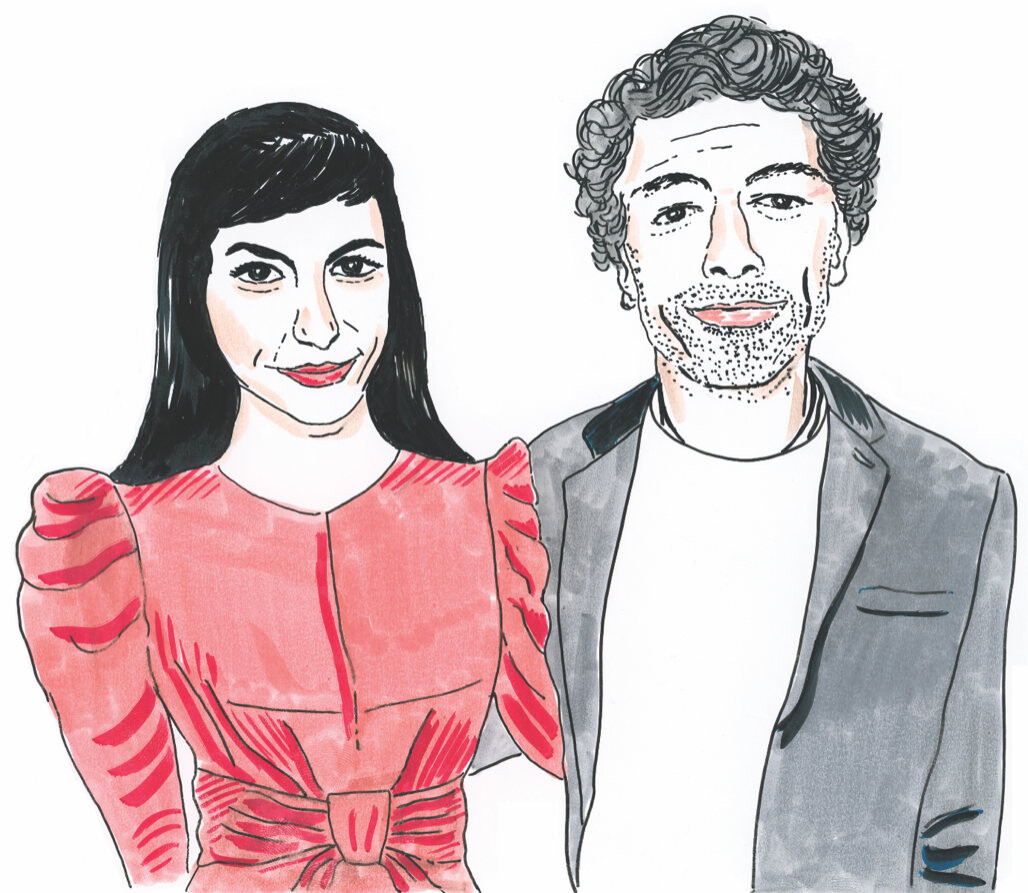

Honeyland. Photo Artcam.

Although some things in the film may seem foreign to many of us, the key motifs are deeply human and universal, such as the relationship between humans and nature and also human nature itself. The film is very complex, but it speaks a universal language. Is this at all related to the fact that you couldn’t understand your protagonists?

LS: Definitely. When they were speaking among themselves, they spoke Turkish. They could also speak Macedonian, which is how we communicated with them, but when we were shooting dialogues or arguments, you’re right, we couldn’t understand them. When Hatidze was talking to her mother we could sometimes understand the general topic of the conversation, but that’s all.

Were you surprised then during editing when you got the translations and you could finally see what they were talking about?

LS: Yes, some conversations were pretty surprising, especially those between Hatidze and her mother. In some ways it was like we were watching a different film, which wasn’t necessarily a bad thing.

You can really feel the humour in those dialogues between Hatidze and her mother. Although the film is painful, it’s also full of humour. How important was it for you to capture this humour in the film?

LS: It was crucial because there’s already so much pain and darkness in the story. Humour is an effective weapon against it.

TK: Humour a mechanism that helps people like Hatidze survive.

"In documentary, the overall material creates the rhythm... Each scene has its own tempo. You can make some slight changes here and there, but you can’t change the speed of events or the characters’ interactions."

The film has a subtle yet powerful message about man’s relationship with nature. It’s less explicit than activist environmental documentaries and has a philosophical aspect and a more human touch. How difficult was it for you to strike this balance between realistic observation and the human dimension?

TK: We were aware of the importance of finding this balance from the very beginning, so we worked on both aspects simultaneously. Neither one took priority. We were constantly aware of both sides, and we approached every shot with this balance in mind.

LS: Within the first few weeks of filming we knew what the crux of our message would be, but then we encountered several situations that were pivotal in the context of this universal language you spoke of. For example, when the trader came and offered to pay Hussein more if he’d sell him all the honey he had, that was a tipping point. This was basically a community of three people, aside from the children, and up until then they and their bees had been living in harmony. But when someone comes from the outside and says, “I’ll pay you more, just give me everything you have,” it can easily tip the balance. If the film succeeds in anything, it’s in showing how this mechanism of greed works. It’s important because in some ways we’re all like this trader. We’re all capable of destroying this harmony.

Although the trader is the primary antagonist, the family – particularly the father – causes its own share of disruption. The father acts as a mediator, and he excuses his behaviour by saying that he has to do these things for the sake of his children…

TK: This family really represents the average family. As filmmakers or observers, we don’t have the right to judge them. And why should we? It’s interesting that during screenings we noticed that a lot of viewers – especially in Europe – condemned the family. On the other hand, it was really nice when sometimes the audience recognised a bit of themselves in the characters. Because that’s the only way we can fix things – not by constantly blaming everything on others. We have to start with ourselves, or nothing will change.

"If the film succeeds in anything, it’s in showing how this mechanism of greed works. It’s important because in some ways we’re all like this trader."

LS: In Europe, many people blame the family for disrupting the harmony in the community, but only because wealthier Europeans often can’t even comprehend the type of life this family leads.

TK: If the trader hadn’t shown up, the father, Hussein, would probably have been the sole antagonist, which would have sent a bad message.

Do you think we’re losing our humility?

TK: In relation to nature – yes – in terms of knowing that you are stronger than another person or creature yet choosing to be respectful and not infringing on them. Because it’s not rewarding. In that regard, yes, we’re definitely losing humility.

It’s interesting that the film gives us very little in the way of context. There’s no introduction to Macedonian cultural or family traditions and no explanation as to why the village is deserted. What was your approach to using context in the film, and why is there so little of it?

LS: The entire film was about Hatidze in her everyday routine, taking care of her bees and her mother and travelling to the market to sell her honey. The film had no need for any kind of political or historical context.

TK: Some of the locations where we filmed were really interesting, and we had some ideas about how to include this context, but in the end, we found a better way. We’re currently working on a children’s book that will address some of this history.

Honeyland. Photo Artcam.

The movie is an observational documentary, but I couldn’t help thinking that some scenes seemed almost staged. Is that just coincidence or you actually direct the characters sometimes?

LS: No, we didn’t direct them at all. We truly just observed them and everything in the village. This impression is the result of the editing. When we were creating the individual scenes, we had a massive amount of material to work with, so we could pick very specific shots, and when you put them all together, it creates the impression of a feature film. However, some of the individual shots which seem connected are actually from different time periods. For example, the distant shot where Hatidze calls to her mother, and the mother doesn’t respond is from two years before the next shot. A lot of things also came together when we were editing the sound. It was extremely challenging, but it turned out really well. This is why the film is such a success – it’s something new.

The rhythm also plays an important role in the film. Did you find it while filming or afterward, during the editing process?

TK: In documentary, the overall material creates the rhythm instead of the individual scenes. You can try to create a general rhythm, but you can’t force it into the individual scenes. Each scene has its own tempo. You can make some slight changes here and there, but you can’t change the speed of events or the characters’ interactions.

Your film has received a lot of international awards and two Oscar nominations. How do you feel about those awards in general, and what does the Oscar nomination for best documentary mean to you?

LS: I guess it’s not really about awards or festivals or nominations for me. Though I think the review in The New York Times is relevant. They said that Honeyland was the best film of 2019 – not the best documentary, but the best film overall.

TK: For me, the three awards at Sundance are important. Sundance is an amazing, independent festival. The Oscars are more like a political campaign. Even if you win, sometimes it’s for different reasons than the film itself. During the Oscar campaign we had to do a lot of speaking in a lot of different cities. That doesn’t make sense to me because the film should be the focus, not the filmmaker. At Sundance they only care about the film, so to me, winning three Sundance awards speaks for itself.

You also received a nomination for best foreign language film, which is a first for a documentary. Where is the border between an observational documentary and a fiction feature film?

LS: I think there doesn’t have to be a border. We showed that with this film.

Translated by Brian D. Vondrak