Living in a Moral Void

On the corner of Palacký and Jungmannova Street stands a house where in the 1930s, the film star Lída Baarová used to meet with General Radola Gajda, one of her many affluent acquaintances. More than 60 years later, the downstairs café hosted three reviewers of Doomed Beauty by Helena Třeštíková and Jakub Hejna who tried to find answer to the question raised by the film – what was the main cause of Lída Baarová’s fall? Among those present were Tomáš Hrubý (TH), producer of Gottland, Stanislava Přádná (SP), lecturer at the Department of Film Studies of Charles University, and musician, historian and author of a book focusing on Lída Baarová’s love affairs Radek Žitný (RŽ).

TH – Two films focusing on the life of Lída Baarová have recently been released in cinemas. This very fact indicates that her story plays an iconic role in the eyes of Czech audiences. Baarová teaches us a lesson on the dilemmas that define our history – collaboration, striving for world importance and the ever-present Faustian dilemma of success vs. guilt. The rollercoaster of Baarová’s life does not cease to fascinate us and the film manages to capture it with great skill and purity of expression.

SP: Given the fact that Helena Třeštíková’s and Jakub Hejna’s documentary reflects on this national complex, I somehow expected a much clearer authorial voice, albeit it would have seemed as a daring interpretation of Baarová’s story. But it’s clear that the authors naturally gave preference to documentary objectivity. But Doomed Beauty is not another observational documentary – a genre in which Třeštíková excels and has a monopoly. It is rather an investigative documentary of its own kind. However, to be able to introduce a new perspective, it would have to provide space to different voices, to initiate a discussion. No matter how valuable documentary contribution this film may bring, Baarová’s moral case remains rather blurred.

“Watching Doomed Beauty is like sitting on a sofa and listening to Baarová telling her own story"

RŽ: Any reminder of the figure of Lída Baarová, especially so sophisticated and well-structured, is highly valuable. Any uninitiated observer will probably make a decent picture of Baarová, but in my view, the film’s informative value is very low. Some aspects of her life have been completely omitted. Just like Filip Renč’s fictional film, the documentary also failed to show the crucial part of her “moral” fall – not her affair with Goebbels, but her relationship with Bohumil Perlík, who accused Baarová of having reported him to the Gestapo 1939, thus being accountable for his imprisonment. The available documents from the period don’t even mention her relationship with the minister of propaganda.

TH: Watching the film is like sitting on a sofa and listening to Baarová for two hours telling her own life story. The film allows space for the viewers to decide how reliable her story is, which topics she might have avoided and which, in turn, she brought to the forefront. The effect of this method of narration consists in not drawing explicit conclusions, but it is deficient in that it does not bring up some crucial topics which Baarová herself never articulated but which play a key role in order to obtain a complete picture of her life.

|

|

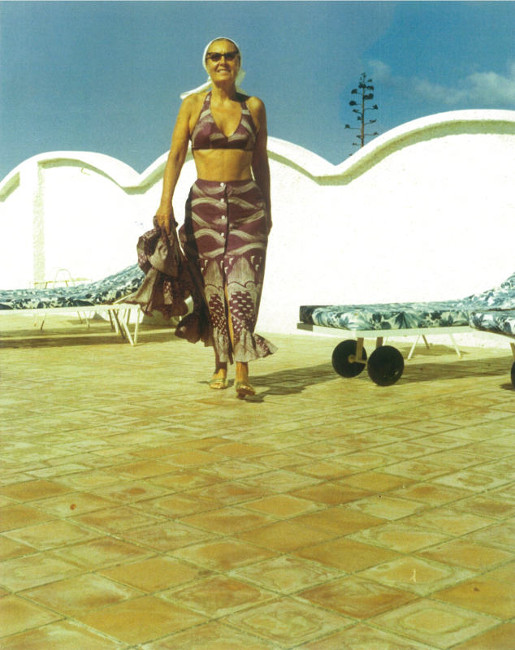

Doomed Beauty

SP: Unlike the original, shorter version of the film that was made using the same footage in the 1990s, Doomed Beauty is a coherent, well-structured feature-length documentary. However, I have to argue with the intent of “inexplicitness”, i.e. allowing the viewers to infer their own conclusions. This I see as a kind of an alibi. As a viewer, I have the right to know the opinion of the film’s authors. At points, it even seemed that they almost yielded to Baarová’s perspective. There were certain hints indicating their sympathy with this weak old lady lamenting about her life – for instance, the poetic intercuts of flying birds accompanied with gloomy music. Was this cheap cliché supposed to make you feel sympathetic? Indeed, it’s not easy to take a more decisive attitude given the applied narrative structure. The entire concept would have to have been different, focusing directly on the controversial nature of the topic, which would require confronting views and plurality of opinions.

“Baarová was her own victim”

TH: For example, Baarová fascinated director Petr Hátle as an old lonely alcoholic. His film Lída Baarová’s Virginity did not analyse her life choices leading to her success and eventual fall. Třeštíková and Hejna focus on Baarová’s perspective, without delving into the issue of whether she betrayed the nation or moral principles, or her own interpretation – that she only was a naive and confused young girl – and including it into their narration scheme. Hubač and Renč tell her story as the traditional tale of rise and fall, but distort and modify the reality, and use cheap methods of narration not dissimilar from the works of the so-called exploitation cinema.

RŽ: I don’t understand why Baarová is taken for the mascot of all the artists who paid their price for being born at a certain time and consequently being forced to act in certain way. I believe that our history has many more exceptional stories to offer. For instance, that of Anna Letenská, a film actress who died in a concentration camp, or Čeněk Šlégl, who apparently sacrificed his life for his family. Not much is known about Karel Postránecký who dedicated the money earned for his engagement in anti-Semitic political propaganda on Czech Radio to support anti-Nazi resistance. If there is a trend of being reminiscent of this period in our history and its notable figures, we should not forget real heroes. And Baarová is not one of them – she was her own victim.