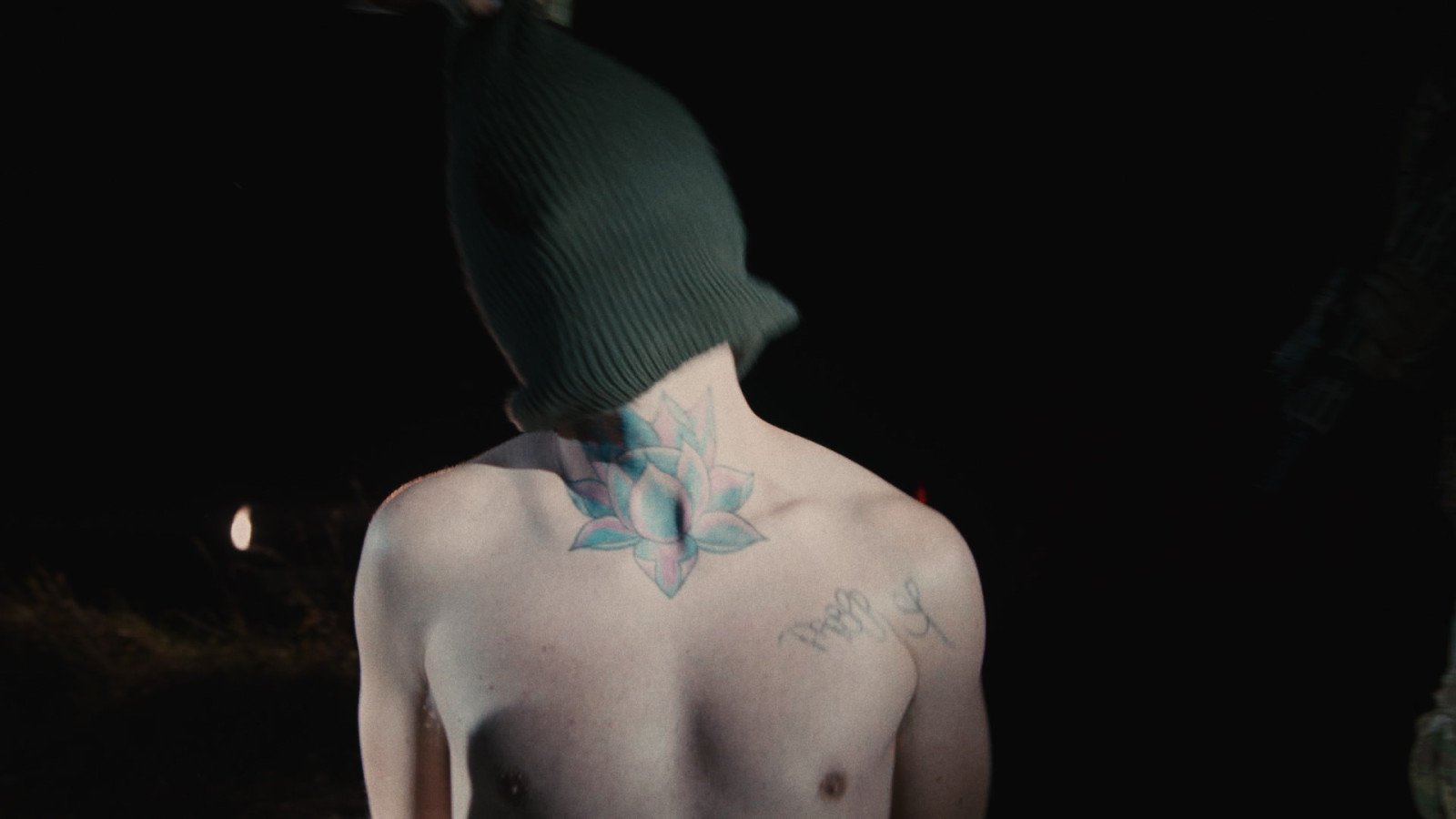

Jan Hušek. Becoming a man is a never-ending process

In Bedwetter, Jan Hušek tackles the issue of masculinity, not only as a director but also as the film’s protagonist. What does it mean to be a man? How do you become one? And is it possible to bridge the generation gap?

Bedwetter won Best Cinematography at last year’s Ji.hlava International Documentary Film Festival as well as both Best Documentary Film Directing and Best Film at FAMUfest. Hušek’s distinctive filmic confession combines a diary format, internet videos, and live-action re-enactments. At the same time, it comes across as a kind of film therapy in which the director faces personal fears, overcomes physically and psychologically demanding challenges, and demonstrates a high level of self-reflection.

Is there such a thing as an ideal man? And what defines one?

I think that’s for each individual to determine. I’m basing this on the ten or so talks we had after the screenings. For some people it’s responsibility, for others it’s self-confidence or confidence gained through experience – that’s what I often say. Life itself will offer some experience. But becoming a man, and generally becoming a more sensitive person, requires us to seek out experience. I don’t think there’s a particular set of qualities that a man should have, but I do think some things overlap, and this is true for people in general. These are things like responsibility, self-confidence, and even confidence in self-consciousness.

This sentence was also uttered by Igor Chaun in the film. In an interview at the Ji.hlava Festival you said that you are now a man. Has that changed since then? Has it evolved?

I always think of Karel Vachek. Back when he was still alive, I would be his workshop, and he would always get irritated and basically try to talk me out of making the film. I was in an angry period back then, and I felt like the whole world was against me. I kept feeling the need to defend myself. And Vachek told me that you could also say you only become a man right before you die. I always think back on that, because I’ve realised it’s a never-ending process. And I’m glad for that; I actually enjoy it. I didn’t think I was going to just make a film and settle the question for good. But it was a kind of gateway for me. I had a certain feeling that I wanted to change, and I wanted to know what I had to do to change it. It’s a never-ending process, but I needed to take this step in the form of filmmaking.

|

Jan Hušek is a graduate of the Department of Documentary Film at FAMU in Prague. As part of his thesis project, he made a short film under the pseudonym Jeto Polák entitled Fuck You, I Love You, in which he comes to terms with a break-up with his girlfriend through a dialogue with Igor Chaun. Hušek’s feature-length debut Bedwetter is his graduate film. |

What do you think Karel Vachek would say about your film if he saw it?

I think he’d find something there. Something I’m not even aware of. And it would have a different meaning for him than it does for me. He’d probably like it – just in a different way. In general, a twenty-year-old perceives things differently than an eighty-year-old.

“The birth of a man’s ego is a lot harder than getting a driver’s licence.”

It took more than five years to make the film. During that time, did you think about expanding the thematic scope? Perhaps to the overall position of men in society?

I thought about possibly expanding it, and I think I even managed to do so. When I talk to others, a lot of them suddenly find themselves asking when they became men or if they are even men at all. I think that’s great. Or someone will say to themselves that they’ve never in their life been in a sleeping bag in the woods and that they should give it a try. That makes me happy. But as far as the debate about the position of men in society, I didn’t really want to go that direction, although it did cross my mind. I didn’t want to be an intellectual type of director. I suppose I could if I were older. I don’t feel like evaluating society just yet.

Is the very necessity of becoming a man a kind of burden? And what role does generational succession play in this? In the film, you have scenes with your father and grandfather.

This transition is a painful process – and not just for men. Growing up as a woman is a painful process; growing up as a person is a painful process. I like Mnislav Zelený’s analogy. He said that a woman becomes a woman when she begins menstruating, and a man has to repay her blood debt. And that’s why for us men it’s often about pain and overcoming it. It’s a process of the death of the boy’s ego and the birth of the man’s ego. In my personal experience, it’s a lot harder than, say, getting a driver’s licence or graduating secondary school.

There’s a sequence in the film made up of internet videos full of motivational phrases and tips about how to be a proper man. In the Czech context, the leading representative of this way of thinking is Marek Kaleta, who puts career success and making money above all else. Did you feel any pressure from this oversaturated media space?

Yeah, and I still feel it today. Though it’s not about being a man; it’s about making money. A lot of other people represent the same thing as Kaleta. They say the same thing over and over. If you work hard, you’ll make money. And if you work really hard, you’ll make a whole lot of money, and then you can have a lot of things. I feel a lot of pressure because of that, but I think it’s more about finding something you enjoy, and the money will come later.

As far as my internet role models, though, they all come from the Navy SEALs, which is connected with my childhood. I’ve always liked and been fascinated by the SEALs. They’re an elite unit, and they have extremely challenging entry requirements. When I looked up former Navy SEALs, like David Goggins, the world of ultra running opened up to me.

Nowadays we often hear the term “crisis of masculinity” being bandied about. What is this crisis? How do you understand it?

I didn’t make the film because I felt a crisis of masculinity. But I didn’t know what to hold on to, where the first step should be. Our fathers’ generation was very money-oriented, partly because of the situation here in the ’90s. They weren’t home a lot and didn’t have much of a hand in raising us because they were out earning money. So my generation never had much contact with masculinity. We didn’t have role models.

I recently heard Jaroslav Dušek say in The Four Agreements that the long era of men leading the world is coming to an end, and now women can lead too. So men have to become more sensitive, and this confuses them. They may think they’re losing their masculinity. I personally don’t think that. I don’t feel that way. Maybe the crisis of masculinity concerns men older than me.

In the film, you attempt to reconnect with your father. His reaction is passive, and he shuts himself off from communication. We can assume that his father didn’t communicate with him either. Is there anything you can do about that?

Well, yeah, there is. I have to be better than my father. When I have kids, I’ll have to be more sensitive toward them. But at the same time, it was a great experience. I’ve forgiven my dad, and the process is ongoing. It’s helped me a lot. I was angry with him. If I hadn’t made this film, I would have woken up at forty and found I was behaving just like him. There is a way out of this. There always has to be somebody to break the cycle.

A lot of people in your film mentioned that the way to become a man is through pain. Was filming itself a painful process for you, whether it was the preparation phase, production, or post-production? Did you suffer?

It was painful, which is part of the reason it took so long to make. My vision was to finish the film in two years. I find that funny now. There were a lot of moments when I doubted whether to even release the film. I admitted to the crew after the premiere that there was a period when I was considering deleting the film after we graduated.

I really doubted myself: Do I even have the right to make something like this? Isn’t it too egocentric? What if I get ridiculed? But then I thought: Who else should do it but me? It made sense to me. The editor, Jakub Jelínek, played therapist for me many times. We’d go through my Facebook statuses, which had helped me when I wrote them. I didn’t identify with a lot of the older statuses. When he read them aloud to me, I felt ashamed. It was all very challenging, both physically and mentally, but I’m glad I went through with it. If I had made a film about someone else and had just been behind the camera, I would have missed out on a lot.

Film is a kind of therapy for you. Would you be able to film in a different way?

I could probably manage it, though I haven’t really tried. I can think of one example, when I was making a music video for the band Opak Dissu. I’m sure a different kind of work is right around the corner for me. I don’t think I want to make another film about myself unless something major happens to me. I don’t want to make endless sequels to this. But even though I won’t be in my future films, I’ll surely see myself in certain characters. I think it’s the same for every director.

Bedwetter also features live-action reconstructions of situations you experienced in the past. In one scene, you are aggressively pulled out of a car by your father, who is played by a self-defence instructor. In another, you meet up with an ex-girlfriend, played by a friend of yours. Was opening these old wounds cathartic?

I wanted to use the situation with the car to illustrate what I suffered in the father–son relationship. We originally wanted to have a fifteen-year-old actor play the character of my younger self. It might have looked better aesthetically and been more believable, but I’m glad we decided against it. I needed to experience it myself. I was really scared, but it was great to experience it and confront it; it had an immediate therapeutic effect.

I didn’t want to put the girlfriend scene in there at all. A classmate of mine came up with it. He thought the film lacked some kind of contact with women. I spent a lot of time thinking about how to approach it and what I should shoot. Then I remembered that incident where I met up with an ex-girlfriend. So we re-enacted the scene. It wasn’t cathartic until we got into the editing room; then I laughed at the situation. You suddenly get some perspective. But when I was there, in that situation, I felt terrible. I even thought about suicide, though fortunately not for long.

“I’m glad women like the film. I didn’t want to make a film just for guys.”

I like that the film engages in a dialogue with the audience – it’s not didactic. What was the collaboration like in the editing room? How much material did you have to work with? And when did the final form start to take shape?

There wasn’t that much material – something like thirty hours, maybe even less. Over the course of those five years, there were several versions of the film. The version I put together for my bachelor’s thesis was different, and then we filmed some more and re-edited. We only finished the last scene a week before the final deadline to submit it to Ji.hlava. We were tweaking it until the last moment. At one point, the editor told me to quit meddling and went out to his cottage to finish it, saying he’d be back in two weeks. He called me maybe twice during that time, but he didn’t send me anything.

I had to get used to the new version; it was completely different from all the previous ones. Then we had one last week together to finalise everything. One night, the editor said that we could either go home now and watch the final result for the first time the next day, or we could go get some beer and watch it right away. So, we got some beer. We smoked a joint to go with it too. I don’t normally smoke much, and it suddenly gave me the perspective I needed. I took advantage of this and started watching myself in the film as a stranger. As we watched, we took notes on where to edit the film and so on. And the next day, the editor incorporated our notes. It really helped a lot.

Then when I looked at myself in the final part of the film, I thought, “Well, if this guy says he doesn’t feel like a man after all that, I just don’t believe him.”

How many people did you consult with in the end?

Studying at FAMU taught me one thing: You can never have too many consultations. One teacher will praise your film, another will tear it down. Sometimes the opinions are absolutely contradictory. You don’t know where you stand. I take advice from people I trust, and I like to hear their opinions.

The film draws on the aesthetics of internet culture and videos. It has a lot of intertextual elements, similar to BANGER, for example. Do you see it as a refreshment of film language? Is it meant to bring the film closer to the younger generation?

In the beginning I didn’t think of the film as a refreshment for the younger crowd. As young filmmakers, we automatically did things our own way. Of course, the fact that our editor had just done BANGER also factored into it. The way I saw it was that as young people we can’t avoid the internet, and I didn’t avoid it in my personal story either. So, logically, I felt that it belonged in the film as well. I wasn’t trying to imitate or draw from something. I do things my own way, and I enjoy discovering it myself. Young people also enjoy the film because of the humour. And I’m especially glad that women like it too. I didn’t want to make a film just for guys.

Even though you’re the director, in the film you’re often directed by other people, whether it’s Igor Chaun, the army instructor, or your cinematographer Patrik Balonek. How did you work with this dynamic, and how much freedom did you give the crew?

As far as the actors are concerned, I enjoyed going to them with the idea that I needed advice, letting them guide me, and seeing what came of it. That was my approach. Some people said after watching the film that it was a shame that I didn’t confront the others more and that I gave everyone the benefit of the doubt. For me, however, it was logical. Why would I confront them when I was only in some sort of fact-finding process? I enjoyed letting the actors guide me, and their choices were instinctive. I’ve had good luck finding great people.

Once, while we were filming the army sequence, I lost track of the crew during one training exercise I was doing. It wasn’t possible for them to film me the entire time. Suddenly, after six hours in the woods, I realised that I hadn’t seen the cinematographer and sound engineer for several hours. I figured maybe they were filming something; surely they weren’t sitting on their asses. I just let it go, but the situation itself fascinated me. As the director, I should have been in control, but on the other hand, there was nothing I could do about it. It was meant to be, so I just went with it.

And it worked out great. The cinematographer understood the whole situation and took over my role, even letting the soldiers kidnap me. Then he was afraid he might have got carried away, and I don’t blame him.

This also applies to the editing room, where I sometimes felt embarrassed and wanted to cut some passages. The editor, on the other hand, thought it was fine, so I left it up to him. It’s hard to have perspective on yourself.

The film won the award for best cinematography at Ji.hlava. Did you and the cinematographer search for an artistic key?

It was completely impulsive. Someone later said the film lacks wide shots, but I didn’t feel that way. I enjoyed the fact that it was all spontaneous. We let it flow. I was in front of the camera most of the time, so I didn’t have that much control over it. Of course, there are a few shots I would shoot differently now, but only a few. Everybody in the crew really enjoyed this style of filming. The cinematographer even said he was bummed that it was over.

You’re not credited in the film under your pseudonym Jeto Polák. Does this have something to do with the journey you completed?

It’s really funny, but once again it just comes down to spontaneity. At some point Facebook warned me that if I didn’t change my name to my legal name, they would cancel my account. So, I changed it, and I wondered what that would do to me. There’s a certain path to myself here. I had given myself a lot of nicknames because I didn’t agree with the fact that I had the same name as my father. When Facebook forced me to change it, I felt there was a certain maturity in it. Now I can’t imagine being Jeto Polák anymore.