Documentary Reenactments: A Paradoxical Temporality That Is Not One

Reenactments, the more or less authentic recreation of prior events, provided a staple element of documentary representation until they were slain by the “verite boys” of the 1960s (Ricky Leacock, D.A. Pennebaker, David and Albert Maysles, Fred Wiseman and others) who proclaimed everything except what took place in front of the camera without script, rehearsal or direction to be a fabrication, inauthentic. Observational or direct cinema generated an honest record of what would have happened had the camera not been there or what did happen as a result of recording what happens when people are filmed. Observational temporality possessed the flat, one-dimensionality of real time divorced from its past but it gloried in the complex dynamics of interactions whose future was unknown at the moment of filming.

Times have changed. Reenactments once again play a vital role in documentary, be it of a Solidarity movement that cannot be filmed in Far from Poland, a murder for which radically disparate accounts exist in The Thin Blue Line, the schematic simulation of a harrowing escape from captivity in Little Dieter Needs to Fly, or events during the final days of Salvador Allende’s socialist government in Chile, Obstinate Memory. Apart from the occasional controversy such as that surrounding the use of reenactments that cannot be distinguished from actual footage of the historical event, a turn that shifts the debate from strategies of representation to questions of deceit, reenactments are once again taken for granted. They pose, however, a number of fascinating questions about the experience of temporality and the presence of fantasy in documentary. These are the issues this essay explores.

Mighty Times: The Children’s March (Robert Houston, 2004)

Reenactments occupy a strange status in which it is crucial that they be recognized as a representation of a prior event while also signaling that they are not the representation of a contemporaneous event. They stand for something but are not identical to what they stand for. This is akin to the status of play compared to fighting, at least in the formulation provided by Gregory Bateson in his essay on “A Theory of Play and Fantasy”: “These actions in which we now engage do not denote what would be denoted by those actions which these actions denote.”1) The controversy surrounding the 2004 Academy Award short documentary winner, Mighty Times: The Children’s March, involved charges that reenactments blended imperceptibly with authentic footage of civil rights activity in the 1960s South, as did archival footage of other events such as the Watts Riot in Los Angeles. Viewers must recognize a reenactment as such if issues of deception are to be avoided and if the reenactment is to function effectively, even if this recognition also dooms the reenactment to its status as a repetition of something that already occurred, elsewhere, at another time and place. Unlike the contemporaneous representation of an event—the classic documentary image, where an indexical link between image and historical occurrence can be claimed—the reenactment forfeits its indexical bond to the original event and yet, paradoxically, it draws its fantasmatic power from this very fact. The shift of level prompts awareness of an impossible task: to retrieve a lost object in its original form even as the very act of retrieval generates a new object and a new pleasure. The viewer experiences the uncanny sense of a repetition of what remains historically unique. A specter haunts the text.

What constitutes a lost object is as various as all the objects toward which desire may flow. The working through of loss need not entail mourning: it can also, via what we might call the fantasmatic project, evidence gratification, or pleasure, of a highly distinct kind. Documentary film generally entails a performative effort to register what is or will immediately become past in a mise-en-scène produced by a desire to retrieve, re-experience, master or enjoy. Reenactments double this performative dimension by hinging themselves on the viewer’s awareness that what is represented represents what has already occurred.

As a collective activity fantasy—from the folie a deux to documentary film—functions as ideology.2) It provides the psychic foundation for those imaginary relations to actual social relations through which we invest ourselves in the world around us.3) Fantasy thus functions as a structuring agent, something that reshapes what it takes up and it is this action that becomes of key importance. As Jean Laplanche and J. B. Pontalis note, “…it is the subject’s life as a whole which is seen to be shaped and ordered by what might be called, in order to stress this structuring action, a ‘phantasmatic’ (une phantasmatique).”4) In this sense, fantasy is where the subject represents and becomes itself. And yet, the subject finds itself dispersed throughout the fantasy, in the mise-en-scene, or in the syntax: “…all distinction between subject and object has been lost.”5) It is a subject that is not one, but one that is now subject to and the subject of desire. The dispersed subject, like the reenactment, draws near to the gap between then and now, seeking to go through the motions that will allow it pass across but finding instead the new pleasure that constitutes the phantasmatique itself. Fantasy always entails a temporal trajectory, a version of narrative structure and action, in the service of desire. The mise-en-scene constructed is one that straddles the narrow gap between need and desire. In such a case, shared fantasy or ideology is no longer a subject for idle curiosity.

As classically understood by Laplanche and Pontalis, fantasy operates within another gap as well, in the space between before and after: the before of what has already occurred, namely, the pacification of a need, and the after of a new gratification, occasioned by the fulfillment of a desire. This marks the fantasmatic as, in fact, “the moment of separation between before and after.”6) It inaugurates the lived experience of temporality in the form of desire. It is where we fill time with the duration of a longing. It is the moment, or, better, the duration of a moment between “the object which satisfies and the sign which describes both the object and its absence…”.7) The latter does not provide the same type of satisfaction as the former, but, as the “between” extends across the mise en scene of a fantasmatic space, it comes to be entirely real psychically.

Capturing the Friedmans (Andrew Jarecki, 2003)

A stunning example of this process unfolds in Capturing the Friedmans. The film explores the complex web of family relations and submerged desires that lie behind the formal charges of pedophilia against the father, Arnold, and his son, Jesse. They are alleged to have fondled, seduced, abused, raped, and sodomized dozens of young boys who took computer classes in the family’s home. Andrew Jarecki draws on home movies, shot over the course of the family’s lifetime, video diaries, shot mainly during the period of tumult precipitated by Arnold and Jesse’s arrest, television news reports and Jarecki’s own interviews with most of the involved parties. If the trial of Arnold and Jesse sought to achieve the either/or clarity of guilt or innocence, Jarecki is far more concerned to capture the ambiguity and confusion that this very process produces within the family.

Une phantasmatique, as the duration of a moment between the object of an original satisfaction and the sign that describes both this object and its absence, occurs within the mise-en-scene of some of the family’s more recent video diaries. These are scenes shot by sons Jesse or David as they attempt, with their father, to reenact the form of spontaneous family togetherness that has become a lost object. Home movie footage, shot in Super 8, has shown the boys and their father in moments of carefree bliss, dancing, singing, and generally cavorting together with a casual acceptance of the camera as an embodied participant (it is held by a family member). The recent video or digital footage—distinguishable from the home movies by its absence of film grain, lack of color fading, and greater contrast—however, demonstrates the impossibility of stepping into a temporal river for the first time twice. The boys and their father are markedly older, their dancing and clowning slightly forced, the father visibly burdened by the weight of his arrest, and their mother more emphatically excluded than simply absent. The video footage is the sons’ attempt to reenact their own past. They are clearly aware of their attempt as a reenactment rather than a genuine return to a lost object and irretrievable moment: the video footage stands as sign that describes both the lost object (the unqualified pleasure of physical cavorting that once was theirs) and its absence (the effort that must now be made to reenact what was once spontaneous exuberance). This is nowhere more evident than in the refusal of Arnold’s sons to see his haunted and mortified expression, an expression, which, if acknowledged, would thwart their own desire to go through the motions that will generate the compensatory pleasures they desire.

These extraordinary moments, in which the participants attempt to will themselves back to the past and yet know very well that the effort must fail, border on the work of mourning cinema, or video, makes possible. They compound that semi-acknowledged work with the production of a fantasmatic pleasure, for the sons at least, that lessens the sting of that which is lost and cannot be retrieved. They go through the motions that locate them within a mise-en-scene of desire, a fantasmatique their mother can no longer share. They do, once again, now, what they once did, then, and derive from this act not the original satisfaction of a need but the gratification of a desire that stems from the sequence of images, or signifiers, they fabricate for themselves.

Laplanche and Pontalis stress the importance of a temporal convolution in which the past and present are inextricably woven together. Fantasy is not the mere retrieval of something past, not the recovery of a real object, or, as in the example they adopt, not the milk a baby may have ingested but “the breast as a signifier…” (italics mine).8) What was once an external object transforms into an internal image or signifier. The signifier bears an emotional weight. What fantasy restores in this example is not the act of actually obtaining the mother’s milk, “not the act of sucking, but the enjoyment of going through the motions of sucking.”9) Such motions, necessarily corporeal, produce, when successful, their own pleasure.

This enjoyment or pleasure resides in the realm of psychic reality. Like the reenactment, it involves a pleasure that comes from “going through the motions” associated with a past event but doing so in a distinctly different, fantasmatic domain. Pleasure flows from an act of imaginary engagement in which the subject knows that this act stands for a prior act, or event, with which it is not one. A separation that entails a shift from physical needs and their pacification to psychical desires and their gratification, between before and after, then and now, is as integral to the fantasmatic experience as it is to the efficacy of ideology.

Chile, la memoria obstinada (Patricio Guzmán, 1999)

A telling moment of this sort occurs in Chile, Obstinate Memory when four of the personal bodyguards for President Allende reenact their role in a Presidential motorcade prior to the military coup d’etat that toppled his government on Sept 11, 1973. Guzman cuts between the footage of the men reenacting what they used to do and shots of them actually guarding Allende some thirty-five years ago. Then, Allende and others sit inside a large, topless black limousine, crowds line the way, and the four men trot alongside, eyes scanning the surrounding scene, as each keeps a hand in contact with one of the four fenders of the car. Now, the men walk alongside an economy size, red, hard top sedan, on a deserted country road, with no crowd in sight, but each with a hand in contact with the car and their eyes once again scanning the surroundings.

At one point Guzman freezes the image of the motorcade “then,” and the guards identify themselves and compatriots from the still image. The authentic image becomes remote, an instigation for memory and identification, whereas the reenacted image allows the men to “go through the motions” of guarding the President one more time. It clearly does not fulfill an official state need this time; instead it gratifies a personal desire, it makes possible “the enjoyment of going through the motions of guarding,” as it were, when guarding itself remains squarely lodged in the past. Nothing captures this temporal knotting of past and present better than a close up image of the hand of one of the guards slowly fluttering up and down on one of the half-open car windows: the rhythm follows from the cadence of his gait beside the car but the camera’s close up view of his delicate grip, the rise and fall of his fingers, and the overt absence of an engulfing crowd attest to the psychically real but fantasmatic linkage of now and then.

Despite the gulf between now and then, and as a precondition for the gratification reenactment, like fantasy in general, can provide, the subject becomes “caught up in the sequence of images” that populate the mise en scene of desire. This holds for the bodyguards in this striking scene from Chile, Obstinate Memory, just as does for the Friedman sons and father in their video reenactments, but it is also true of the viewer, immersed in an experience in which he knows very well that the reenactment is not that which it represents and yet, all the same, allows it to function as if it were. Above all, however, the filmmaker is the one caught up in the sequence of images; it is his or her fantasy that these images embody. The filmmaker need not be physically present in the image, as she is in many participatory or interactive documentaries. “… [T]he subject, although always present in the fantasy, may be so in a desubjectivized form, that is to say, in the very syntax of the sequence in question.”10)

This desubjectivization is acutely true of the video recordings by David and Jesse Friedman in Capturing the Friedmans. As filmmakers rather than as participants before the camera, they take on a desubjectivized form in the syntactical parallelisms they construct with the home movies of a decade or more before. The camera functions not as an omniscient observer or third person narrator, but reiterates the function of the home movie camera generally as participant and instigator in scenes, here, of camaraderie and high-jinks. These same images subsequently double-up to become part of the fantasmatique structured by Andrew Jarecki. In his case, psychic pleasure seems to stem from the construction of ambiguity about what happened in the past, what these social actors have said and done, and how they understand the actions of others as well as their own. Jarecki complicates the far more literal, linear and binary logic of the judicial system that sets out to determine “what really happened.” He reinscribes the ambiguity of perspective, and voice, that separates such judicial determinations from the plain of fantasy.

Guzman, too, in his reenactment of guarding the Presidential car inhabits the syntax of a sequence that he causes to flutter between past and present, that restores specificity (names, relationships) to the past and brings fantasmatic gratification to the present as he goes through the motions of reenacting the past to new ends. To me, this makes the subject’s presence, in reenactments, and documentaries more generally, a function of what I have described as the documentary voice of the filmmaker rather than his or her corporeal appearance before the camera. The documentary voice speaks through the body of the film: through editing, through subtle and strange juxtapositions, through music, lighting, composition, and mise en scene, through dialogue overheard and commentary delivered, through silence as well as speech, and through images as well as words.

The voice of an orator, or documentarian, enlists and reveals desires, lacks and longings. It charts a path through the stuff of the world that gives body to dreams and substance to principles. Speaking, giving voice to a view of the world, makes possible the necessary conditions of visibility to see things anew, to see, as if for the first time, what had, until now, escaped notice. This is not objective sight but seeing as a way of being “hit and struck,” caught in that precarious, fleeting moment of insight when a gestalt clicks into place and meanings arise from what had seemed to lack it or to be already filled to capacity with all the meaning it could bear.11) Such insight does not occur however, until given external shape, the shape provided by the film’s voice as it addresses others.12)

The documentary voice is the embodied speech of the historical person—the filmmaker, caught up in the syntax of reenacted images through which the past rejoins the present. Voice, given in reenactments partially as an awareness of the gap between that which was and that which now returns to what has been, also affirms the presence of a gap between an objectivity/subjectivity binary and a fantasmatique. Subjectivity suggests it is added to something and could also be subtracted. Voice is the means and “grain” with which we speak and can never be separated from what is said.

Objectivity desires a fixed relation to a determinate past, the type of relation that permits of “guilty/not guilty” verdicts or other definitive answers to the question of “what really happened.” Voice, in the form of reenactments that embody the “I know very well but all the same” formulation at the heart of psychic reality, imposes recognition of the relentless march of a temporality that makes the dream of a pure repetition and an omniscient perspective impossible. The very syntax of reenactments affirms the having-been-thereness of what can never, quite, be here again. Facts remain facts, their verification possible, but the iterative effort of going through the motions of reenacting them embues such facts with the lived stuff of immediate and situated experience.

Reenactments, also foil the desire to preserve the past in the amber of an omniscient wholeness, the comprehensive view we like to think we have that accounts for what came to pass without attaching this account to a distinct perspective. This can be the source of a sense of dissatisfaction: our view is too partial, too incomplete or too cluttered (it may contain a body or bodies too many as contemporary figures fill in for their historical counter-parts). Reenactments are clearly a view rather than the view from which to apprehend the past. They insist on the cumbersome limitations of an embodied perspective. Reenactments produce an iterability to that which belongs to the singularity of historical occurrence. They reconcile this apparent contradiction by acknowledging the adoption of a distinct perspective or point of view. Such perspectives can proliferate indefinitely but each of them can also intensify an awareness of the separation between the lost object and its reenactment. Reenactments belong to a situated fantasmatique that nullifies the status of that other fantasmatique of objectivity, omniscience and finality that haunts the documentary film.

Irene Lusztig’s film, Reconstruction, demonstrates the fragile veneer of objectivity that serves the interests of the state in her remarkable discovery of a reenactment of an extremely rare event: a bank robbery in Communist Romania. One of the robbers, it turns out, was Lusztig’s grandmother, the only person not executed for this crime against the people, or the people’s capital. Lusztig incorporates portions of the Romanian government’s reenactment of the crime, also called Reconstruction, which apparently sought to reaffirm the power of what was at that time a Communist state to write and control the past. In this case the fantasmatic quality of the reenactment pursues what is more clearly than usual an ideological issue: the at least temporarily lost object of state power. It seeks the gratification of staging a mise en scene within which that power can reconstitute itself. The robbers, once caught, were compelled to reenact their planning, the robbery, their confessions, trial and sentencing. They must once again go through the motions of their defiance of the state but, this time, without any anticipation of success.

The state’s film had apparently been intended to demonstrate the folly of breaking the law but it was never shown publicly for reasons that remain unclear. In it the suspects exhibit a decidedly despondent manner, a sign that they know the pleasure of this reenactment will not be theirs. Their eyes are vacant, their gaze unfocused, their words slow in coming and stilted in tone. In one scene, a prosecutor attempts to pry a confession from one of the men (Lusztig’s grandmother was the only woman involved). The suspect resists; he denies knowledge of the crime. Then the prosecutor produces hard evidence: the actual weapons used in the crime. The game is up and the suspect, with downcast eyes and the same hopeless tone, quickly admits his guilt: “You have those too? I see we’ve been discovered. Until now I’ve been hiding the truth”. With that, his confession begins.

This state sponsored reenactment introduces a sense of the ritualistic quality to reenactments of significant but past events. The robbery must be represented as a remarkable exception and the power of the state brought into play as another iteration in the eternal ritual of justice fulfilled. The capacity of this machinery to remain invulnerable requires the criminal participants in its reenactment to be shorn of defiance, calculation, and volition. Their own bodies serve as the surface for a textual rewriting in which agency reverts entirely to the state. This triumph of judicial invulnerability, however, unwittingly betrays the very condition of its being in the barely animated bodies of the criminals who must go through the motions of a past event in a context where need and pleasure, desire and gratification accrue only to the state. A “curse” continues to haunt the text but in the form of a disavowal that Lusztig, by recontextualizing the original reenactment from a distinct perspective of her own, exposes. Whereas reenactments may allow for an owning or owning up to the past, in Reconstruction the owning of the past takes the more literal form of the state coming into physical control, or ownership, of the bodies and minds of those who defied it.

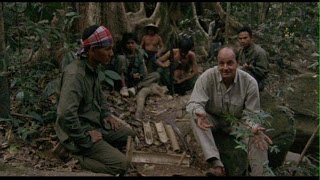

Reenactment takes another fascinating turn in Werner Herzog’s Little Dieter Needs to Fly. Shot down on a bombing run over Laos and captured, Dieter Dengler, after a series of extraordinary adventures, escapes his captors and returns to the United States. This is the story he tells to Herzog, but in the course of doing so he decides to reenact what he began to recount. Dengler and Herzog return to Laos where local villagers play his captors and Dieter plays his former self.

Little Dieter Needs to Fly (Werner Herzog, 1997)

Unlike the bank robbery reenactment in Reconstruction, the walrus hunt in Naook of the North, the reenactments of detention at Guantanamo in The Road to Guantanamo, or the “preenactments” of what might happen in the event of nuclear attack in Peter Watkins’ The War Game—all of which adopt the performative qualities of suspenseful, dramatic intensity—the reenacted scenes in Little Dieter exhibit a Brechtian sense of distanciation. In one scene, for example, the recruited villagers stand listlessly around Dengler, “going through the motions” of guarding him as their prisoner by wearing uniforms or displaying weapons. Their half-hearted, good-natured performance clearly conjures what Dengler went through without compelling prisoner or guards to reenter the psychic and emotional space of the original event. Neither Dieter nor Herzog seek to render suspense dramatically or verisimilitude perfectly. The necessary awareness of a gap between past event and present reenactment remains altogether vivid, as it gradually does in The Thin Blue Line where the series of reenactments of the original murder of a policeman construct an Escher-like impossible space of conflicting narratives.

Dieter transports himself back to that which now functions as a lost object through the social gests he puts into motion.13) It allows him to own his past in a corporeal but fantasmatic form that does not require the presumably therapeutic dramaturgy that Charcot inaugurated in his treatment of hysterics and that so many reenactments imitate. The sense of mastery that arises from this iteration in which the outcome is now known allows him to go through the motions of a triumphant passage already complete; it is this passage that the film within a film in Reconstruction denies to those whose bank robbery attempt failed. Dieter Dengler, the one who survived what once put survival in question, now occupies a fantasmatic mise en scene that affirms his very survival. “Going through the motions” takes on a formal, ritualistic quality that nonetheless spans the moment between before, when need prevailed, and after, when these social gests function as signifiers of what was but is now, at the moment of signification, past. The gests or signifiers both embody the lost object of a former experience and gratify the force of desire.

A similar form of reenactment occurs in the 1978 film, Two Laws, about aboriginal land rights in Australia.14) Divided into four parts, the first part introduces the main participants and then proceeds by a mixture of recounting, reenacting and reflecting on past events. The focal point is the arrest of several aboriginal people for the theft of a cow in 1933. One woman is beaten to death by a white constable during a forced march to the nearest jail. Although some events are recounted as the participants in the film reconstruct and relay the story to the younger members of the group, some are reenacted such as this beating. As with Dieter Dengler’s reenactment of his captivity in Laos no effort is made to render the event dramatically. Instead the constable swings a long club in slow motion toward the woman who plays the original victim without coming close to touching her. The entire action is filmed with a long shot that refuses the conventional découpage of cutting from a master shot to tighter, more highly charged shots to capture the violence in graphic form.

The reenactment has the distanciating quality of a Brechtian gest. No one is compelled to act out the original pain and trauma. Nor does the reenactment facilitate the work of mourning the past as much as the process of reclaiming it. The lost object remains lost but the social gest that replaces it restores it to a condition of visibility through a fantasmatic signifier that emerges from and embeds itself within the bodies of the participants. The duration of the moment between before and after hinges on this signifier that clearly stands for that to which it refers historically without any attempt to replicate that for which it stands, now, in the present. That there is a body too many is a crucial condition of the process in this case. The other, Australian law clashed with aboriginal law and, in 1933, won. Now, the reenactment of this event serves to give corporeal embodiment to what happened as those who remember it go through the motions that populate the mise of scene of their desire. A specter and a curse may haunt this space but it also serves as the site from which a desire for justice might achieve, in the future, the gratification that this event, from the past, set in motion.15)

These various reenactments begin to suggest some ways in which reenactments tend to cluster into different types. Some are highly affective, some far less so. Some make their status as reenactment obvious, some do not. These differences do not establish hard and fast divisions but do suggest different nodal points within a diffuse and overlapping universe of possibilities. Some particularly common variations include the following.

Nanook of the North (Robert Flaherty, 1922)

1. Realist Dramatization. The most contentious, because it is the least distinguishable from both that which it reenacts and the conventional representation of past events in fiction, be it in the form of a historical drama, docudrama, “true story,” or flashback, is the suspenseful, dramatic reenactment in a realist style. Nanook of the North may be the first recognized instance of this with the heightened tension of its will-he-or-won’t-he-succeed structure turning the hunt for salmon, walrus, and seals into high drama. These scenes reenact how hunting occurred in pre-contact Inuit culture, although this point is never made explicit. The status of the scenes as reenactments, as well as drama, remains shrouded, the better to intensify their affective dimension. That such a strategy can continue to prompt controversy is evident in the case of Mighty Times II mentioned earlier.

An important model for many recent reenactments of realist dramatization occurs in the powerful documentary, Las Madres de la Playa de Mayo. As one of the mothers who gather every day at the Argentine White House, La Casa Rosada, recounts how armed men abducted her son in the dead of night, the film cuts to a reenactment of this event. The reenactment possesses the surreal tones of a nightmare with its grainy, high contrast and slow motion imagery in which individual figures are unrecognizable. The distortions work to impede realist transparency. These formal devices shift the reenactment toward the fourth category here, the stylized reenactment, but Portillo’s and Muñoz’s expressive rendering of what happened stresses its emotional impact on the mother as something that was not part of the event itself but part of its affective reverberation ever since. Dramatization comes to a focus within the subjectivity of individual memory.

Night Mail (Harry Watt, Basil Wright, 1936)

2. Typifications. Problematic for similar reasons to realist dramatization is the reenactment of typifications. In this case there is no specific event to which the reenactment refers and the sense of separation between event and reenactment fades as a sense of typifying past patterns, rituals and routines increases. Such reenactments characterized many early documentaries, including Nanook of the North, where the suspenseful dramatization of events, presented as if they were present-day, reenacted the typical processes of the Inuit’s pre-contact past. The fur trapping and igloo building, for example, did not reenact specific historical occurrences as much as characteristic ones. To the extent that the viewer recognizes that the reenactment’s claim to authenticity resides not in their depiction of present-day activity, carried out despite the presence of the camera, but in the reenactment of pre-contact activity, staged for the sake of the camera, this very claim of authenticity undergoes erosion. The indexical quality of the image anchors it in the mise en scene of the filmmaker’s desire, as it does in fiction.

John Grierson, the commonly acknowledged father of the British documentary of the 1930s, adopted this technique wholesale. Reenactments, as typifications, proliferate. Coalface has several sequences of coal miners mining, or taking their lunch break, that possess an aura of present-day reality simply observed when they are, in fact, staged. Night Mail is the most famous example as postal workers sort mail, on a sound stage dressed to simulate the Postal Express as it makes its overnight journey from London to Glasgow. This scene reenacts, cites or reiterates the typical, and quotidian, quality of their labor. Like other films from this period and like their companion films from the Soviet Union such as Salt for Svanetia (Mikhail Kalatazov, 1930) or Enthusiasm: Symphony for the Don Basin (Dziga Vertov, 1931) the films exhibit a vivid desire to idealize the common working man as a vital part of a larger social whole.

Such scenes in Coal Face, Night Mail, Listen to Britain, Fires Were Started and other films function as “typical particulars” in precisely the way Vivian Sobchack applies this term to film. The specific actions and objects viewed in a fiction may be highly concrete as relayed by indexical images but they are not usually understood to have a concrete historical referent “…unless something happens to specifically particularize these existential entities as in some way singular…. “[Instead] they will be engaged as what philosophers call typical particulars—a form of generalization in which a single entity is taken as exemplary of an entire class.”16) This displacement from the singular to the exemplary, if recognized as such, forfeits some of the distinctive peculiarities of the documentary reenactment, most specifically the heightened sense of viewer responsiveness, and responsibility, that attends to the historical world.17) It reintroduces characteristics of narrative fiction into the documentary domain in a furtive manner. This reintroduction calls for a study of its own.

Far from Poland (Jill Godmilow, 1984)

3. Brechtian Distanciation. The reenactment of social gests (such as those in the pioneering Far from Poland but also abundantly evident in Little Dieter Needs to Fly and 2 Laws) greatly increases the separation of the reenactment from that specific historical moment which it reenacts, giving greater likelihood that the fantasmatic effect will come into play. The sense of a here and now couples to an awareness of a there and then so that the being-there-ness of the moving image and the having-been-there-ness of historical occurrence converge in the social gest. The gests of Dieter Dengler going through the motions of his captivity in a way that clearly reanimates its affective charge for him but without benefit of a full-blown realist dramatization allows the viewer to recognize the tangled temporality that has surrounded Dengler’s ever since. It is as if the very act of distanciation brings the spectral quality of the past into greater relief.

The Thin Blue Line (Errol Morris, 1988)

4. Stylization. Highly stylized reenactments such as those in The Thin Blue Line of Randall Adam’s interrogation or of the Dallas police officer’s murder, in which, most memorably, a perfectly lit container holding a malted milk shake tumbles through the night air in slow motion as if to blatantly over-dramatize one subject’s account, also achieve a sense of separation. This need not be in the ironic key so prevalent in Morris’s work. For example, His Mother’s Voice, an animated documentary from Australia, couples the radio interview of a bereaved mother as she is asked how she learned of her son’s shooting with an animated version of her journey to the house where her son had just been shot. These animated images sever any indexical linkage to the actual event but give voice to the acutely selective and pained perspective from which she experienced this tragic event. What is all the more remarkable in this mesmerizing film is that the sound track—her radio interview—repeats itself. As her account begins again the animation shifts in tone and quality and instead of taking us to the scene of the shooting it lingers within the family home, especially within the room of the now deceased son, as if to retrieve the memories that haunt this space. This highly stylized rendering of “what really happened” functions in a manner not unlike the abduction or disappearance reenacted in Las Madres de la Playa de Mayo. It carries the element of stylization even further. The viewer remains vividly suspended in that moment between before and after embodied in signifiers that possess an iconic rather than indexical relation to what has already happened.

I Am a Sex Addict (Caveh Zahedi, 2005)

5. Parody and Irony. Some reenactments adopt a parodic tone that may call the convention of the reenactment itself into question or treat a past occurrence in a comic light. Mockumentaries such as Forgotten Silver, about an early but fictitious pioneer filmmaker in 1900s New Zealand, often adopt this tack. Errol Morris skirts on the edges of this characteristic but his ironic perspective takes aim more at the subjectivity of his interview subjects than at the capacity of the reenactment to capture the authenticity of past events. Caveh Zahedi, on the other hand, adopts the parodic reenactment whole-heartedly in I Am a Sex Addict, a semi-serious account of his struggles with sex addiction and the confusion it wrecks on his longer-term relationships and attempts at marriage. At one point, speaking to the camera, he tells the viewer that he lacked money to go back to Paris to reenact his first encounters with prostitutes and so “this street” in San Francisco (the street on which he stands) will have to stand in for a Parisian street. The film cuts to another view and an evenly spaced line of about eight young prostitutes in front of a red brick wall as Caveh walks past, asking each of them the same questions about what they will do and how much they will charge, before hesitating, appearing ready to take them up on what they offer, but then deciding against it and going on to the next woman.

The Karen Carpenter Story, an underground cult favorite that cannot circulate legally because director Todd Haynes failed to secure permission for the sound track of songs by the Carpenters, tells the story of her eating disorders, dysfunctional family dynamics, addictions and ultimate death. Haynes does so by reenacting key scenes from her short life with Ken and Barbie dolls. For the most part these scenes have the quality of typical particulars, exemplifying pivotal moments without reference to historically singular events. The posed shots of dolls, however, add a powerfully ironic edge to the representations: as with His Mother’s Voice, this choice forfeits the impression of indexical authenticity in the image. At the same time it compels the viewer to assess this tragedy as something both beyond the reach of any reenactment and as something typically reduced to a cautionary tale about the perils of anorexia and bulimia. The parodic edge puts the mass media’s penchant for the realist dramatization of tragedy on display as a potentially exploitative trope. The doll figures, by maintaining a clear separation between reenactment and prior event, may actually mobilize a more complex form of understanding of what this tragedy actually entails than more straightforward representations that confuse the boundary between the two.

Similar points might be made about The Eternal Frame, the Ant Farm collective’s parodic reenactment of the Kennedy assassination. This video documents the reenactment and the behind the scenes preparations that went into it far more than it purports to be a documentary about the assassination itself. Unlike JFK, which attempts to fit the black hole of what really happened into the round peg of a definitive explanation, The Eternal Frame calls the very act of reenactment into question. By exaggerating the separation between then and now, before and after, this work functions to bare the device of reenactment itself rather than rely upon this peculiar form to achieve any final answer to the question of what really happened or generate a mise en scene in which the desire for a lost object might find a gratification.

His Mother’s Voice (Denis Tupicoff, 1997)

Reenactments within these clusters of overlapping and fuzzy categories do not do what archival footage and other images of illustration do.18) They do not provide evidentiary images of situations and events in the historical world. If they allow viewers to think that they do, they lay the groundwork for feelings of deception. The indexical bond, which can guarantee evidentiary status—but not the meaning or interpretation of images taken as evidence—no longer joins the reenactment to that which it stands for. This bond joins the image to the production of the reenactment: it is evidence of an iterative gesture but not evidence of that for which the reenactment stands. It is, in fact, an interpretation itself, always offered from a distinct perspective and always carrying, embedded within it, evidence of the voice of the filmmaker.

Reenactments do not contribute inartistic proofs, in Aristotle’s description of rhetoric, but artistic ones. Not evidence but invention. Although it is possible, especially with realist dramatizations and typifications, to think that they do contribute evidence, what they actually contribute is persuasiveness. They fulfill an affective function. For documentaries belonging to the rhetorical tradition, reenactments intensify the degree to which a given argument or perspective appears compelling, contributing to the work’s emotional appeal, or convincing, contributing to its rational appeal by means of real or apparent proof.

As pathos or logos, reenactments enhance or amplify affective engagement. Reenactments contribute to a vivification of that for which they stand. They make what it feels like to occupy a certain situation, to perform a certain action, to adopt a particular perspective visible and more vivid. Vivification is neither evidence nor explanation. It is, though, a form of interpretation, an inflection that resurrects the past to reanimate it with the force of a desire. They provide a key element of the mise en scene within which a documentary fantasmatic takes shape.

Reenactments effect a fold in time. They vivify the sense of temporal duration that extends from here to there, now to then. Lived experience thickens and twines about itself. They take past time and make it present. They take present time and fold it over onto the past. They resurrect a sense of a previous moment that is now seen through a fold that incorporates the embodied perspective of the filmmaker and the emotional investment of the viewer. In this way reenactments effect a temporal vivification in which past and present co-exist in the impossible space of une phantasmatique. Reenactments stand for something different from that for which they stand would stand. This difference manifests itself in the resurrected ghosts that both haunt and endow the present with psychic intensity. Reenactments, like other poetic and rhetorical tropes, bring desire itself into being. They activate the fantasmatic domain wherein the temporal duration of lived experience and the efficacy of ideology find embodiment.

Filmography

Capturing the Friedmans (Andrew Jarecki, 2003)

Chile, Obstinate Memory (Patrizio Guzmán, 1999)

Coalface (Alberto Cavalcanti, 1935)

The Eternal Frame (T. R. Uthco and Ant Farm Collective: Doug Hall, Chip Lord, Doug Michels, and Jody Proctor, 1975)

Far from Poland (Jill Godmilow, 1984)

Fires Were Started (Humphrey Jennings, 1943)

Grizzly Man (Werner Herzog, 2005)

His Mother’s Voice (Denis Tupicoff, 1997)

I Am a Sex Addict (Caveh Zahedi, 2005)

JFK (Oliver Stone, 1991)

Las Madres de la Playa de Mayo (Susana Blaustein Muñoz, Lourdes Portillo, 1985)

Listen to Britain (Humphrey Jennings, Stewart McAllister, 1942)

Little Dieter Needs to Fly (Werner Herzog, 1997)

Lonely Boy (Wolf Koenig, Roman Kroitor, 1962)

Mighty Times: The Children’s March (Robert Houston, 2004)

Nanook of the North (Robert Flaherty, 1922)

Night Mail (Harry Watt and Basil Wright, 1936)

Reconstruction (Irene Lusztig, 2002)

The Road to Guantanamo (Michael Winterbottom and Mat Whitecross, 2006)

The Thin Blue Line (Errol Morris, 1988)

Two Laws (Carolyn Strachan and Alessandro Cavadini, 1982)

The War Game (Peter Watkins, 1965)

Notes

1) This formulation derives from Gregory Bateson’s insightful essay on the difference between play and fighting among animals where a nip no longer means exactly what a bite, to which it refers, would mean: “The playful nip denotes the bite, but it does not denote what would be denoted by the bite.” “A Theory of Play and Fantasy,” Steps to an Ecology of Mind (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000). The distinction is akin to Gilbert Ryle’s discussion of the difference between an unintended blink and a fully intended wink in “The Thinking of Thoughts: What is ‘Le Penseur” Doing?” University Lectures, No. 18 (University of Saskatchewan, 1968).

2) I am deeply indebted to Terry Castle’s essay “Contagious Folly: An Adventure and Its Skeptics,” in a special section of Critical Inquiry, Vol. 17, no. 4 (Summer 1991): 741-772, devoted to “Questions of Evidence” in which she makes clear the imbricated relationship between a particular folie a deux and the work of ideology.

3) The formulation derives from Louis Althusser’s essay, “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses,” in Lenin and Philosophy (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1971. The emphasis here is on the subject’s psychical investment in a given state of affairs rather than on the idea of ideology-in-general as that which constitutes the subject. Though related, the latter point leads to numerous questions about the degree to which such a subject is essentially determined by and subject to the work of ideological apparatuses. However that question is answered, the centrality of a psychical investment is what provides a linkage between ideology and a fantasmatic.

4) Jean Laplanche and J.-B. Pontalis, The Language of Pscyho-Analysis (New York: W.W. Norton, 1973): p. 317.

5) Jean Laplanche and J.-B. Pontalis, “Fantasy and the Origins of Sexuality,” The International Journal of Pscyho-Analysis, Vol. 49, Part 1 (1968): p. 16. The essay also appears in a booklet that reprints the original essay first published in Les Temps modernes in 1964: Fantasme originaire, Fantasme des origins, Origines du fantasme (Paris: Hachette, 1985).

6) Laplanche and Pontalis, “Fantasy and the Origins of Sexuality,” p. 15.

7) Laplanche and Pontalis, “Fantasy and the Origins of Sexuality,” p. 15.

8) Laplanche and Pontalis, “Fantasy and the Origins of Sexuality,” p. 15, fn 36.

9) Laplanche and Pontalis, “Fantasy and the Origins of Sexuality,” p. 16.

10) Laplanche and Pontalis, “Fantasy and the Origins of Sexuality,” p. 17.

11) “In great moments of cinema you are hit and struck by some sort of enlightenment, by something that illuminates you, that’s a deep form of truth, and I call it ecstatic truth, the ecstasy of truth, and that’s what I’m after in documentaries and feature films.” Werner Herzog, “Fresh Air,” NPR radio, July 28, 2005.

12) Some speak of subjectivity in documentary. This, to me, represents something of a slippery slope, slipperier than the use of subjectivity in narrative fiction which is usually related to the perspective of characters and the voice of the narrator. Both are different concepts from documentary subjectivity that sets out to admit that documentaries represent situated, emotionally and politically informed views of the world. Though true, they become inevitably contrasted with an alternative idea, a different way of representing or engaging with the world, objectivity. The issue of objectivity enters, like a Trojan Horse, in ways it does not do in fiction and it causes endless trouble.

Objectivity in relation to a fictional world might seem a peculiar notion since the fiction is a subjectively endowed creation by definition, or it may seem like a way to identify a scrupulously neutral, detached mode of representing it, in the spirit of écriture blanche, a zero degree of style. In documentary, objectivity implies a lack or subtraction of subjectivity as if subjectivity cold be put on, taken off or stepped beyond, as if it were a bias. Unlike a fiction, the actual world, it is argued, can be viewed objectively, unless the decision is made to “add” subjectivity. In some instances, like scientific investigation, subjectivity can be subtracted to a great extent but these instances are not the instances in which an I stands before a You; they are instances of I’s embedded within institutional procedures and discourses that objectify or analyze, that have instrumental effects—for good or ill—but that cloak the I or You in ways the voices of these films refuse to do. Voice affirms the presence of an embodied subject who is necessarily and inescapably in possession of a subjectivity. Objectivity catapults us into another realm entirely.

13) Brecht regarded social gests as physical actions that revealed social relations or as Roland Barthes put it, “What then is a social gest? It is a gesture or set of gestures (but never a gesticulation) in which a whole social situation can be read. Not every gest is social: there is nothing social in the movements a man makes in order to brush off a fly; but if this same man, poorly dressed, is struggling against guard-dogs, the gest becomes social.” “Diderot, Brecht, Eisenstein,” Image, Music, Text (New York: Hill and Wang, 1977): 73-74.

14) Originally shot in 16mm film in 1978, the filmmakers resisted transferring it to video or laserdisc because of concern for the resulting quality of the image. Facets Video is now in the process of releasing a freshly prepared DVD version of the film, with additional commentary and new scenes bringing the original struggle to recover tribal lands up to date.

15) In 2006 a court victory allowed the Aboriginal people to reclaim several islands off the shore of north-central Australia as tribal lands.

16) Vivian Sobchack, Carnal Thoughts: Embodiment and Moving Image Culture (Berkeley, University of California Press, 2004): 281.

17) Sobchack develops this point on p. 283 in relation to fiction film and moments when the image ceases to function as a typical particular and takes on the full force of a singular moment, such as the image of a real rabbit shot during the fictional hunting scene in The Rules of the Game. This attitude seems a default value for documentary film in general.

18) Images of illustration comprise those images utilized to support a typically verbal argument or perspective. They offer particular instanciations of points that may imply broader application or offer what appears to be evidence in support of a specific assertion.