Collective Mind

Film collectives are transforming the language of cinema, the concept of authorship, and the boundaries of political imagination. This year's Ji.hlava International Documentary Film Festival presents a selection of collective works from the 1950s to the present day, across Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Americas.

Exceptional narrations and imaginative styles are typically associated with individual auteurs in cinematography. Although film is, by its nature, a collective work, the source of aesthetic inventiveness or conceptuality is usually the director’s personality. Film collectives transcend this notion, and some of them, both historically and in the present day, have shown that even a non-hierarchical community of people who provide the necessary professions for the creation of a film can produce works that are thematically strong and, at the same time, aesthetically sophisticated, engaging, and innovative.

The Collective Film retrospective presents examples of film collectives from different periods and continents. The motivations for their establishment were diverse – ranging from production reasons and the need to share resources, to a shared vision of what film should serve, and how, to the conviction that film, as a product of the collective mind, can speak to the audience in a language and with an emphasis that is stronger than individual statements, more analytical than contemporary media messages, smarter than the outcries of individuals, and more authentic than a single view of complex events.

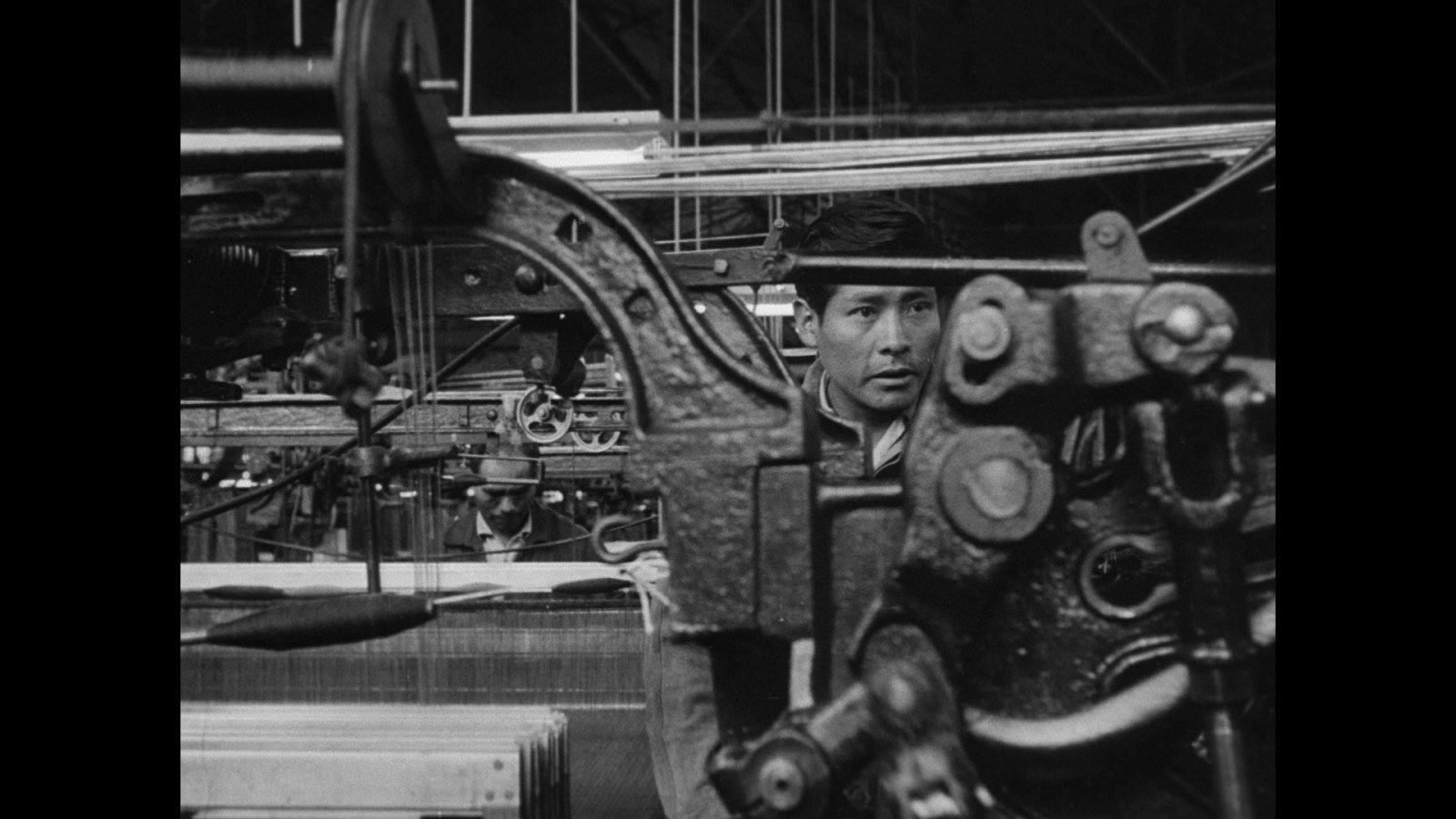

The Bolivian collective UKAMAU Group was founded in 1966 to defend the rights of the indigenous population. The main imperative of their work was to film in collaboration with the communities about which the film told. In the retrospective, Blood of the Condor (1969) will be screened. This hybrid film combines the approaches of fiction and documentary. The interweaving of documentary observation and staged scenes featuring the indigenous population is one of the creative methods that made it possible to capture even elusive situations that were nevertheless key to understanding the problem. Blood of the Condor reconstructs the sterilisation of indigenous women by representatives of American peace corps.

The African collective Laboratoire Agit Art was founded in Senegal. This multidisciplinary artistic collective was established in 1974 by artist Issa Samb, filmmaker Djibril Diop Mambéty, painter El Hadji Sy, and playwright Youssoupha Dione. It addressed social and political issues, primarily through polemics with the philosophy of négritude. Its unstructured nature also meant total openness: there was no definitive answer as to who ‘belonged’ to the collective and who did not. The documentary Joe Ouakam (2012), which is part of the retrospective, was filmed by Mambéty’s brother, Senegalese musician, composer, and singer Wasis Diop, and is a spontaneous observation of Ouakam’s thoughts during his walks through Dakar. The collective created documentary and feature films, video installations, and the interactive film Si Poterris Narrare (2002).

The African collective Laboratoire Agit Art was founded in Senegal. This multidisciplinary artistic collective was established in 1974 by artist Issa Samb, filmmaker Djibril Diop Mambéty, painter El Hadji Sy, and playwright Youssoupha Dione. It addressed social and political issues, primarily through polemics with the philosophy of négritude. Its unstructured nature also meant total openness: there was no definitive answer as to who ‘belonged’ to the collective and who did not. The documentary Joe Ouakam (2012), which is part of the retrospective, was filmed by Mambéty’s brother, Senegalese musician, composer, and singer Wasis Diop, and is a spontaneous observation of Ouakam’s thoughts during his walks through Dakar. The collective created documentary and feature films, video installations, and the interactive film Si Poterris Narrare (2002).

Asian collectives are represented in the retrospective by the Indian Raqs Media Collective, founded in 1992. It focuses on visual arts, especially installations and sculptures, and creates films, videos, performances, and texts. The essay The Blood of Stars (2017) is a philosophical treatise that draws on metaphors from geology and biology, focusing on reflections on wealth, war, and the exploitation of natural resources.

Two British collectives, Sankofa and Black Audio Film Collective, made significant contributions to 20th-century European art. Sankofa Film & Video Collective was founded in London in 1983. Its founding members were Isaac Julien, Nadine Marsh-Edwards, Maureen Blackwood, Martina Attille, and Robert Crusz – British students from families who had come to Britain from Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean. The postcolonial experience was the starting point for other social and political issues that the collective focused on in its work. Questions of identity and sexuality also arise. The film Inbetween (1992) is a gentle, poetic testimony to identity caught between East and West. It is an example of films that captured personal and intimate perspectives, but also addressed broader political issues. The Black Audio Film Collective also addressed the experience of perceived difference, and its personal and social consequences.

Two British collectives, Sankofa and Black Audio Film Collective, made significant contributions to 20th-century European art. Sankofa Film & Video Collective was founded in London in 1983. Its founding members were Isaac Julien, Nadine Marsh-Edwards, Maureen Blackwood, Martina Attille, and Robert Crusz – British students from families who had come to Britain from Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean. The postcolonial experience was the starting point for other social and political issues that the collective focused on in its work. Questions of identity and sexuality also arise. The film Inbetween (1992) is a gentle, poetic testimony to identity caught between East and West. It is an example of films that captured personal and intimate perspectives, but also addressed broader political issues. The Black Audio Film Collective also addressed the experience of perceived difference, and its personal and social consequences.

In 1967, a total of 60 underground filmmakers and student activists who were dissatisfied with the media’s portrayal of the March on the Pentagon, a mass demonstration against the Vietnam War, gathered in New York. They discussed how to find and combine their resources to create a ‘counter-documentary’ that would truthfully portray the event. This led to the creation of the Newsreel collective. Their films often do not feature individual names in the credits – members took turns in various professions, working on the film, and attributed the output to a collective identity.

Over time, regional branches of the collective were established in San Francisco, Boston, Los Angeles, Detroit, Chicago, and Atlanta. The original Newsreel consisted mainly of men, but by the early 1970s, non-white members and women predominated. When distributing films, they placed importance on discussions after the screening. They typically screened films outside of cinemas, in collaboration with various political and human rights organisations. In the 1960s, there were several dozen film and art collectives in the United States. Alongside Newsreel, Videofreex was among the first. In the early 1970s, it moved to a community farm, where it founded the first pirate television station in the United States (Lanesville TV), and a media education centre.

The retrospective opens with Isidore Isou’s Lettrist film Venom and Eternity. In this case, it is not a collective film in the sense described above. The Lettrists were a French group of artists who shared aesthetic values and the belief that art needed to be reinvented around a basic unit – the letter. It was founded after the end of the Second World War by Isou and Gabriel Pomerande. Their main areas of activity were poetry, painting, film, and philosophy, but one wing of the Lettrists also devoted itself to political theory. The works were attributed to individual authors, albeit always in the name of shared beliefs. The Lettrists can therefore be seen as a kind of transition between the artistic movements of the interwar avant-garde and the artistic collectives whose firm place in the history of cinema and the visual arts began in the 1960s.

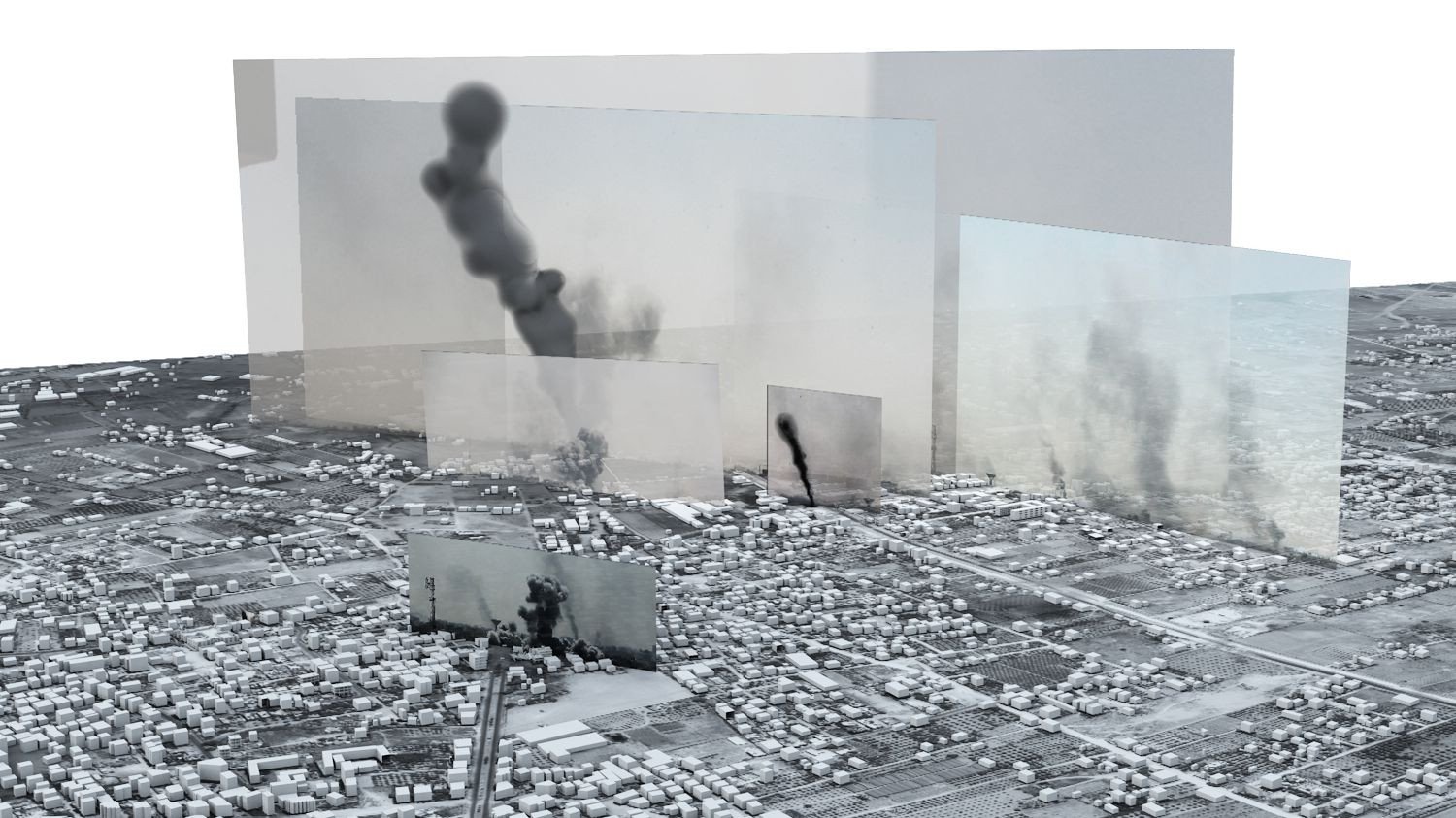

The newest collective in the retrospective is the expert group Forensic Architecture. It brings together scientists and experts from various disciplines. By combining scientific methodologies and expert knowledge, it works to reconstruct events that could not be monitored at the time or immediately afterwards by journalists or independent institutions focused on law or human rights. This is how The bombing of Rafah in Palestine was reconstructed, which will be screened as part of the retrospective. Forensic Architecture will present their masterclass, where they will introduce their working methods, along with their scientific and creative approaches.