Biopics and the Trembling Ethics of the Real

Timothy Corrigan (1951) is among the most prominent minds in film today. He teaches at the University of Pennsylvania, and on American soil he has long been developing subjects which could be considered continental European. He engages in a two-way reflection of film and literature through the theory and history of film essayism, the analysis and typology of the film experience, and the interpretation of New German Film. In fall 2019 Corrigan came to the Czech Republic at the invitation of the Ji.hlava International Documentary Film Festival, where he participated as a juror for the competitive section Between the Seas. He presented his essay “Biopics and the Trembling Ethics of the Real” as a part of his lecture for students in the festival’s educational module Media and Documentary. Here we publish the essay by Timothy Corrigan and the introduction to this essay by Czech theorist Tereza Hadravová.

--

Introduction

Within the context of contemporary Czech film theory, it seems like the most interesting of the approaches Timothy Corrigan proposes for film research: to consider film as an adaptation of the real. This view, as the author indicates in his introduction, can be applied to the whole of cinematography. In this thought we can hear the echo of so-called contemporary film theory,1) which understands the relationship between film and reality not as a prism through which to view a kind of neutral depiction of external reality, but rather as a means of enforcing and strengthening – or on the contrary subversively exposing and dismantling – the hidden rules of the reigning ideology. After all, Corrigan did spend a formative year in Paris, where he studied under Christian Metz.

Contemporary film theory, contrary to its name, is seen today in English language film theory circles as an outdated or even discredited theory.2) And although Corrigan doesn’t engage in a direct debate with the cognitivists or neoformalists, who most often held a critical stances toward contemporary film theory, his work represents a bold attempt, led simultaneously on several fronts, to continue, modernise, and publicise the necessity of contemporary film theory in these cinematographic, technological, and social conditions.

In this essay Corrigan distinguishes reality from the real. He labels reality as something that gets its status against the backdrop of a particular social structure and in the wake of a concrete historical situation. Our recognition of something’s status as reality is contingent on an act which is complicated, deeply embedded in history and culture, and usually unconscious. The fabricated character of reality can best be seen in moments of so-called paradigm shift or in situations we have all experienced: when met with the divergent reality of another person. The real, on the other hand, is the fundamental basis for all possible versions of reality. In itself, it is unreachable: it exists as pure potentiality.

Corrigan considers films to be adaptations of reality. A film is then either a means of enforcing a particular version of reality or it can instead become a tool of subversion and an attempt to replace it with a different version. But Corrigan adds yet a third type of cinematographic engagement with the real: (self-)reflexive films, which ultimately concentrate on the very process of construing reality through film, narrative, imagery, or memory. In Corrigan’s view it’s these films that manage to indirectly touch the real itself.

In his essay Corrigan applies this to a subgenre of documentary filmmaking – (auto)biographical films (biopics) – in which this briefly described mechanism of adapting reality is easier to grasp. Both the first and second types of documentary can be labeled conventional: their task is to enforce a particular adaptation of reality. This obviously applies not only to propaganda and (supposedly) neutral educational films, but also to critical, subversive documentaries – because in a certain regard it doesn’t matter whether the asserted reality is the “official” one or a disparate alternative. This is why in his essay Corrigan describes “conventional” documentaries as those in which the subjects “measure and determine the real” by using a fundamental filter that can attempt to display or highlight the often ignored or unorthodox face of a real historic event.

However, in this study Corrigan more is interested in different types of (auto)biopics – those which intentionally problematise narrative authenticity and the identity of the narrating subjects, who “unmoor memories across the challenge of evidence.” He asserts that documentary reenactments are the preferred technique of these films (he refers to, among others, a study by Bill Nichols, which is also available in the theory section of dok.revue). This type of cinematography relates differently to reality than a conventional documentary: it is not about the competition between versions of reality, of which only one is true, but rather about coming closer to the fountainhead of all realities in a place of pure possibility, which Corrigan, using the lexicon and conceptual imagery of Giorgio Agamben and Jean-Luc Nancy, describes as a “zone of indistinguishability” or a “world shaken, trembling, as the winds blow through.”.

Tereza Hadravová

Introduction translated by Brian D. Vondrak.

Notes

1) Contemporary film theory is a designation that caught on in English language publications dedicated to the French film theorists of the 1970s who utilised semiotics, psychoanalysis, and (neo-)Marxism in their study of film, for example Jean-Louis Baudry and Christian Metz. It is also used as a label for the work of English and American theorists such as Stephen Heat and Colin MacCabe, who followed in the footsteps of these French theorists.

2) The works of Noël Carroll and David Bordwell are seen as the beginning of the end. See, for example: Noël Carroll. Mystifying Movies: Fads and Fallacies in Contemporary Film Theory. New York: Columbia University Press, 1988; David Bordwell and Noël Carroll (eds.). Post-Theory. Reconstructing Film Studies. Wisconsin (MA): The University of Wisconsin Press, 1996.

Biopics and the Trembling Ethics of the Real

Timothy Corrigan

Let’s begin by noting the obvious: that the real is not reality, and the tension between them is often the most productive part of a film and our engagment with it. Most broadly all films might be said to be explicitly or implicitly engaged with adapting reality as an attempt to define or categorize the real in different ways. Whether we regard cinematic representation as an indexical, semiotic, or some other system, since 1895, movies have performed this adaptive action to frame reality, among other shapes, as an epistemological fact, a philosophical concept, a psychological state, an aesthetic category, a cultural situation, an ideologocial position, a personal expression, or a historical event—all portentially different versions of a real. Certain films clearly emphasize one or another of these frameworks to underpin a specific reality principle for understanding the real. Others overlap and mix these registers as a way of foregrounding and complicating the very notion of the real. Thus, as an extremely complex example, Vertigo (Hitchcock, 1958) might be said to explore and represent the layers of an ever elusive reality as it spins through different spaces of the real, creating a continually regressing mise-en-abyme that contains the metaphysical, the psychological, the sexual, and the legal real.

For me, the question of what counts as “the real”—and the variety of cinematic responses to it—becomes invariably informed by the search for cinematic value. Put simply, to adapt a real is invariably an act of valorizing where the real lies. Dramatizing and problemitizing the movement and tension within the adaptation of the real thus foregrounds a central question about ethics and value within adaptation itself—as both a questioning and securing of its assumptions and faith in the power to adapt and appropriate reality as the real. With touchstones in the work of Giorgio Agamben and Jean-Luc Nancy, here I want to look at two recent and extraordinary auto/bio pics—The Missing Picture (Pahn, 2013) and Stories We Tell (Polley, 2012)—to see how these films investigate and complicate the real and, in the process, valorize specific relationships to it. Whereas more conventional adaptations often appear to promote an ethics of the real as what I’ll call self-evident, these films explore the difficult terrain of demarcating the real across the shifting and unstable grounds of uncertain evidence. The word “trembling” in my title comes from Jean-Luc Nancy and I emphasize it to mark this other encounter with the real—in its most provocative and creative state—as something that is there but not there, as evidence that resists adaptation. At the heart of the adaptation of evidence rather than self-evidence, the key strategy becomes reenactments which provoke two actions 1) a desubjectivization of the world and the self which in turn 2) releases the real into the domain of phantoms.

L’image manquante

Adapting Realities

With a more restricted and focused defintion of adaptation, the drama of adapting the real becomes commmonly a matter of transposing, uncovering, translating, mediating (or any number of adaptative metaphors commonly used in adaptation studies) source material from one medium to another. These are well-worn questions: Is the adaptation true to the spirit of Shakespeare or Austen? Does the cinematic character adequately embody the literary character? Are themes maintained? Are stylistic elements creatively but accurately reconfigured? More interestingly, if the adapting text strays significantly from the source, has the adaptation convincingly created an alternative real? The recent Anna Karenina (Wright, 2012), for instance, reclaims the real of its source novel through a relatively extreme stylistic transformation that identifies and refashions the reality of the novel as a sexual theatrics, an interpretation which condenses and higlights the cumbersome reality of the novel. Indeed, with these literary adaptations,that vague and indeterminant zone where a “real” moves is explicitly signalled in the different phrases that gesture towards it as “based on,” “inspired by,” and “adapted from.”

Perhaps closer to and more obviously embedded in the core of the matter, documentary films can be described most directly as adaptations of reality as a certain figuratiton of the real. Since the 1920s and Grierson’s definition of a documentary as the “creative treatment of actuality” to the explosions of contemporary documentaries as personal, essaysitic, animated, and interactive, documentary practices have claimed to circumvent and adapt reality as objective, orchestrated, political, immediate, digital, three dimensional, and unrepresentable. In the last twenty years especially—partly because of the so-called digital turn in contemporary cultures—these questions have grown especially prominent, vexed, and contentious. Today especially, the real—as spread across our vast media landscapes—has become a turbulent, exciting, and sometimes silly field of different practices (ranging from digital ethnographies to reality shows) in which the status of the real is continually adapted, redefined, and debated.

Indeed let me here refocus this field of documentary adaptations even more specifically on biographical or autobiographical films, since both practices are especially rich terrain for questions about subjectivity, adaptation, and their relation to the real, questions which foreground issues about the value and ethics of adaptation. Implicitly or explicitly these films describe human agency in the world and the extent to which that agency can circumscribe and define the reality of that world through the movement, expressions, desires, and gestures of its subject. In these cases, the human subject typically anchors, discovers, or acts as guide for the subjective terms of the real. The perspectives and actions of the individual become the assumed agency for discovering and presenting the key truths as evidence in a social or natural world. Focused on a real historical identity, these agents of the real create and reflect their worlds as a kind of knowledge and value. For example, films such as Rob Epstein’s The Life and Times of Harvey Milk (1984) or Nanni Moretti’s Dear Diary (Caro Diario, 1993) map very different worlds through different agenices whose personal tragedy or personal tragi-comedy imbue those worlds with specific ethical values about sexual politics in one case and psychosocial, aesthetic, and physical resiliency in the other. Conventional biographical and autobiographical subjects ultimately measure and determine the real as a particular value produced by knowledge, emotion, and memory across the activity that filters reality. Less conventional biopics or auto-biopics, however, might reflexively dramatize that action and agency in order to open it to an ethics of potential and possibility. In these cases, especially, reenactments become the center of a complex shifting between adapting reality and the real, between what I will describe as decreating and recreating evidence of the real.

Evidence and Ethics

To open up these questions in a somewhat provocative way, I am going to do what true philosophers often decry: cherry-pick ideas from the work of Agamben and Nancy as part of a shorthand to rethinking the problematic of adapting the real. More exactly, I want to borrow some of their positions to create a critically reflexive model whereby adapting the real can mean inevitably gesturing towards it in a way that defines it as always inaccessible and resistant to the look of adaptation. In these cases, in short, adaptation points to a real it cannot truly represent.

L’image manquante

I am particularly interested in Nancy’s suggestions in his book The Evidence of Film—his reflections on the films of Abbas Kiarostami—where the real resides “in leaving things unclosed.”3) This central evidence that film mobilizes thus identifies “a blind spot” that opens that cinematic gaze and “presses upon it to look” at what it may be unable to see.4) This is a cinema of “eye openers,” Nancy claims, where the real resists, precisely, “being absorbed in any vision” and where “a world refers only to itself.”5) This more radical real opens to “an increased plurality,” revealing its “essentially multiple essence” through cinema’s “internal multiplicity” of “pictures, image as such, music, words and finally movement.”6) Here a film “ceaselessly moves, so to speak, in the film or out of the film in order to reenter it.”7) Here discovering the real becomes, significantly I think, a kind of education, based on the etymology of the word education is “to bring out” the real of the world: “The evidence of the cinema is that of the existence of a look through which a world can give back to itself its own real and the truth of its enigma . . . , a world moving of its own motion, without a heaven or a wrapping, without fixed moorings or suspension, a world shaken, trembling, as the winds blow through it.”8)

Dovetailing with Nancy’s notions about cinema and the real are Agamben’s arguments about “gesture” and two terms related to his conception of gestural montage: repetition and stoppage. For Agamben, gesture implies “the exhibition of mediality as well as “the process of making a means visible as such,” so that in the world of images, “gesture is the point of flight from aesthetics into ethics and politics” in the world.9) Here gesture describes the “decreation of the real,” or decreation of facts as part of a larger desubjectivization of reality. In Jean-Luc Godard’s work, for instance, Agamben tells us that gesture “functions as an unveiling of the cinema by the cinema,” which takes us to the realm of mediality where adaptation thrives in the intersection of adaptive encounters.10) Gesture in the broadest sense of the term calls forth the interstices in the act of adapting the real so that “repetition and stoppage” become the salient vehicles for revealing a world beyond the image as potential and possibility: “repetition is not the return of the same but the return of the possibility of what was”; it “realizes the messianic task of cinema” to create “an image of nothing” that no longer recounts meaning and thus returns the real to the ethical potential of new meanings and new possibilities.11) The ethics and value of reality are thus a possibility and potential: a “zone of indistinguishability” or, in Agamben’s phrase, “bare life.”

Reshaping these remarks, I am interested in how cinematic adaptations gesture towards the real as this zone of “bare life” in the realm of possiblity. Conventional adaptations of real events and people usually mold and defer this zone in order to redirect value to the illusion of representational authenticity, coherent identities and subjectivities, and the closure of memory so that the ethical challenge of the real is foreclosed as the self-evident. The documentary biographies and autobiographies I address here instead openly undermine representational authenticities, trouble their identities, and unmoor memories across the challenge of evidence and the action of reenactment as adaptation.

L’image manquante

Bill Nichols and Ivone Margulies are two of a growing number of scholars who recognized this strategy of reenactments as one of the richest and most suggestive directions in contemporary documentaries. As Nichols characterizes reenactments, they intiate a “desubjectivization” of the subject in “a gap between the objectivity/subjectivity binary and the workings of the fantasmatic.”12) Here, “Facts remain facts,” as he points out,“but the iterative effort of going through the motions of reenacting them imbues such facts with the lived stuff of immediate and situated experience.”13) Taking a different tack, Margulies aligns reenactments with ethics where the repetitious exemplarity of reenactments “converts” the spectator because they produce “an improved version of the event” as a “modern morality tales”: “Inflected by a psychodramatic (or liturgical) belief in the enlightening effects of literal repetition, reenactment creates, performatively speaking, another body, place, and time. At stake is an identity that can recall the original event (through a second-degree indexicality) but in doing so can also re-form it.”14)

Decreating and Recreating Real Identities

I want now to refocus the relationship between the kinds of agencies explored in these documentary adaptations and the worlds they map. I will be schematic and look at two distinctive versions of these kinds of films, The Missing Picture and Stories We Tell. In these two instances, we witness historical agencies for engaging versions of the real specifically as a process of decreating the real and recreating it, after Agamben, as an open “zone of indistinguishability.” Whereas adapting the world as a self-evident real reflects mainly that self rather than the world, these films explore the elusive evidence of a world as a pressure on the agency of that self, mapping the territory where a real becomes visible through Agamben’s notions of stoppage and repetition, and foregrounded especially through reenactments.

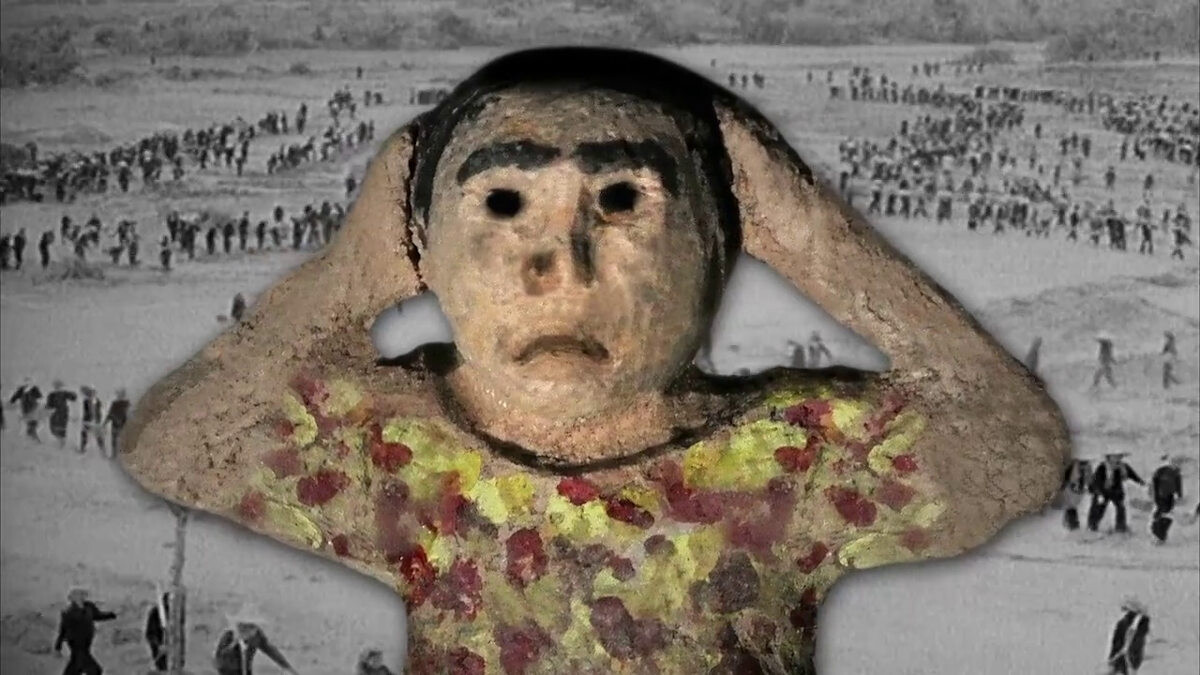

In Cambodian filmmaker Rithy Panh’s 2013 autobiographical account of the Khmer Rouge genocide from 1975-1979, the real is blocked, stopped in its track by the imponderabily of the violence of that genocide and the erasure of virtually all evidence and representations of that violence. During the four years of this Cambodian holocaust virtually all the vestiges of a pre-revolutionary society were eradicated by mass murder, mass torture, and mass imprisonment, with most representational evidence of these atrocities destroyed by Pol Pot’s revolutionary soldiers. As the film and Phan’s voice-over reflect on the death of his family, they meditate on the incomprehensible loss, while they concomitantly work to document a horrific reality whose only remaining representational records have been emptied of truth, or more exactly whose real truth is its emptiness—like the images of the city of Phnom Penh, emptied of people and marked only by deserted buildings.

Pahn explains the film’s titular argument, in a post-release interview, as a particular provocation that generated the larger investigation of the film: one of the Khmer Rouge “photographers said he had shot some images of an execution. But I was never able to find them—maybe somebody hid them somewhere or they are being kept underground. The search for that image became important to me—as a record. This was the first ‘missing picture.’ I also asked myself whether an image can ever really tell the truth. An image is not the truth—even if it’s taken from a final act like an execution—it can not tell the full truth. Part of the picture will always be missing. . . . [Later] the idea for the film completely changed. The missing picture took on more meanings—of the Khmer Rouge execution, of a family universe that no longer exists in this world, and more.”15)

In search of this fundamental loss and vanishing, the film proceeds as a series of remembrances of Pahn’s life as a child with his family (in a home that is now a brothel) and his years in a prison camp where death and brutality permeated his daily experience. As Pahn’s struggles, in voice-over, to remember a life that has disapeared, memories return in the film as fragile and stationary puppet shows in rickety buildings with toy-like inhabitants. Since the real here is always a missing image, the attempt to locate that real means to “decreate” the image itself by inhabiting it with painted clay recreations of people as unanimated figurines and events as unanimated arrangements of these figurines (sometimes superimposed on documentary footage), staged dioramas (recreating fragile memories), and immobile “actions” that counter the illusion of realistic images.

L’image manquante

As these real memories drift into an unreal space, so necessairly does Pahn as a autobiographical subject, so that this “decreation of the real” becomes, in turn, part of a larger desubjectivization of the film’s autobiographical reality. Since the real subject, who is Rithy Pahn, has in a sense been effectively erased by the extreme ideologically subjectivization of reality, Pahn returns as a disembodied voice and a variety of wooden and clay figurines. What remains of him is a phantom self whose look wanders and wavers before his past. At one point, Pahn’s own self teeters on the edge of this vanishing reality in a television insert where an interview with him seems to dissipate into the larger atmosphere of an unreal moving television image inserted into a landscape of radical stoppage.

To adapt a lost or missing reality can thus only be accomplished in The Missing Picture by gesturing toward it as an unattainable real. In Agamben’s term, the real as a “whatever singularity” can only be documented by representing it as a “cinematic stoppage”—achieved in this film as a layered montage across the image or in the literal immobility of its figures that gesture beyond themselves.16) At one point, Pahn’s voice-over comments: “When we discover a picture on the screen that is not a painting or a shroud, then it is not missing.” Here, in this film, however, there are only the stoppages of shrouds and painted selves.

Informing this impossible autobiography is the impossiblity of adapting this real to the cinema as subject. In a manner quite different from Agamben’s examples, The Missing Picture is thus both a deconstruction of autobiographical adaptation and more largely of the cinema itself. It attempts, in Agamben’s phrase, to “unveil the cinema with the cinema” by dramatizing the stops in intermedial shifts usually buried with in. Cinema itself disappears in this film like Pahn’s decreated memory of a Cambodian film studio before the revolution. What remains are only rusty film reels of Kymer Rouge prison camps as evidence of the full degradation of a cinematic real. In those four years of a reality of brutal devastation, as Pahn remarks, “There is no truth. Only cinema. The revolution.”

One sequence is especially illustrative of this action to “decreate” and “unveil the cinema,” as it offers real documentary footage that it then decreates within the context of a vastly different real. Here clips of the Apollo moon landing document a historical reality which then becomes doubly displaced into zones of the unreal that deny its presence. On the one hand, the Khmer Rouge soldiers refuse to believe the truth of this event; on the other, this triumphant footage of “one giant leap for mankind” gestures towards a (real) world impossible to imagine when contrasted with the contemporaneous brutality in Cambodia.

Over a conventional documentary footage from the period, Panh’s voice-over crytstallizes this difficult engagement between contesting realities: “I want to be rid of this image, so I show it to you.” To decreate the impossible real means ultimately to evacuate the reality of the image where, in Pahn’s words, “Conquest through emptiness is an image with glaring simplicity.” In the end, his triumph may be, as he puts it, that he has not found nor ever will find “the missing image”; a historical reality in this film has been painfully redirected to an open space of the real. If Pahn as subject and his memory as object remain beyond the image, their trembling real may be manifest only in phantoms of unseeable thoughts that gesture to the grounds for an ethical relation with the real: “For if an image can be stolen,” Pahn says “a thought cannot.”

Recreating the Real

In Sarah Polley’s 2012 Stories We Tell that open field of possiblity where the real dwells becomes an opportunity to recreate it through the force of repetition as montage. Like a classical narrative that slips off its usual path, Polley’s search for origins becomes a search for one’s own essential identity. More exactly, Polley approaches the crisis of her autobiographical encounter with a lost mother and father from a direction where the real opens up as a phantom far different from Pahn’s. She mixes documentary footage, talking-heads interviews, and, most importantly, reenactments, to interrogate and investigate that essential moment of identity as a “search for a father” in which a decreation of one real recreate it as another self.

Polley, who has a visibly and vocally prominent presence throughout the film, pursues the mysteries of her parents’s relationship and her own birth as a story that moves closer and closer to answers, while refocusing the accumulation of perspectives and commentaries by contrasting three possible biological fathers: Michael, the father who raised her, whom she knows and loves despite the professed difficulties in his marriage to Polley’s mother; Geoffrey Bowes, an actor in the Montreal production where her mother worked decades earlier; and Harry Gulkin, a well-known film producer, also present in Montreal at the time that her mother, Diane, became pregnant with her. These different father (figures) become a version of the larger and more philosophical contrasts that organize this documentary, among them the distinctions between the different “stories we tell” about our personal experiences and lives—to ourselves and to others.

The early part of Stories We Tell also introduces Polley’s siblings (Mark, John, Joanna, Susy) as well as other relations and friends of her mother, all of them presented as “talking head” figures who comment on the life of Diane Polley, their experiences with this dynamic woman, and her early death from cancer. Woven within this accumulation of commentaries and remembrances is a series of old photographs and home-movie sequences of the actress-mother frolicking around the house, playing at the beach, and at one point singing “Ain’t Misbehavin” on an audition tape. Gradually, this oblique portrait begins to reveal various differences in her personality that suggest an increasingly complex history of the mother, who for all of her extrovert exhuberance was “a woman with secrets.” Indeed the central secret that the film gradually uncovers is the surprising source of a pregancy that produced Sarah herself.

While the title of the film indicates a focus on various individual tales about the mother, the film accumulates, contrasts, and develops through these little narratives, which have been shaded and shaped by the limits and prejudices of first-person memory and which ultimately demonstrate how no over-arching perspective can fully explain, or even fully develop, the mother’s character, personality, and history. One of the possible fathers, Harry Gulkin, claims, toward the conclusion of the film, that only two people have the “right” to tell the story of Diane’s affair, since only she and he were there. Otherwise, he says, “you can’t ever touch bottom.” Indeed, for Polley, that elusive “bottom” of any experience or personality neither can nor perhaps should actually be touched or documented. While there may be a reality enmeshed within these diffferent perspectives, its status as a real remains a protean and elusive notion that can never be fully secured.

L’image manquante

Early in the film, Sarah describes the interviews that organize the film as part of an “interrogation process”—which is as much an interrogation of Polley as subject and her “essential self” as it is of the other players and family members in this drama. Just as it contrasts and complicates the truth of those accumulated interviews, Stories We Tell turns and twists that interrogative position in particularly contemporary ways. It reflexively engages and undermines the narrative interrogation that supports most memories and, at the samet time, reflexively calls attention to its own work as a personal film that uses theatrical and reflexive reenactments to undermine the objectivity of any perspective.

The film begins with a dramatically reflexive sequence in which Polley brings her father, Michael, to a recording booth where he hesitantly reads and reenacts the narration that we later find out he wrote for the film. At different points in the film, Michael reads this narrative commentary which, we eventually learn, he was inspired to write because of the climactic revelation that he and we experience and because of his subsequently renewed bond with Sarah. He reenacts as performance, in short, the reenactment he wrote of his life.

As he moves in and out of his own narrative, Michael appears sometimes as part of a third-person perspective on his own history, while, at other times, he expresses himself through a first-person testimony about his experiences with Diane. Throughout this reflexive narrration, Sarah regularly interrupts Michael to have him reread lines (“take that line back”) and so calls attention to the constructive fabric of his narration itself, set within her fragmented documentary. As a related strategy, past events in the film are often retrieved through what seems to be authentic found footage and home movies, but toward the conclusion of the film, many of these events and film clips are revealed to be reenactments with scenes reconstructed and actors playing the roles of the main characters. Like the deconstruction and theatricalization of Michael’s narrative, these reenactments make what at first seem like the traditional facts and actualities of documentary form into another representational dramatization that may or may not be an accurate portrayal of those facts, blurring the lines between different versions of the real as adaptations of reality.

These repetitions as reenacted montage thus open into a different place for the real made possible by, in the end, a climactic gesture. The film opens with a quote from Margaret Atwood “When you’re in the middle of a story it isn’t a story at all but only a confusion, a dark roaring, a blindness, a wreckage of shattered glass … like a house in a whirlwind.… It only becomes a story when you’re telling it to yourself, or someone else.” This dark, whirling house—like Nancy’s “world shaken, trembling, as the winds blow through it”—is that open zone where the real offers new possibilities, new values, and a new ethics. It is that zone that spreads and thickens the evidence of the real—like the passing reference to the parallel plot of Marriage Italian Style (De Sica, 1964)—where the quesiton of a self-evident patrimony gives way to a less determinant world where “Children are children and they are all equal.” This is a world where the elusive evidence of the real not only insists on decreating the image but allows for a recreative adaptation where the self-evidence of DNA gives way to the recreative evidence of imaginative affect and emotion, where “That great moment of truth” for Sarah and Michael becomes the gesture that she offers after all the stories have been told, a gesture that “makes [her] revelation of their non-biolgoical relationship worth it,” where, as Michael puts it, “was I or wasn’t I your father” becomes “an unimportant question.” As Agamben might say, here “repetition is not the return of the same but the return of the possibility of what was.”17)

Conclusion

In adaptive dramas of the real, documentaries—and more specifically biographical and autobiographical documentaries—typically moblize the phantoms of their historical agents to investigate, to adapt, and to offer evidence of the real as a place where ethics and value emerge as a possibility and potential. More traditional documentaries tend to stabilize that real and its agents as, ultimately, a self-evident value. At the center of the more reflexively adventurous of these films like The Missing Picture and Stories We Tell, however, tactics of cinematic stoppage, gesture, and repetition decreate as in Pahn’s film, and recreate as in Polley’s film, the real in order to open it up as a slippage that points to the interstices of a possible, and not a definitive, ethics. This interdeterminancy has increasingly created a space made visible through reenactments, where the adaptive process that is a documentary becomes doubled within that the look of documentary. In a world more and more contested and distorted by ideological claims of the real as self-evident, these kinds of reenactments—as seen in Pahn and Polley’s films—situate the real as a phantom whose acknowledgment as such is, for me, perhaps one of the most important educational tasks of adaptive documentaries today.

Editorial note

This is a written form of a lecture that Timothy Corrigan presented in 2019 at Ji.hlava International Documentary Film Festival. This essay (with some differences) was also published at A Companion to the Biopic (ed. Deborah Cartmell. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2020).

Notes

3) Jean-Luc Nancy, Abbas Kiarostami: The Evidence of Film, trans. Christine Irizarry and Verena Andermatt (Brussels: Yves Gevasrt, 2001), 10.

4) Ibid., 12.

5) Ibid., 16, 18.

6) Ibid., 22-24.

7) Ibid., 24.

8) Ibid., 24, 44.

9) Cinema and Agamben: Ethics, Biopolitics, and the Moving Image, ed. Henrik Gustaffson and Asbjørn Grønstad (New York: Bloomsbury, 2014), 58, 8.

10) Giorgio Agamben, “Cinema and History: On Jean-Luc Godard,” in Cinema and Agamben, 25.

11) Ibid., 26.

12) Bill Nichols, “Documentary Reenactment and the Fantasmatic Subject,” Critical Inquiry, Vol. 35, No. 1 (2008): 77.

13) Ibid., 77-78.

14) Ivone Margulies, “Exemplary Bodies: Reenactment in Love in the City, Sons, and Close Up,” in Rites of Realism: Essays on Corporeal Cinema, ed. Ivone Margulies (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002), 220.

15) Patrick Brzeski, “Busan: Cambodia’s Rithy Panh on His Cannes Winner The Missing Picture (Q&A),” The Hollyowood Reporter (October 6, 2013), hollywoodreporter.com.

16) Agamben, “Cinema and History,” 27-28.

17) Ibid., 26.

Cited films

Anna Karenina (Joe Wright, 2012)

The Times of Harvey Milk (Rob Epstein, 1984)

Caro Diario (Nanni Moretti, 1993)

L’image manquante (Rithy Panh, 2013)

Matrimonio all’italiana (Vittorio De Sica, 1964)

Stories We Tell (Sarah Polley, 2012)

Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, 1958)