Urge to Delve Into Underground

“On my way here, just round the corner in Spálená Street, I met a man, who was walking with a puma on a leash, instead of a dog,” said the director Miroslav Janek, starting off our interview about his new documentary film Olga, a portrait of Olga Havlová, which premiered at the One World festival.

After the film’s premiere I was surprised that the tabloid Blesk daily managed to find information in the film which they found worth publishing. Something similar happened also in the case of Citizen Havel. What do you do to avoid tabloidization in your films? Don’t you tend to ignore some of the personal topics?

I don’t mind tabloids writing about Olga or Citizen Havel. It only attracts new audience, who would not otherwise watch the films. And there is not a topic I would intentionally avoid only to change the film to my own image. The only reason why I did not include so many things in both Citizen Havel, and Olga, was that there was no more space for them. Films cannot be never-ending.

What do you think of the reviewers who accused the author of Citizen Havel of making the film on order by Havel’s followers to create an iconic image? When Olga is shown on TV, it can be expected that some of the reviews will use the same arguments.

Indeed, I hold Havel’s followers in greater esteem than these idiots who are ridiculing them. When Klaus sent his message that “truth and love have finally prevailed over lies and hatred” (based on Havel’s slogan inspired by the Czech national motto “Truth Prevails”) from Brazil when he learnt that Zeman had been elected for president, my hair stood up on end. It was such an unbelievably appalling thing to say.

Olga - an excerpt from the film, in which Olga Havlová clashes with Václav Klaus

Was the latest film Olga meant to be an amendment to Citizen Havel? To what extent were you affected by the work on Citizen Havel?

Apart from the fact that Olga Havlová was Václav Havel’s wife, those two films have nothing in common. They are formally completely different. Citizen Havel was made by Pavel Koutecký, the material had been ready and I was only an editor who had to work with what was available, although Tonička was my co-editor, too (Janková, editor’s note). Whereas in the case of Olga, I started from the scratch. It is also composed of archival materials, but they come from all sorts of sources. And yet, thanks to Citizen Havel I got to know Olga a bit better. I could feel her persona and found out what impression she makes on the screen.

Did you ever meet her?

I never met Olga but I have heard about what she was like, for example, from Bohdan Holomíček or Andrej Krob. And when I read Kosatík (“A man has to do what he is strong enough to do.” Life of Olga Havlová, editor’s note), I felt like I’d long known her. As if she had been an old friend of mine, sort of a soul-mate.

You spent many years in exile. When exactly was that?

I was out of the country in the years 1979 – 1996. But I have not been left completely unaffected by my stay abroad. Before I left, I had been in touch with many people who were active dissidents and I attended various seminars held at private apartments. When I was collecting material for the film Olga, both written and audiovisual, I came across references to many of my friends. Even the samizdat magazine Nový brak (New Pulp), published by the underground library Svépomocná lidová knihovna Hrobka, whose members used to meet at Andrej Stankovič’s place, featured a story about myself.

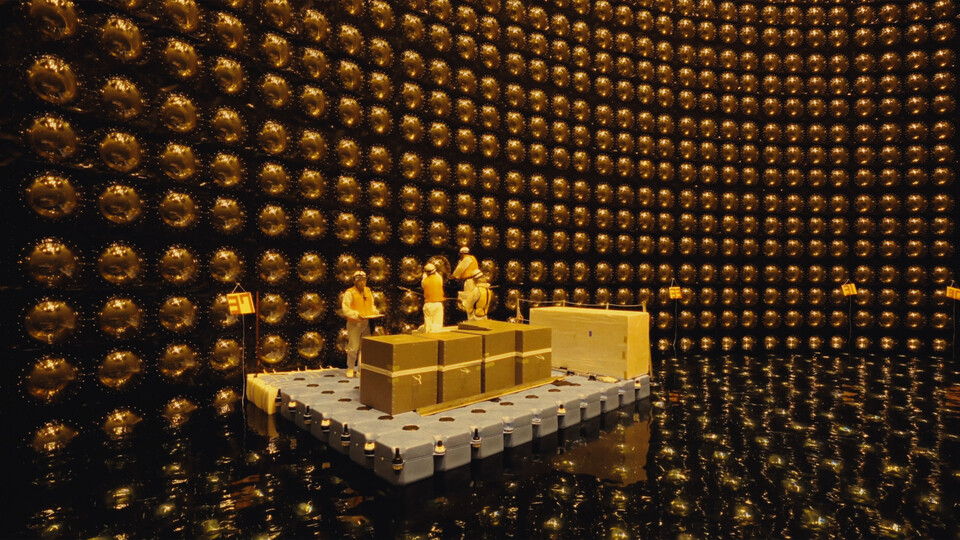

How did you find the archival materials from the period of dissent? Is there something revealing in Olga what has been considered long lost?

Certainly, there are numerous shots that have not been used in any feature film. I mean mainly private archives of Andrej Krob from Hrádeček, for example, the last scene when she is throwing a stick to the dog. Or black-and-white footage recorded at parties on a 16mm film. I found them in the archives of Czech TV, which purchased about a half of the samizdat Videojournal. However, this tape was kept separately in a safe. But they opened it for us. Of course, the most precious footage was that of Olga herself.

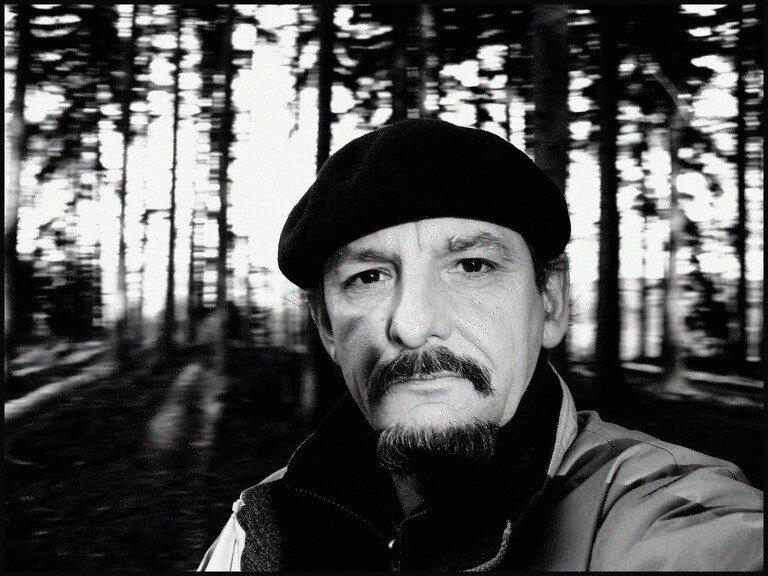

Olga

“Free” America

The film is, to a large extent, concerned with the period of Czech history which you did not personally experience. Is this fact one of the reasons why you find this period so attractive?

I did not experience the period of dissent, and perhaps I like to experience it through my films. In the case of Olga, I knew that this period was of utmost interest to me, but not because of dissent. I was interested in the spirit of this movement, their world, their humour. It provided a sort of a counterbalance to the surrounding idiocy, the stupidity of the police. And this may be why so much space in the film is dedicated to this issue, although some might find it inappropriate.

Do you consider your films to be faithful renderings of the period of dissent?

It’s important to me to remind others that people used to have a distinct face, they were individualities who were able to look at the world with perspective. They used to be personalities. Today, everything is blurred. The common enemy is nowhere to be seen and unification based on spiritual affinity is less and less usual. When my students saw the rough cut of the film, they said: Wow, that’s something to envy!

And is it easier for you – being unaware of the tensions between the individual actors – to approach this period as a filmmaker?

Each and every community has some tensions. If I was to focus on personal relations, I would make a completely different film. And, pathetically speaking, I can feel a great freedom in dissent. It might also be affected by my experience living in exile. When I suddenly saw the “free” America we dreamed about, I was surprised to find out that Americans don’t have much inner freedom. All the more I value the experiences of people living here under totality.

You came back in 1996. Václav Havel was the president and many people from the underground movement started to work in state administration, the standard democratic apparatus was set in motion. But do you think we can still find inspiration in the spirit of dissent?

I feel the urge to delve into the underground movement in the recent years. Not into the underground of those aging members of the movement who I make my films about. I am looking for a new and different underground. What is it then? Some kind of opposition against the establishment. And that should really be emerging now, because people are quickly getting dumb. It is not only caused by all sorts of crooks in political offices. Prosperity makes people stupid.

More silence

Your latest films are portraits of famous figures: an actress Vihanová in Burning, Havlová in Olga and an underground musician, poet and garden designer Brabenec in the documentary you're shooting at the moment. The films touch upon current affairs and partially take place in the present, but they are more related to the past, to the disappearing “icons”. This might seem like an evasive action, or even resignation, unwillingness to deal with the present.

None of the three films is conceived as a return to the past. From my perspective, Burning shows difficulties that people can experience even in fifty years from now. Of course, I deal with the trouble Vihanová got into, but the film does not aim to re-enact the past. It only sets the film somehow in motion. It is only a tool. And the same goes for Olga. I always try – without being hundred per cent successful, to provide the film with some added value. To me, Olga is an inspiring personality who remained true to herself. That is a topic for me. In the case of Vihanová, the question is, whether it is worth it to sacrifice your personal life to your ambitions. Brabenec naturally speaks about his time in prison. But even in his case the film is not only about the past. It is more about inner freedom. At least I hope so.

Your films often focus on personalities but they are not too wordy. They emerge from situations, images, author’s inner freedom that – as you say – you try to find in others, too.

It is interesting that you say so. I am in agony when I see that my films are too wordy. I would want my films to use as few words as possible, but I think I have not been much successful in that respect. And I would love to make a silent film. I would just be sitting and looking at the world from my window. I would like my films to be more silent.

Burning

Translated into English by Bára Rozkošná.