To hear children weeping in a photograph

The journalistic war photos that we have, unfortunately, seen so frequently in recent months are primarily meant to inform us about the conflict. However, they often strive to take on a subjective character and become political actors. Photographs of suffering children play a special role in this transformation. What role? Visual theorist Andrea Průchová Hrůzová explains in her blog.

Although we now live in a flood of moving images, whether it’s the glut of comic book heroes on cinema screens or the rapidly proliferating amateur video content on social media, photography still retains its prominent position, and it is not disappearing from visual culture. This is especially true when it comes to the genre of wartime photojournalism, which takes up the task of reporting on conflicts. However, it often seeks to assume a subjective character and transform from a mute documentary record into an important political actor with a voice that stirs the masses. And photographs of suffering children play a special role in this transformation.

Documenting the war from up close

Representations of wartime catastrophes are among the key documents of human culture. Written records in the form of mythical, religious, and epic narratives and maps fill libraries. Pictorial records can be found in early stone reliefs and later in many paintings but also in the public space in the form of monuments and statues of military leaders and politicians.1) Yet photography holds an essential place in the documentation of war.

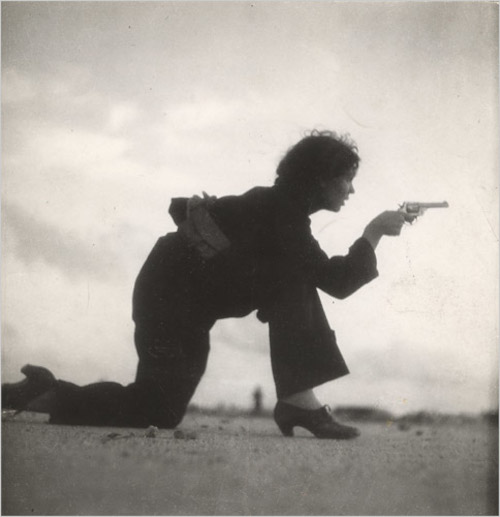

On the one hand, this position is determined simply by historical realities. Photography became the first technical image – a picture created by means of an apparatus and not “merely” by the human hand – that conveyed the experience of war to the general public. In the history of photojournalism, the documentation of the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) is considered groundbreaking. According to philosopher Susan Sontag (2002), it represents the first fully modern visual coverage of a war. Indeed, it was during this conflict that photographers began to circulate inside the front lines, and the output of their work became readily available to an international audience. As the history of photography reminds us, the genre of modern war photography was established also thanks to a technological transformation. Professional photographers got their hands on small, lightweight, portable cameras that used 35-millimeter film. These made it possible to take pictures from up close, resulting in photos that were dynamic and highly emotional. Moreover, the Spanish Civil War was a conflict that was, logically, well-covered by the key news agencies of the time, in whose interest it was to obtain the most attractive visual content. They therefore reached out to those photographers who already had greater experience documenting war. Among the best known was the duo of Robert Capa and Gerda Taro, whose images have assumed an almost iconic character.

What if it were me…

While an explanation of the unique position of war photography lies, on the one hand, in the historical, technological, and media contexts of the time, on the other hand we have the entire spectrum of reflections on the nature of photography and in particular on its relationship to the past. In the case of war photography, capturing the past is understood primarily as the creation of a credible record of past events. War photos are assigned documentary value as they aim to inform about a conflict. At the same time, however, they frequently offer a humanistic perspective because they focus on specific actors in the war. Whether they are photos of fighting men and women, fleeing families, or destroyed homes containing the remnants of personal effects, images of conflict are often framed by human stories that engage the audience. The documentary character of a journalistic photo thus encounters a principle of construction that is of a technical (the way it is shot) and social (the “narrative”) nature, and these intertwine and influence each other.

For the viewer, however, war photography retains a special magic that relates to capturing the past on an even deeper level. As Susan Sontag notes in her book On Photography, “All photographs are memento mori. To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability” (Sontag, 1990, 15). In relation to photos of conflict, however, this consideration takes on further significance. Viewing photographs of the dead, dying, or endangered constitutes a literal articulation of the reminder of the impermanence of human life. Whereas in ordinary photos, in which time has been imaginarily “frozen” by photography, the stories of actors or subjects may continue, in war photographs they have ended or are threatened with an imminent end. The awareness of the passage of time is fully condensed in war photography. In his book Camera Lucida, philosopher Roland Barthes speaks of experiencing the intensity of an image precisely insofar as it captures the phenomenon of time. Specifically, the author is interpreting the 1865 portrait of the American attempted assassin Lewis Payne, who is waiting in a cell for the execution of his death sentence by hanging. According to Barthes, this photograph offers us the experience of the anterior future. “This will be and this has been” merge into one and speak of “death in the future” (Barthes, 1996, 96). Barthes refers to this extraordinary experiencing of finitude through photography as punctum.

Photojournalism theorist Barbie Zelizer uses the term “subjunctive voice” to explain the impact of wartime images. She sees it as a specific quality of photography that makes the image speak directly to the audience and leave an emotional mark on them. Indeed, the cruelty of war captured from a humanistic perspective leads us to ask: “What if I found myself in their place? How would I feel if those lifeless bodies of someone’s loved ones belonged to my own dearest?” This voice stems from the documentary nature of war photography, which allows us to treat the images as evidence of the horrors of the past; however, their literal articulation of the experience of death and their condensation of the passage of time speak to us personally, injuring and engaging us. This ultimately creates a space for the projection of the self into the photograph. Thus, photos of the Spanish Civil War not only bear traces of the transformation of the political, technological, and media landscape of the time but also function as traces imprinted on the individual and collective memory of those who view them.

A letter to grown-ups

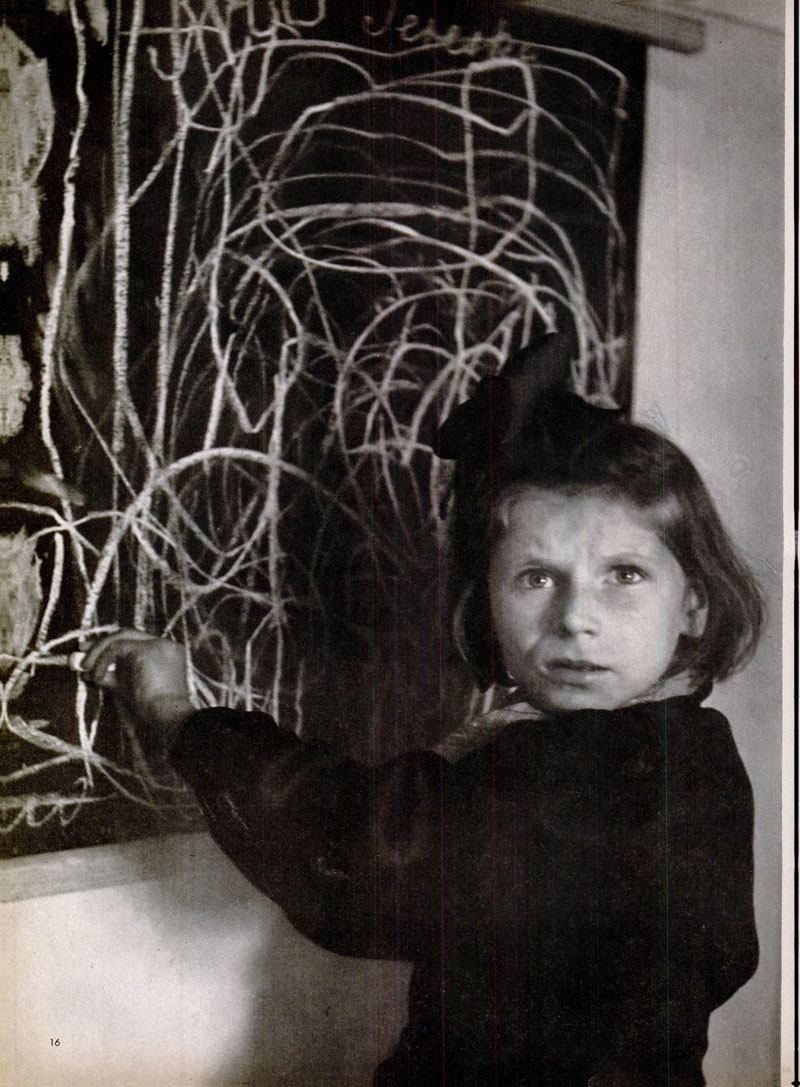

In addition to Gerda Taro and Robert Capa, the Polish-American photographer David “Chim” Seymour (1911–1956) was also renowned for his images from the Spanish conflict in the 1930s. He also founded the well-known commercial cooperative Magnum Photos in 1947 together with Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and George Rodger. This was after the end of the Second World War, when Europe was facing many postwar traumas and struggling to return to normal life amidst the ruins. In the spring of 1948, Seymour was commissioned to create a photographic documentation of child survivors of the war. The project’s commissioners were two newly formed organizations: UNICEF, which was dedicated to child welfare, and UNESCO, which was concerned with cultural heritage. Seymour, whose practice focused on the portrayal of human actors, seemed the perfect candidate for such a task. He spent a total of six months travelling through Austria, Greece, Italy, Hungary, and Poland and shot 257 rolls of film. These were the basis for the photo book Children of Europe, published in 1949. The book contains 52 images that acquaint the reader with some of the most powerful images of war – representations of children. Children suffering from hunger, poverty, or mental illness, children who were sexually abused or survived concentration camps. The most famous photograph from this series, although it is not included in the book, is considered to be the image “Tereska”. It shows a girl with a bow in her hair standing in front of a blackboard on which she has drawn clusters of circles. The girl is a survivor of the Holocaust, during which she lost her parents, and the circles are meant to represent her idea of home. All of the children, including Tereska, are usually looking directly at Seymour’s camera. Tereska’s eyes are wide open, almost bulging. As if she doesn’t even register the camera. Her gaze remains absent, trapped somewhere far away from the space and time of the encounter with the photographer.

David Seymour provided the book with a short introduction and an afterword. Both texts are written from the perspective of an anonymous child speaker. The introduction is entitled “Letter to a grown up”, and it sets out the theme of the book in no uncertain terms: “I would like to speak a little about myself, but mainly about the 13,000,000 abandoned children in Europe who had their first experience of life in an atmosphere of death and destruction, and who passed their first years in underground shelters, bombed streets, ghettoes set on fire, refugee trains and concentration camps” (Seymour, 1949, 5). While the first section of the book documents the suffering of children caused by war, its second part gives room for hope. It captures groups of children playing amidst the ruins of cities or returning to school. The book’s conclusion makes an appeal that in the future, when the children of war have grown up, there should no longer be multitudes of lost children’s bodies and souls. Otherwise, we are allegedly in danger of an irreversible shattering of faith in human culture.

Hearing one’s own weeping

Looking at the subjects of Seymour’s photographs and reading the final appeal, we can critically reflect on the ways in which the author framed his images and on the ideological use of the publication in the context of the politics of postwar Europe. Some theorists, for example, have pointed out that the global image of suffering rendered by this and other postwar UNESCO publications erases the local cultural, political, and economic specificity of the issues that are key to understanding the suffering depicted. On the other hand, it is hard to dispute the great emotional impact that wartime photographs of children have – and not only on those who are parents themselves.

Building on the contemplation of the subjunctive voice of photography, I thus think of these photographs as images that address us directly, but in a specific way. Instead of asking, “What if it were my family? What if it were me?” photographs of suffering children draw us into the present moment and say, “It is me.” After all, each of us was once a child. Each of us remembers fragments of that complicated time of rapid maturation in which sensitivity, imagination, intensity, and the need for love reach a peak, which is supposed to come in the form of the touch of a parent or some other constant and loving guardian. These photographs do not make the present subjunctive but rather thrust us into it. They are a relentless threat to us and to the children inside us – children who are content, injured, and never grown-up. They stir up those feelings inside of us that we are forced to leave behind during adolescence, sometimes all too painfully. And suddenly they’re here again. And again, they’re threatened with an end. An end that children – as opposed to adults – are not responsible for in the case of war. Thus, I think war-time photography of children is not only a memento mori in the sense of the touch of death but also a memento mori in the sense of the end of childhood as a time of play and innocence. If, as Zelizer says, when we look at war photos, we hear their subjunctive voice, I think that when we see images of suffering children, we hear their weeping – our weeping.

---

Literature

BARTHES, Roland. (1996). Camera lucida (Richard Howard, Trans.). New York: Hill and Wang. (Original work published 1980)

SEYMOUR, David. (1949). Children of Europe. Paris: UNESCO.

SONTAG, Susan. (2002, December 9). Looking at war. The New Yorker Magazine. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2002/12/09/looking-at-war

SONTAG, Susan. (1990). On photography. New York: Anchor Books. (Original work published 1977)

Notes

1) In this respect, it is worth looking at the public space around us from a decolonial perspective and asking which groups (e.g., women and representatives of ethnic minorities) and ideological positions are (not) visible in this kind of politically organized public space.