This is not a woman’s film about breastfeeding

Let’s start somewhat unconventionally. Who shot your film?

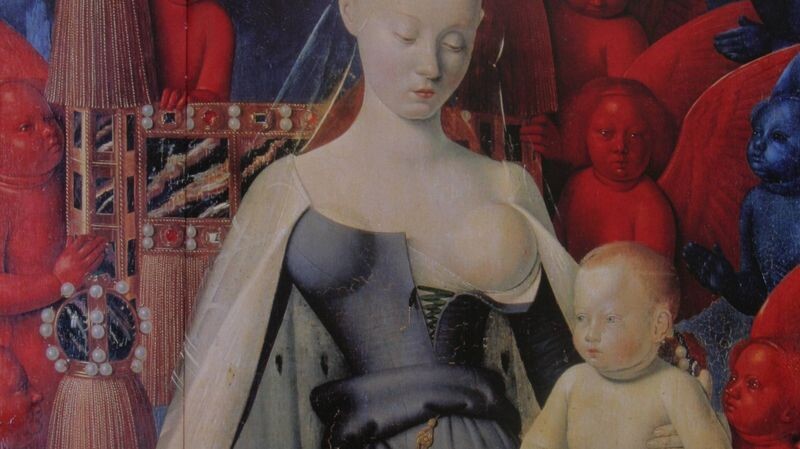

It’s good that you put it like that. This film is carried along by images from my imagination that were dancing about on a kind of movie screen in my head. They came into being on their own just as I saw them; they were not constructed. So the question of who made my film is a valid one. I studied theology and am very interested in Christian art, primarily contemplative paintings of saints or Madonnas with child, of which there are countless versions, and I was very interested in the “noetic background” of these portraits. For me, Mary with the child symbolizes the fact that man has the power to be born again, to change and grow towards good. I believe that every person, man or woman, has the ability to give birth to something divine into this world, or to create the space for it, but in some way it relates to the pains of labour. Because everybody has to start with himself. And the divine – a child – it is fragile, it requires care, space, nurturing, it must be sustained so that the good that is a sign of the divine will not die. This is what my film is trying to capture.

You are interested in the “noetic background”. To what extent do moving images have the ability to be truthful?

Film in general is more what isn’t than what is. A film presents images and ideas, but in order to be filmed, this requires a far more important and invisible process, one that exists beyond “cropped reality”. That is why I am more interested in what did not make it into a film that what is there. The images represent something, but they also hide and exclude something. It is important to be aware of this, primarily because a director tries not to constitute one truth and is in a way responsible to entirely different parameters than the external, produced ones.

Let’s stick with the title of your film. On what principles does the relationship of the body to “your body” function in this film?

This might sound strange, but for it is one of my fundamental beliefs. Our lives, in addition to being a part of this world, also belong to the great cosmic body. This is a vital two-way relationship involving certain burdens and difficulties, but I nevertheless believe that we should accept this process-based relationship as something that brings us joy and happiness. Our body, which during pregnancy becomes something alien, a kind of automaton, is one gate on the path to a deeper understanding of what I have in mind. During pregnancy, my body became a home for another body; it made a space for new life. This results in a process of self-denial. And this process is similar to the process that happened to the cosmic body. My belief includes the Cabbalist explanation for the creation of man, according to which man can only exist if god – god as some kind of omnipotent entity – withdraws and gives man the room to be independent from god, to be free.

You spent almost two years making this film. Why are the exteriors dominated only by winter?

I wanted it to be winter. It represents fragility as well as firmness. Snowflakes are fragile; they fall and change shape, change into water; they are a different form of life.

They see sterility as the norm

During one discussion you declared that the media often depict children only alongside happy and beautiful mothers. Is the media image of motherhood really like that?

Women who haven’t had children yet receive an image of them based on what is available. If they don’t search deeper and don’t think, then we really do encounter for the most part images of an ideal motherhood with pictures of beautiful and happy, financially secure mothers with a child at their breast. And they see this false sterility as the norm.

In your film, mothers are presented as partially identifiable individuals, but the children are indistinguishable, undefined, and without personality. Why does the film only show children when they are crying? Or nursing?

My aim was to present the mutuality of mother and child as a basic and overlooked dimension of our relationship to the world. This applies to the most important scene, which comes before the opening credits: nursing in quiet. For me, the close-up of a giant breast and a child’s head is highly emblematic. The child is nursing, sucking, but also growing. And its lack of definition represents a life that we have not yet fully understood, and experiences that are only now becoming personal, that still need to be formulated. What is more, I didn’t want there to be scenes of cute and adorable children. That would have been a different movie. Sure, I’ve got tonnes of such footage, but I didn’t want my film to be me masturbating over the beauty of my children.

To what extent does the film capture the transformation / deepening of the relationship between mother and child?

There is no transformation there. In the film, I represent a non-changing icon. It is something like a painting that we look at. This can be seen in the longest scene where I am nursing my child. These are moments when you know that time is flowing, but at the same time the image we are watching is like a photograph or like one film frame. This provides the opportunity to pause and contemplate. This stylistic approach continues to entice me, and I think that I will continue to use it in the future. I am hypnotized by the question of the foundation of the structure of cinematic time.

Rather than pausing, I understand this scene more like an agonizing extension of time. In my opinion, this scene would cause me to contemplate only if it didn’t end with the child relentlessly and inconsolably crying.

I understand. But why is a child’s crying so unpleasant that we want to eliminate it? What if this child’s crying represents the crying of our world, which is raising its voice and calling for help? And I want for it to be heard. I really did see it as an opportunity for contemplation, for a different quality of time where the difference between “long” and “short” disappears because that shot is so long.

You can see the film for free at DAFilms.com

One of the heart valves of the film

A child’s crying, its smacking noises, brutal white noise. Sound in your film has a strange rhythm.

This film’s audio track is backwards from how it plays out visually. In the beginning there are crying children, they are fed, then they cry again and are fed. And the last sound that you hear is from pregnancy – the sound of my unborn children’s heartbeat while still in the womb. In my opinion, that sound gives the shot of me on the ball a sense of magic. The last scene from home with my husband was supposed to be like a visualization of this heart.

You use unusually long periods of silence. All of a sudden, the viewer ceases to focus only on the film and feels as if he has left the cinema. He becomes aware of his presence and that of others in the movie theatre. He begins to be aware of the sounds of the people around him …

Exactly. I want for everybody to be in that room together, and to watch it together. When there is a sudden silence, the people in the theatre become aware of it. They start to become aware of each other. My aim was to bring the movie screen down among the people. At the same time, I wanted to allow the viewer to hear himself. This, I think, is one of the heart valves of the film.

You added the final shot of the film before FAMUFEST – the scene when you are close to camera, holding one of your twins, and your partner on the ball is cautiously holding the other. It wasn’t in the original version shown in Jihlava. Why suddenly this scene, which more than any other resembles a sappy home video?

I decided to reinsert this shot of all of us, which had originally been edited out, because I wanted to show that it is a shared thing, that it isn’t exclusively my experience, but the experience of all people: our ancestors, our families. I understand the shot of my partner on the ball as a confirmation that this is not a woman’s film about breastfeeding, but that it extends onto more universal and abstract levels.

(Special thanks to Marika Pecháčková)

|

|

Viola JežkováBorn 16 October 1979 in the foothills of the Eagle Mountains. She grew up with her two brothers in a small town, by the river, in the woods and on the hills. In 1999, she began studying Protestant theology in Prague, but her dream of becoming a pastor gave way to an interest in philosophy, Judaism, religious studies and history (of art). In 2006, she completed her studies with a master’s degree, and in 2007 she began studying documentary filmmaking at FAMU’s Department of Documentary Film. In 2012, she was accepted to the master’s programme. That same year, her film My Body’s Body was named best documentary at FAMUFEST. |

The film presents a kind of mental space of timelessness, on whose margins exists the mother’s body. Its personal vocabulary consists of images and sounds from the first months after the birth of the filmmaker’s children. The film thus juxtaposes the usual ways of depicting and understanding motherhood against her personal experience, which allows us to come closer to the reality of new life and the reality of motherhood. The space between motherly love and postpartum psychosis is filled with intimacy and fragility. The micro-plot of each scene contrasts with the rigidity of unchanging time, framed by the white winter landscape. The film thus presents something utterly basic and fundamental.

-

You can watch the film for free at DAFilms.cz