The Unbearable Movement of History

Pictures from the history of a nation or self-absorbed exhibitions of five young filmmakers? In case of a film like Gottland; and a nation like the Czech one; these options do not exclude each other. The shift of perspective in the film which brings Szczygieł’s slightly alienated description of the life stories of several figures of the Czech 20th and 21st century to the screen was discussed by film art historian of the National Film Archive in Prague Iwona Łyko (IŁ), translator from Polish, author and traveller Bára Gregorová (BG) and analyst of Hospodářské noviny daily Petr Fischer (PF). Like in case of the book, in case of the film, too the question of historical convincingness suggests itself first. How fictitious is the film?

BG I have perceived the film Gottland as a documentary from the very beginning; perhaps because I know Mariusz Szczygieł, the author of the eponymous book, as a reporter and documentary is naturally linked to a reportage text. In Polish literature, there’s a numerous reportage school, with wartime author Zofia Nałkowska and internationally popular Ryszard Kapuściński being undoubtedly its predecessors. In Czech literature, this format is actually not that common. The space between fiction and reportage, as known from Polish literary reportages, is what characterizes the very film documentary.

IŁ I definitely consider the film a creative documentary. When we look at the previous works by the directors who have contributed to the film we can see that they continue in the direction they have indicated in their previous documentaries. For instance, Lukáš Kokeš treated Baťa’s story in a way that is reminiscent of his previous films. These young filmmakers do not abandon the link to reality while emphasizing their own perspective, style and poetics.

PF To me, the film represents a sort of “pictures from the history of the Czech nation” and the comparison with Vančura’s Pictures from the History of the Czech Nation makes it clear that Gottland only depicts some kind of “marginalia”. Nevertheless, these very marginalia show the approach to history which is also typical of “big” history; i.e. the filtration of reality, the things we notice, the fact that we always approach history; even the most recent one; from a certain creative distance. As for the formal aspect, I have rather become absorbed in the images and let them speak to me while watching the film. Which is what the film is quite good at.

Gottland

Post-Baťa Era

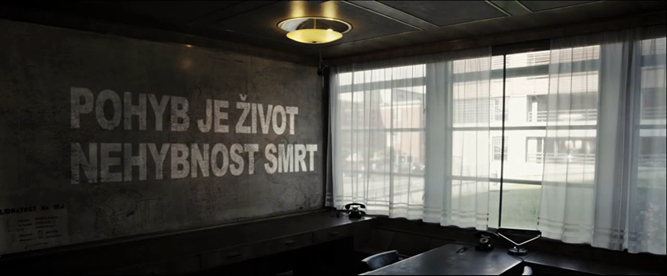

BG What I like is the emphasis, both in terms of form and content, put on movement in the first film by Lukáš Kokeš; movement means life, immobility means death. There is also the contrast between an enlivening movement which leads to a certain destination and a movement that is mechanical, inevitable, inconsiderate. Perhaps it’s the movement of history that flows spontaneously and repeats itself hermeneutically, or rather “winds itself up”. All of the stories are interconnected by this theme and I feel that the filmmakers have thus managed to capture the theme of the whole twentieth century.

PF What I found essential was the metaphor of the circle, also introduced by the first film, which captures the Baťa circle on which shoes are produced; a rare, now almost non-existent form of manufacture. The circle opens up and we are heading somewhere, without knowing where though. To me, this is a sort of a goodbye to the Baťa period. Baťa was an ideal; utopia; constructivism; an expression of the idea that we can create and organize the world and as soon as we’re ready things will be just fine. However, the circle has been disrupted and the film shows the consequences of its opening; history cannot be closed; history must be constantly revisited.

It must be rather hard to follow the film as the film requires the awareness of a certain confusion or aimlessness of the events in Czechoslovakia after 1948 and 1989. The return to Baťa was not possible; yet there is no other direction.

BG I have watched Gottland with a Russian friend and had to explain the Czech way of looking at things to her. Again I have convinced myself that the Russians perceive the flow of history in a different way than most European states do; in an expansive, centrifugal way; not as a spiral but rather as a list of similar events under the guidance of a strong, authoritative ruler. That’s why I think the film is rather focused on western civilization. Viewers from the East or perhaps from Africa may not comprehend its poetics and meaning.

IŁ The film version of Gottland might be difficult for the Polish viewers as well, especially if they’re not familiar with the Czech culture and specifics of Czech documentary film. Polish documentary film has a different poetics and local audiences thus have different expectations.

Gottland

Gottland in Poland

PF You Poles have a different notion of terms like nation and history; history must go forward and the nation will be big. On the contrary, in the Czech Republic, there is the melancholy reverberation of the lyrics of the anthem “Where Is My Home” which shows both the relativization of everything and a constant self-reflection; as well as autoreferentiality. I’m not surprised that the Czech creative documentary is autoreferential and that this is difficult for the Poles to comprehend.

IŁ We don’t know your history; we rely on stereotypes when thinking about Czechs. Szczygieł has surprised the Poles with his book and has changed their view of Czechs. What he really says is: “Look, they do have history. It may be different but it is still tragic. Even without a Warsaw Uprising.”

BG I have to admit that the Poles I know are fascinated by the Czech nation; whereas we perceive them as black marketeers, which is a prevailing stereotypization. In this respect, Szczygieł has done a good job, as he doesn’t look for stereotypes, rather showing the unique aspects and thus revealing our own mentality, hopefully even to ourselves.

IŁ It’s interesting to realize the difference between the goal of the book and the film. The film treatment of Gottland was made by Czechs and a Slovak; they have thus really expressed their own view of their history. On the contrary, Szczygieł has discovered Czechs, is enthusiastic about them and shows them to the Poles, looking for things in Czechs that we Poles don’t know, that we lack. It’s a way for Poles to think about themselves. We usually go out to the world to learn about ourselves and, at best, start reflecting on our “autostereotype”.

PF The film version cuts off the layer of the straightforward view of a reportage which is typical of Szczygieł. The filmmakers didn’t perceive it as a challenge to film a different view of “what is different about us”.

BG I think that they have merely followed the stories. They have used a subject mediated, which is interesting, by someone with a different history. In his book, Szczygieł tabloidizes the stories a little, making them acceptable for the readers, which is lacking in the film completely. Perhaps that’s why the film may be incomprehensible not only to some Poles but also to many Czechs.

Gottland

Shared Sadness

PF I find it interesting that Poles learn about themselves by learning about others while it’s typical of Czechs to be withdrawn. What I mean is not Czech self-centeredness but rather a certain immersion in ourselves. In the film version of Gottland, this immersion adopts an even meditative tone. The mediation on Baťa literally attacks the viewers. The speed is terribly unnatural.

IŁ That’s what also makes it different from the book. Szczygieł’s Gottland isn’t sad but the Czech film version is sad, very sad.

PF What’s interesting is the way the atmosphere links the stories together. They share a certain tension, a trembling. It’s actually pretty surprising, as the addressed filmmakers are distinctive documentarists. Each of them has their own style; yet the film as a whole, across the individual parts, has a similar atmosphere.

BG Isn’t it because the filmmakers belong to the same generation? By coincidence, I and Iwona are also part of that generation. Just like the literary critics are trying to label the generation of contemporary authors as autobiographic, autoreferential, and “escapist”, it’s possible that there’s something similar among filmmakers as well. It could be that directors with a similar view of the world and history have met in Gottland.

IŁ In the Czech Republic, the generation of people in their thirties has a need to speak about recent history they have partially experienced. They somehow want to capture what’s happening, how, and in what context. The makers of Gottland seem to say: “We can get distanced from our present; we are able to say how we see it and what point of view we adopt.” I find that they also use the stylistic means to achieve it. Be means of form, they are trying to show that they’re not completely overwhelmed by their times; that they can look at things sort of from aside.

PF What’s interesting is the way such a distance is achieved; by means of diametrically different formal means; in the films by Viera Čakányová, who has chosen an animated form for her retelling of the life story of writer Eduard Kirchberger, and Klára Tasovská, who tells the story of Zdeněk Adamec. The formal aspects of the former film help to rid Kirchberger’s story of pathos. The film is based on a video interview with Kirchberger’s daughters. The family judgment of history, imprinted in the story of their own father, includes neither easy condemnation, nor forgiveness; only empathy and experience. The latter film, which also presents a non-hero afflicted by unjust history, is also narrated in a similar non-affected way, though without the effort at any empathy. Tasovská has chosen a very terse language, merely describing the facts and avoiding heroization. Adam’s deed, a protest self-immolation, is immediately forgotten, the media do not reflect it at all. Tasovská actually only shows a society that didn’t create a hero.

It seems that the filmmakers share a common approach to history which is most likely symptomatic of the whole generation. History hurts, it’s sad and it’s hard to go through it. However, there’s no sense of resignation, just a certain kind of sadness.

Translated by Tereza Chocholová