The tale of a vanished sea

Why did the water leave Muynak, and how did Joanna Kozuch, a Slovak director with Polish roots, create her animated documentary Once There Was a Sea (2021)? The film, which won the prestigious Sun in a Net Award and was named the best short film at this year’s animated film festival Anifilm, is now available to view at DAFilms.

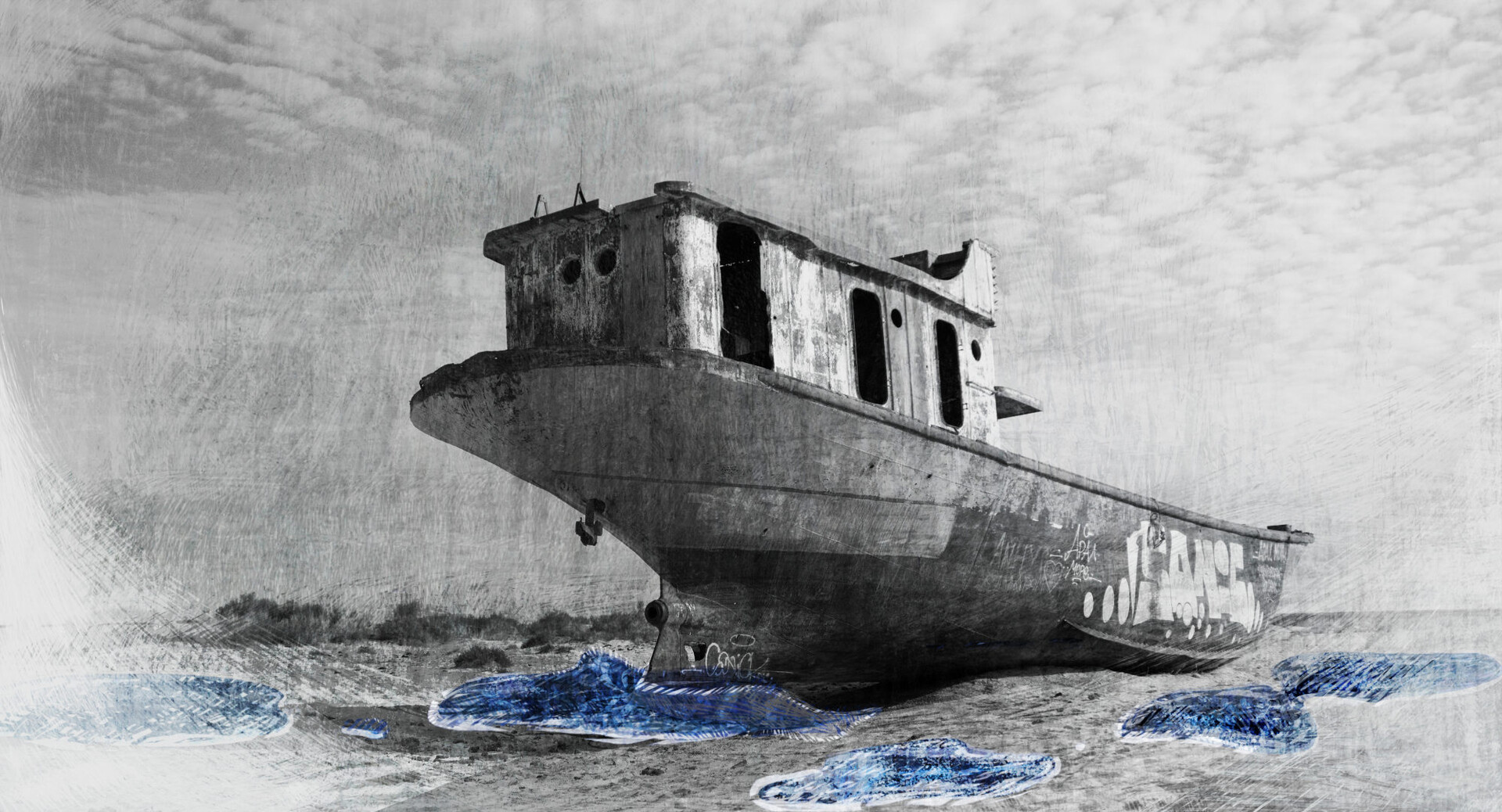

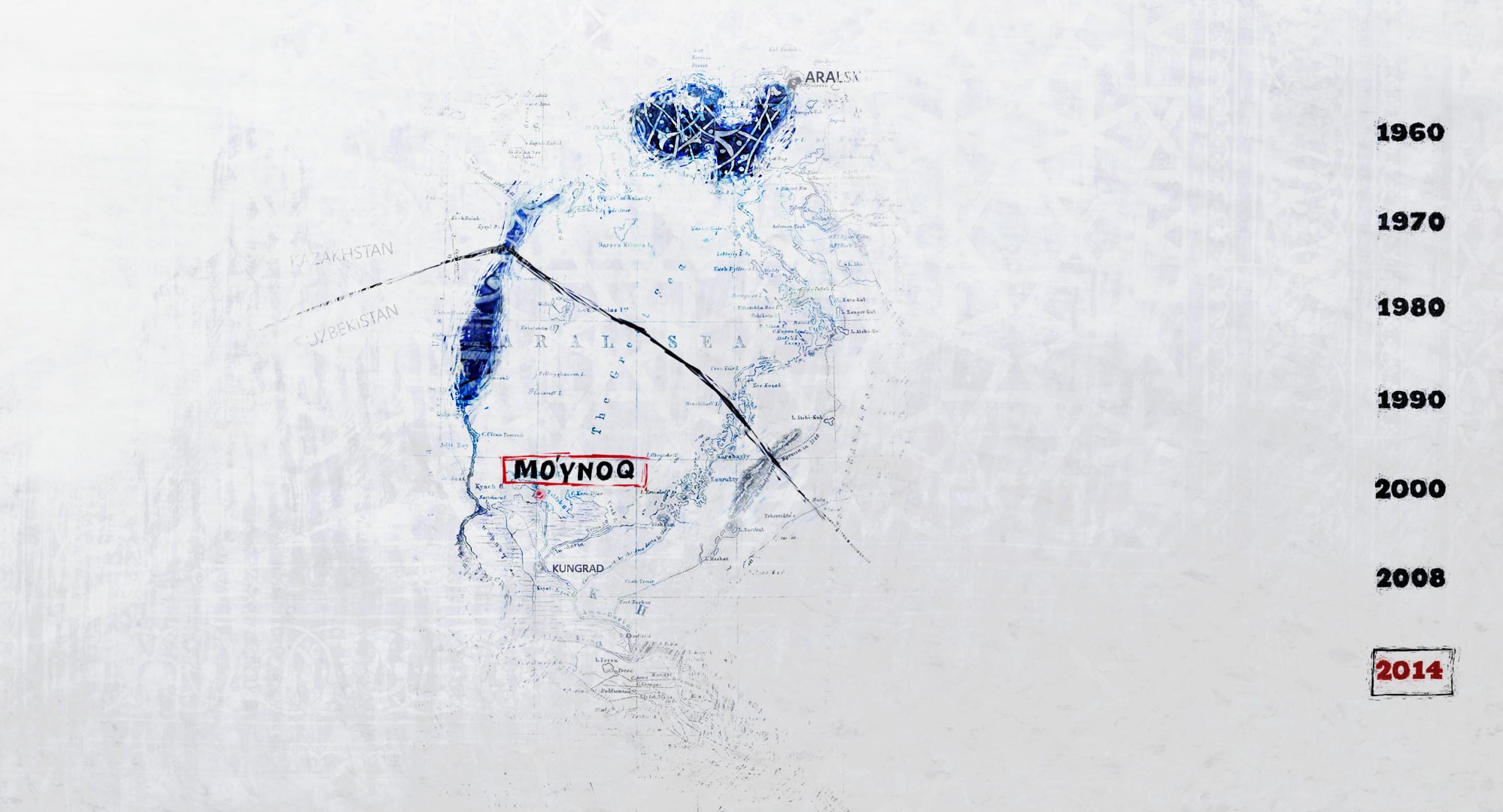

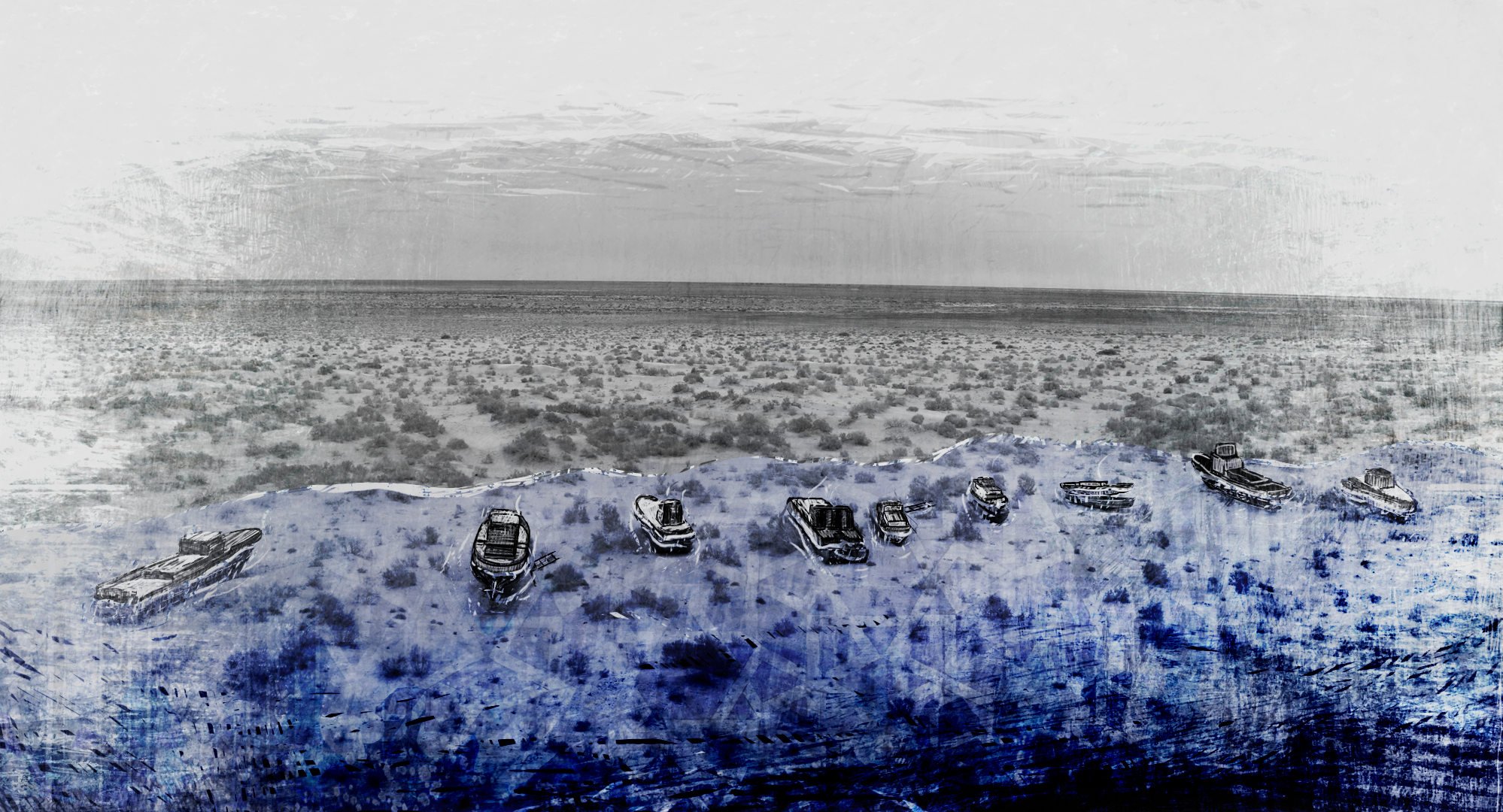

At the start of a decade of work on this film, there was a love of travel and the book of essays Imperium by the Polish reporter and writer Ryszard Kapuściński, which is where director Joanna Kozuch first encountered the story of the vanished Aral Sea. This ecological and human catastrophe dates back to the 1960s, when Soviet leaders decided to cultivate cotton in Uzbekistan on a large scale. “But no one dared to ask what it would cost,” Kapuściński says in his book. It took a mere two decades for half of Uzbekistan’s oases to turn into desert. Because cotton requires a lot of moisture, excavators carved deep troughs along the banks of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers. “The landscape was changing rapidly. Rice paddies and wheat fields, green meadows, beds of cabbages and peppers, orchards of peach and lemon trees were all disappearing. Cotton grew everywhere, as far as the eye could see,” Kapuściński describes in Imperium. To support the growth of cotton, the land was also bombarded with tonnes of artificial fertilisers. On the Uzbek side of the Aral Sea lies the settlement of Muynak. Even for Uzbeks, it’s the middle of nowhere. Once a fishing port, it is now a salty desert sixty miles from the sea. It has disappeared. Instead of a harbour, you’ll find the rusting hulls of fishing boats and barges stuck in the sand. “In the last twenty years, the Aral Sea has lost a third of its surface area and two-thirds of its volume… The desert into which the former seabed has turned now measures three million hectares,” Kapuściński describes vividly.

Desert and silence

And it was this description of Muynak that captivated Joanna Kozuch so much that she decided to go there in 2008 with her then boyfriend and now husband, the prominent Slovak animator Boris Šima. “I really like travelling slowly. I’d rather see less, but I need time – that’s what I enjoy,” says Kozuch, who, as proof of her love of travel, named the animation studio she founded with her husband plackartnyj – after the typical long-distance trains so often seen in the countries of the former Soviet Union. Joanna and Boris say they first travelled to Uzbek cities such as Samarkand, which were very busy. “Then we found ourselves in Muynak, where it was suddenly extremely quiet. It blew me away. It’s a silence that is mainly in people… I love listening to the stories of the locals, and I love taking pictures of them too. I always ask them if I can. That first time I talked to them, but I didn’t take pictures – it didn’t seem appropriate at the time,” Joanna tells dok.revue. She left with the idea of making a film about the vanished sea in Muynak in which she wouldn’t use the faces of specific people. “I knew that the most powerful things often happen in the heads of the protagonists, so the surreal animation I love so much would be justified,” she recalls. Six years later, she went to Muynak again, this time alone. “I was really worried about whether the place had changed in that time, and I was surprised that it looked the same. But when I came to Uzbekistan for the third time, in 2018, everything had changed. In the meantime, the president had died, and Uzbekistan had opened up, but I think it’s mostly just superficial changes. It’s as if what happened to us in the wild ’90s is belatedly happening there now. Life is returning to Muynak because oil and gas reserves have been found at the bottom of the Aral Sea.”

Joanna was mostly interested in the local human stories. “It’s the story of a lost generation. When your welfare disappears overnight because the sea is gone, you just sit and stare into the distance and long for the water that isn’t there. Because this isn’t just the story of a huge environmental catastrophe – it’s also the story of ordinary people who have to endure the consequences of stupid and reckless political decisions every day.” The recklessness of leaders with regards to human lives unfortunately continues today, as we have witnessed fully since 24 February of this year. The film Once There Was a Sea is thus inadvertently relevant today.

A Slovak rarity

The director decided to tell the story of Muynak through the fates of four characters, whom she assembled from various narratives and faces, with supposedly only one character – the captain – resembling a specific person. Although Joanna Kozuch has been inclined to mix different styles and forms since the beginning of her work, this was the first time that she chose the genre of anidoc. “This genre interests me because I like to travel, and I can thus combine my two hobbies – animation and travel. Plus, I like reading journalistic literature,” explains the director. She also adds that she does not consider herself a documentary filmmaker. “I don’t have the courage to shoot on camera in these kinds of situations – I don’t even record interviews with people on an audio recorder. I just keep a diary every day during my travels, and I document my interviews with people from memory… The stories in the film are true, but the characters are not. It’s my painting of the Aral Sea. My Uzbekistan.”

Although in the Czech Republic we have several directors who focus on animated documentaries – for example Diana Cam Van Nguyen, Michaela Režová, and Magdalena Kvasničková – in Slovakia this is the first significant example of this format. Supposedly, when Kozuch submitted a grant for the film, there were comments that it was an innovative genre, although at that time anidocs were already a common feature at festivals around the world.

The short film was later joined by a longer version for TV because the Slovak public broadcaster RTVS automatically included the film in its documentary section, where filmmakers have to meet a mandatory length of 26 minutes. Joanna solved this issue by adding a story that shows Muynak’s transformation up to the present day, when life is returning to the town with the extraction of gas and oil.

A beautiful mishmash

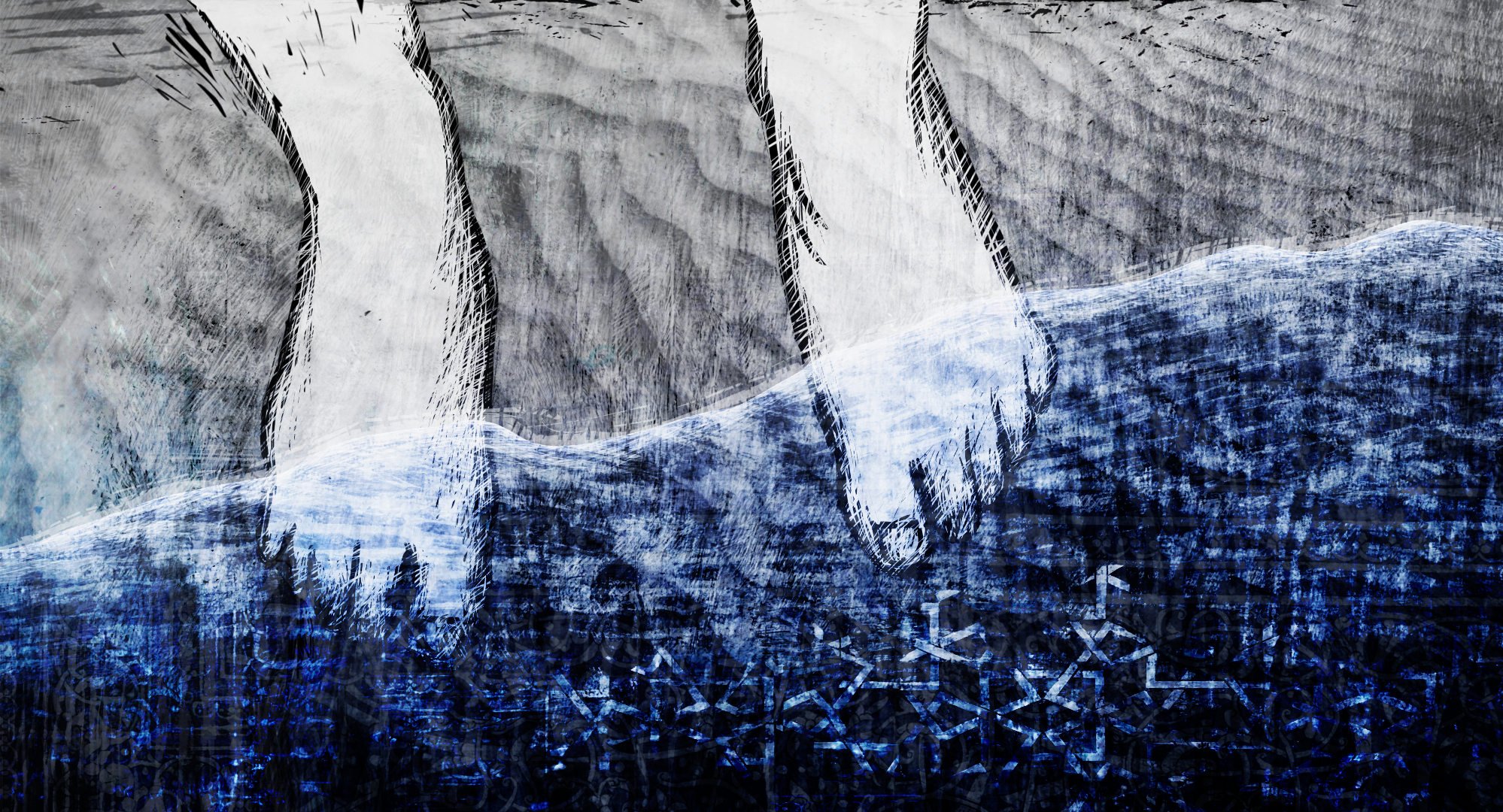

The visually impressive film does not conceal that its creator is also a painter. But the artistic aspect is not an end in itself; for example, the dominant blue is based on the prevailing colours of the ancient Uzbek cities, but it also symbolises the lost sea. “I like it when the art supports the story in some way. I based it on what I saw in Uzbekistan. That’s why I wanted to create a sea out of sand – I liked it as a metaphor for what happened to the sea,” adds Kozuch. The animator says she layered real photos, paintings, and animations of sand. “I also created linocuts – they were more structures than specific characters – from which I then made animations that I used repeatedly in the film. That’s kind of my way of mixing everything with everything,” the artist laughs, describing her entire oeuvre, which mixes different forms and styles but results in something that comes across as compact. In her films, fantasy mixes with reality and drawing with the pixilation of the actors or photographs of real places. This was also the case in Fongopolis (2014), a story about a violinist who is in a hurry to catch a train, but the train station makes things a little complicated for him. Kozuch received her first Sun in a Net Award for this short film. Her MA film Hra (The Game) also combines animation with actor pixilation, and 39 Weeks, 6 Days, a film she co-created with Boris Šima, presents a similarly unique mishmash of techniques in an intimate diary of her own pregnancy.

In addition to the film, the director is also preparing a website about the disappearing Aral Sea, which should be launched this summer. She says it won’t just be a regular website about the film, but it will also include scholarly texts on the historical and geographical aspects of the Aral Sea – and not only from the Uzbek side but also from the Kazakh side, where slightly different stories were written.

Refugees and Ukraine

At the moment, however, Joanna Kozuch already has new projects in mind. Originally, she planned to continue mapping similar humanitarian and environmental disasters and wanted to make a film about the Chernobyl tragedy. “When a catastrophe happens in a totalitarian state, in this case an environmental one, the attempt to cover up what happened causes another catastrophe that persists for the next thirty years. That struck me as a powerful theme,” adds Kozuch, sighing that it’s not likely she’ll make it to Ukraine any time soon. So she turned to a no less topical issue – a film about rubbish collectors on beaches. Rubbish isn’t the right word; it is the things left on the beach after refugees from the Middle East and Africa arrived there seeking refuge in Europe. “It came to me when I read three sentences about beach cleaners in a book. Then the first wave of refugees arrived, and my native Poland voted against the relocation of asylum-seekers throughout Europe. What’s more, we now have refugees on the Polish-Belarusian border who are being treated inhumanely by the Polish government. However, my film will be about an island in the sea,” elaborates the director, who, in my opinion, is absolutely unique in the Czech-Slovak milieu in the way she combines topical issues and social activism with an artistically refined and unmistakable style.