The Philippines: Thousands of Islands, Thousands of Positions and Themes of Documentary Film

The following text introduces the concept of the retrospective of Philippine documentary cinema that was presented at this year’s festival in Ji.hlava, which was the largest showcase of Philippine documentaries in Europe to date. How did festival programmers Andrea Slováková and Adriana Belešová prepare the entire retrospective, why was it necessary to visit the Philippines in person, and how did documentary film develop in the Philippines? Iveta Černá then gives an overview of the problems plaguing Philippine society today and how this was reflected in the programme of this year’s Inspiration Forum, which is the yearly discussion platform of the Ji.hlava International Documentary Film Festival.

How did the idea to organise a retrospective of Philippine documentary cinema at the Ji.hlava festival come about?

Andrea Slováková (AS): It’s part of the festival section Transparent Landscapes, where we present retrospectives focusing on specific countries and attempt to portray to the audience the way that documentary film has developed there from the beginning of cinema to the present. We’ve had a lot of these retrospectives at Ji.hlava; from recent years I can mention, for example, Taiwan or South Korea from Asian cinema and Iceland from European cinema. We chose the Philippines because we want to explore cinema that is lesser known or difficult to grasp in Europe – and also because they don’t have a very developed cinema infrastructure, so they lack the kind of systemic support for film production and distribution that we know from the European or American contexts or the kind found in Asian countries with tiger economies that invest more into culture. It’s usually the case in these little-known or more difficult to map cinemas that only a few filmmakers ever rise to prominence, and they are discovered through major European or American film festivals. This can be seen in the example of Thai cinema, from which the work of Apichatpong Weerasethakul is well-known around the world and in this country. But what else do we know of Thai cinema? Very little, actually. And what do we know of the country’s documentary cinema? Even less. That’s why we’ve started to focus on these territories as well, even with how difficult it is to prepare such a retrospective due to the fact that these countries have no functional or flexible institutions and for long periods of history there was no method of archiving films there, so some phases of the development of cinema are completely missing from the archives, especially from the first half of the twentieth century, during which many Asian countries were under colonial rule.

While not a lot is known about Philippine documentary cinema in this country, the Ji.hlava festival has been following the work of certain Filipino filmmakers for some time already. I am thinking, for example, of Khavn or Lav Diaz. Will their work be presented at the festival?

AS: Yes, some Filipino names have been reverberating at major European festivals as well as at Ji.hlava for a fairly long time. We are familiar with the work of Lav Diaz or the artist, musician, and filmmaker who calls himself Khavn, whose work we have been following at Ji.hlava for a long time. Audiences will also be familiar with the name of Kidlat Tahimik, whose comprehensive oeuvre was shown for the first time in Europe at Ji.hlava. Nevertheless, most of the names that will be presented in our retrospective this year are unknown – and not only in the Czech context. Many of them are being screened for the first time in Europe or anywhere outside of the Philippines.

Adriana Belešová (AB): In our retrospective, we will also be presenting works by some Filipino directors already known in Europe, such as Lav Diaz, Ishmael Bernal, or Jet Leyco. We will be showing, for example, Khavn’s film Overdosed Nightmare, which has not yet been screened outside of Manila.

In preparation for this retrospective, your team made a trip to Manila. Why was it necessary for you to visit the Philippines in person?

AS: It’s part of our long-term approach to programming. We cultivate an active programme, meaning we don’t simply pick through what has already been screened in the Western discourse. We truly care about learning what’s crucial in a given country, even in relation to its local context. In areas where the infrastructure is not as comprehensive, you don’t have a chance to discover certain things just by reading about the subject or watching films that you can access remotely. In these countries, you always have to get into the film archive and also watch old films that often haven’t been digitised. In the case of the Philippines, however, this was not a major goal of our trip as the Philippine film archive unfortunately has very small collections. It was established relatively late, and the country’s archiving policy took a very long time to form, so some periods are completely missing from the archive, and furthermore, the film prints are in very poor condition. Another interesting aspect is the repatriation policy of archives in Asian countries that were under colonial rule in the first half of the twentieth century. Some older Philippine films may even be present in Western archives. There was a similar situation in South Korea, where films from the early twentieth century could be found, for example, in Japanese archives or, in short, wherever archives even existed at that time. What’s more, the Philippine archive has a staff of about six people, and they have received film prints in absolutely disastrous condition, so their primary task is to protect and care for these prints. They then have no energy left to search for copies of Philippine films from the first half of the twentieth century, the time of colonial rule.

But our trip was also important because we visited different institutions and film schools, met with local filmmakers, and also got in touch with local experts. One key figure for us was Nick Deocampo, one of the most important film historians of Asian documentary cinema. He covers the entire region, but Philippine film is what he has researched and published on the most. Our dialogue with him was crucial to our work because as we researched the history and positions of Philippine documentary cinema, more and more specific questions came up, and Nick Deocampo was able to answer virtually all of them. Moreover, he guided us on who to approach next in the Philippines. For example, thanks to visiting in person, we discovered that over the past 15 years or so, regional cinema has become a distinct phenomenon in the Philippines. The country is made up of 7641 islands, and in addition to the two official languages, 127 languages are spoken there. This is also a strong determinant for the cultural life of the Philippine Islands. Roughly 15 years ago, this regional cinema production began gaining strength, and through our meetings there, we were exposed to some of these films and filmmakers. While the films may be more amateurish in the way they are rendered, it is a socially significant phenomenon that we have also documented in our retrospective.

Nick Deocampo is not only a historian but also a filmmaker. This year at Ji.hlava, he will be personally presenting a part of his oeuvre. What kinds of films are these?

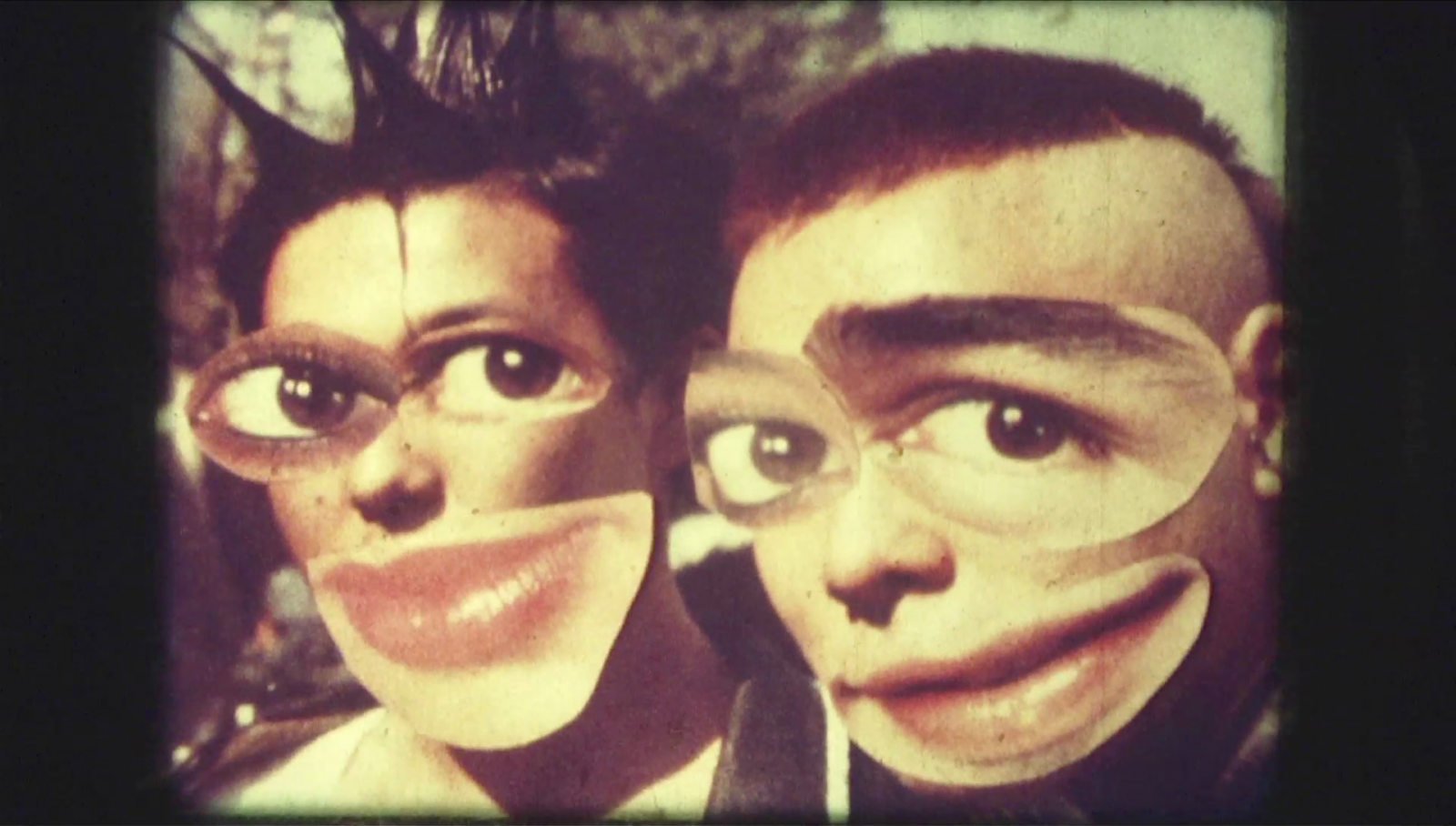

AS: In the 1980s, during the dictatorship and time of martial law in the Philippines, a vein of experimental documentary work developed which from today’s perspective we would label queer cinema. Deocampo was a part of this community. We will be screening, for example, his performative work Oliver (1983). During this time, several films were made in the Philippines that formally transcended the conventions of documentary film. Deocampo also made diary films and explored different documentary genres, and later, after 2000, he made several compilation films that relate to the history of Philippine cinema, but we did not include these in the retrospective.

Is a film’s formal innovativeness essential to your curatorial selection? What are your selection criteria?

AS: In retrospectives, we always try to show not only the way documentary film developed in the given region but also the evolution of the notion of what documentary film is and what functions it serves in that culture. That is why we include some experimental forms in our selection as well as more formally conventional films that convey important social themes.

AB: Our curatorial selection seeks more to highlight differences and diversity than to capture a kind of absolute totality of what is being made in the Philippines. For instance, we got access to some works that were made at universities. However, our selection can’t be comprehensive, and it doesn’t include, for example, mainstream works or those made specifically for TV. For example, some contemporary TV documentaries have such bold subject matter that our focus on the formal and artistic concept of the film gets a bit lost in them. With what we’re searching for, it’s important to find a figurative partner on the other side, and we have managed to collaborate with documentary producers and directors, educators from various film disciplines, and festival programmers and curators who are able to recognise our concept of documentary in its formal and stylistic diversity.

In the Ji.hlava retrospective, you are also presenting one particular gem, namely the 1913 film Native Life in the Philippines, which predates even Robert Flaherty’s legendary Nanook of the North, which is often cited as the first feature-length documentary in the world! Were you surprised by this discovery?

AS: The film Native Life in the Philippines is made up of five parts, which were released over time. According to historical sources, it appears that the separate parts were created with the aim of forming a whole. Therefore, it really is the first feature-length documentary in world cinema as it was made nine years before Flaherty’s Nanook. This was a surprise, because beforehand we knew about just one part of the film, and we only gradually learned that there were more. We think this is one of the discoveries that can enter the world film-historical discourse. It should be added that the Philippine film differs from Flaherty’s mainly in its dramaturgy, as it does not have a narrative structure based on a central story but is instead – more in correspondence with the form of short films at the dawn of cinema – a series of scenes depicting indigenous life.

AB: This film also illustrates the way cinema emerged in the Philippines. In fact, it shows one of the few positives of the first wave of colonisation, when the Americans filmed the indigenous population in the Philippines. In general, colonisation in the Philippines had a lot of ill effects because the colonisers didn’t allow Filipinos to develop their culture and identity. Moreover, the different cultures of the colonisers there – namely the Americans, the Spanish, and the Japanese – changed over the years, which had a significant impact on Filipinos. However, it was the colonisers who began to develop the local cinema there, teaching Filipinos to film and giving them the first cameras. This was crucial for the early development of Philippine cinema.

Czech audiences are more familiar with Philippine feature films than the country’s documentary cinema. We have had the opportunity to see films here by classic directors such as Brillante Mendoza and Lino Brocka. Is it possible to generalise whether the documentary position of Philippine cinema differs significantly from what we know from their local feature films?

AS: We deal with very diverse forms of documentary film, and we are, of course, also interested in hybrid positions such as docufiction. For example, Lav Diaz’s feature films usually employ a very spontaneous approach, work with improvisation, and contain long, observational, almost lyrical passages. So I was curious what the feature films from the 1950s and 1960s would look like as they were based on real events. Unfortunately, they look like Hollywood films – no hybridity. We only found one film that works with documentary elements, and that is Manila by Night (1980) by director Ishmael Bernal. The colonial influence is also apparent here because the beginnings of Philippine cinema were derived from the American studio system in terms of production while at the same time emulating the formal and genre conventions of Hollywood, which represented an imaginary ideal for local filmmakers. This is a phenomenon that has been described in the academic discourse, and Hollywood’s influence can even be seen, for example, in the work of the classic director Lino Brocka. In this context, it is then extremely interesting to look at documentary films because, while they also had various conventional forms, there was no single model or ideal to which filmmakers aspired.

AB: Colonisation has always had a certain influence on the development of Philippine cinematography, whether it was in the first half of the twentieth century or shortly after the Second World War. On the other hand, it’s important to say that from the 1970s, or rather the 1980s, a dictatorial regime was in power there, so documentaries and experimental films had to be made in a very underground way, and self-proclaimed directors such as Deocampo created films that could only be seen after the end of the regime, when they were also revised and evaluated. Like our former communist regime, the regime there at that time proclaimed that it had a free society and wanted to offer a peek into everyday life – thus in the Philippines a number of documentaries were made that seem almost absurd from today’s perspective. However, we don’t give space to these documentaries in our retrospective as they are products of their time.

Are there any films in your selection that reflect life under the dictatorship?

AB: We have some such films – for example by Mike De Leon or Nick Deocampo, whose 1987 film Revolutions Happen Like Refrains in a Song is journalistic in its filmed scenes and experimental in its post-production. I see in it a certain similarity to Czechoslovak documentaries from the late 1980s.

What guests have you invited to Jihlava as part of the retrospective of Philippine documentary film?

AB: We’ve managed to invite filmmakers representing various genres of documentary and experimental film – for example, the experimental artist Roxlee, who, together with his wife, will be on the jury of the festival’s experimental section Fascinations. We have also invited Lav Diaz and Khavn, who are planning a performative concert with an audiovisual accompaniment called The Brockas. And we mustn’t forget Nick Deocampo, who is to some extent the co-curator of our retrospective. We would like to invite more Filipino documentary filmmakers because, in contrast to the country’s feature films, Philippine documentary cinema is known only in Asia and not at all in Europe due to the geographical and cultural distance. For these filmmakers, this retrospective is a huge opportunity to showcase their films outside of Asia, and they see it as a great honour. This is one positive aspect of our efforts to raise the profile of lesser-known cinemas.

Which themes resonate most in Philippine society today?

Iveta Černá (IČ): We visited the Philippines in May 2022, shortly before the presidential election, so during our visit to the city, we saw various street blockades where events related to the presidential campaign were taking place, but at the same time the elections were stirring up the whole country because they were being held on all levels, from local councils to the senate. We also got a sense of how strict the rules were in the Philippines during the Covid pandemic. All the hallmarks of a political regime that is quite harsh towards its people were magnified during the pandemic, whether it was pressure on activists, arrests, or the war on drugs. The themes we saw on the streets were intertwined with those we learned about from our conversations with people in the filmmaking community or with people in the climate movement, which is connected with social dissent. Dissent there involves various groups of people; it can be leftists or environmental activists, representatives of minorities or indigenous communities from different regions, or religious minorities – especially Muslims. At the time we were there, the so-called war on drugs was also ongoing. Started by former President Rodrigo Duterte, it is a brutal campaign, in his words, against drugs, but in reality, he extrajudicially executed between ten and twenty thousand Filipino citizens, mainly from the poorer classes. It has had a large impact on the development of society; for example, many children have been left parentless. One case resonated particularly strongly in Philippine society, in which a young activist from an organisation that helps the poor in a Manila slum was arrested for allegedly possessing weapons and then gave birth to a child in prison, who was taken from her and subsequently died. Such cases are commonplace in the Philippines; they resonate with society, and some people take to the streets to protest. Nevertheless, the election that was taking place during our visit was won by Bongbong Marcos, son of the former dictator. His father, Ferdinand Marcos, who ruled the Philippines from the mid-1960s to the mid-1980s, imposed martial law, brutally suppressed all dissent, and then made off with a huge fortune when he fled the country. For the past few years, however, there has been a campaign in the Philippine press and especially on social media to rehabilitate the Marcos family. In this year’s elections, Bongbong Marcos defeated Leni Robredo, the former vice-president and an implacable critic of the war on drugs who wanted to tackle the problem as a social issue rather than a security one. So, the question now is whether Marcos will follow in the footsteps of his father’s previous regime.

How are contemporary issues in Philippine society reflected in the programme of this year’s Inspiration Forum, one of the key accompanying programmes of the Ji.hlava Film Festival, which offers meetings and debates with inspiring figures on key topics of the day?

IČ: In the scope of a day that will be dedicated to freedoms that often remain only on paper, even in our European context, we will welcome Filipina artist Kiri Dalena, who is originally more of a documentary filmmaker and political activist and whose art is deeply tied to political protest and focuses both on the past dictatorship and what is happening now.

Another important topic is the impact of climate change as the Philippines is the fourth most vulnerable country in the world in terms of its effects, primarily due to its location. A significant manifestation of climate change in this region is the increase in the intensity and number of typhoons, which has an impact in particular on the countryside, where there is a risk of landslides or floods. The Philippines is, of course, not one of the main producers of CO2, and what’s more, the whole of Southeast Asia is suffering from deforestation at the hands of companies with owners in the West. The deforested landscapes are then less able to cope with floods or typhoons, and instead of forests, large Western companies want to plant oil palms, which is also transforming the entire landscape. The Philippines is an interesting example of how the climate crisis is an economic problem and how its solution hinges on a transformation of the economic system. This is what we want to address more at this year’s Inspiration Forum through the theme of degrowth, the concept of which emphasises quality of life indicators other than economic ones, thus highlighting the importance of social justice and environmental considerations. So, in a way, our trip to the Philippines inspired the programme of this year’s Inspiration Forum.

AB: In recent years, the life of the country has begun to intertwine with the topics of documentary filmmaking there. Although documentary filmmakers in the Philippines are more experimental, they also deal with current issues. The retrospective in Jihlava presents, for example, Jet Leyco’s experimental film Two Way Jesus, which highlights the popularity of the Easter holiday, during which some people in the Philippines actually have themselves crucified on Good Friday but which at the same time has become a spectacle full of alcohol and commercialism. Dominant themes in contemporary Philippine documentary cinema include poverty, the situation of today’s families, the security of the elderly, and the upbringing of children, while city life versus life in more remote parts of the country is also a common topic. I also frequently encountered depictions of arrivals in the city, for example On the Way to India Consciousness, I Reached China from 1987, which we will also be screening at Ji.hlava.

Although Philippine society has many problems, it is, largely thanks to the American colonisation, very visual and saturated by advertising and audiovisual content, which is to a great extent reflected in the country’s films. It’s a kind of meta tool for transforming visual smog or mainstream visual culture into – from our perspective – a higher art form. From their perspective, however, it is not so much an attempt at art but rather the use of a tool that can engage a wider audience expose them to certain topics.

In the Philippines I met both with committed independent filmmakers who create art on a shoestring budget and with representatives of large TV productions that are screened at festivals around the world such as Sundance or Toronto, get broadcast on major networks like CNN, and have producers who are experienced with foreign co-productions. In this regard, there are big differences. Even the films we didn’t select for our Ji.hlava retrospective are important. They deal with pressing issues such as the abduction of women and emissions allowance trading, but they conform to the style of American TV production. For example, these producers invited me out for a drink in the most expensive neighbourhood in Manila, meanwhile we were staying in an old neighbourhood where people keep roosters in cages and take them to fights. It’s a world of great contrasts.

IČ: It should be added that we only stayed in Manila, but in the Philippines there is a big difference between the capital and the rest of the country. This also shows in their cinema: films are being made even outside of Manila, but they are more amateur productions because of the lack of facilities.

AB: The lack of facilities can also be seen in their restoration and preservation of films. They store films in plastic bags on the balcony. Still, I got the beautiful feeling that even with so little, everyone is trying to do great things. But now I sense that they are undergoing a big change, and the financial angle and mainstream production for the masses is slowly starting to take over at the expense of independent production.

What was the most memorable thing about your visit to the Philippines?

IČ: The thing that stuck with me most is the lack of infrastructure. There were constant traffic jams in Manila, and it often took us two hours just to get to a meeting, which is supposedly normal there, and many people commute to work like that every day. It’s one huge conglomeration. They also acutely feel the impacts of climate change, even in Manila, where every major typhoon is followed by flooding, so people routinely have water on the ground floor of their flats or universities, and they walk the streets waist-deep in water. The Philippines started thinking about making changes due to global warming quite early on, pushing through the Climate Change Acts in 2009, but at the same time, implementing these things is much harder there. In contrast to Europe, there’s also a big difference in the essence of the legislation. While the goal in Europe is ecological transformation and carbon neutrality, in the Philippines the regulations focus primarily on reducing the risk of the impacts of natural disasters. The way that social debate and activism differ there was also interesting to me. In Europe the climate debate is linked to lifestyle choices such as shopping in second hand stores or limiting meat consumption, air travel, and single-use plastics, but for Filipinos the fight against climate change is about helping communities affected by disasters or fighting to stop the construction of coal-fired power plants near their homes. On top of that, of course, the notion of climate justice resonates throughout the entire Southeast Asian region. Even among representatives of the local climate movement, there is a sentiment that the region has not contributed as much to climate change as the Western world and should therefore be allowed to continue its economic development.

AB: What surprised me most was how extremely complaisant and flexible Filipinos are. Most would rather follow certain patterns of society than go against them. I’m not saying that submissiveness is always a bad thing, but I see it as a characteristic of the entire society there. I saw it in the hotel and on the streets. It was almost unpleasant – I felt like I was inadvertently starting to take advantage of them.

IČ: And that complaisance also inscribes itself on the country’s economy. There has been a large emigration of Filipinos to all over the world, especially North America and the Persian Gulf, where Filipina women in particular work as housekeepers or nurses. The money they send back home makes up roughly ten percent of the Philippines’ GDP. It even has an impact on children’s upbringing and the family as such because children then grow up without their mothers. We were surprised at how early people start living an active working life there. What struck me, however, was the massiveness that we saw at every turn in overcrowded Manila; in the subway, for example, there are several checks before you board the train, and the inspector may shout at you if you are talking to someone. When there’s that many people, you stay in line and do as you’re told. And you don’t deviate.

AS: I perceived a conflict between a certain scepticism or even resignation regarding the possibility of people influencing the governance of the country or the broader political configuration, which we could observe in the context of the upcoming presidential election, and a struggle for identity, or rather an enormous desire for and search for ways of expressing one’s own identity in art and film. Queer cinema already existed there in the 1980s in spite of the authoritarian regime, and after a wave of distinctive filmmakers who identified with American models of cinematic conventions, many filmmakers emerged, including a few women filmmakers, who suddenly wanted to transform the modes of viewing the reality they lived in and wanted to loudly name the issues that were weighing on their communities or society.