O Futebol: Constructing the Film Reality

O Futebol, a film by Sergio Oksman, a Brazilian-born documentarian and experimenter based in Spain, (un)intentionally captures the last month in the life of the director’s father. In 2012, the winner of the grand prix at Karlovy Vary IFF for his previous short montage film called A Story for the Modlins returns to his native São Paulo in his new film, O Futebol. Through a focused observation he presents the memories and the story of his father – an ordinary labourer and a football fan – in a (literally) break-neck World Cup deadline. The film had a triumphant premiere at this year’s Locarno and also in Seville and at the Portuguese Doclisboa festival.

Following the fictitious playful portrait of the Modlins, your latest film sets off in a seemingly different direction. O Futebol, your first feature-length film after almost a decade, is remarkable for its distinct, almost strictly principled concept based on the method of silent observation. Was this your original approach in the early stages of the film’s preparation?

My aim was to work with limited material, on several levels. On the one hand, you have the city that plays a crucial role in the film: São Paulo as a centre with its own unique reality and in the film, it, in fact, serves as the only element that does not give in to my construction. Everything else is naturally just my construction, there is no line between reality and artificiality. I had an entire plan drawn up from the start. The film will have a single protagonist and his life, and a unified space, in which we meet.

Your intent was to create a layout stemming from classical Aristotelian principles: unity of the place, events and also, as you specify in the opening part, the time span?

The film unfolds within the time frame of a single month: like a calendar of the football cup, in which Brazil lost, as you know. And my father had predicted this result – as you can see in the film, he is sitting in front of a TV set and says that Brazil will only make it to the semi-finals, but can’t stand a chance as a winner. And that’s a fact – nobody has ever known as much about football as my father, as he himself liked to say. He spent his entire life watching football…

Before depicting the events from June of last year, you as the narrator-director meet your father at the entrance to the stadium and tell him about your plan. You hadn’t seen your farther for twenty years. Did your “film reunion” actually happen or was it only staged for the purposes of the film?

It did happen. We met in 2013 and talked briefly. In the film, there is only one scene showing this meeting, but it is a key scene because it works as a kick-off for what follows. We are standing at the gate to the terraces, almost a touch away from the soccer game, so to speak, but you will not see live football game in the film. Instead – it starts raining, suddenly and heavily! You simply can’t plan and control everything… I had a ten-point script for the film, ten principles like in the Testament, guidelines for my shooting, which I followed very strictly. When filming my father at work, the camera had a firmly specified position, from which it observed “figures” in a car in the scenes where I appear. That way, we have set the limits of what we will not be showing in the film. Football only provided a clear layout for this concept: the game has a rectangular field divided into two parts and with two teams playing in the field that compete with each other, and the only thing you know is that it takes ninety minutes. But nobody knows what will happen during the game. And that was exactly the case of my father.

O Futebol

It is remarkable that you did not wrap the project up after your father’s unexpected death.

It did not have any impact whatsoever on the film’s dispositive. At the moment, when my dad was taken to the hospital, I continued in line with my Testament, which did not rule out such a situation. I continued shooting, day by day. Maybe you know a diary entry written by Kafka in 1914: “Germany declared war on Russia today. Afternoon: I went to the swimming pool.” This is what I wanted to do too: to juxtapose big and rather insignificant events that occur at the same time.

How did you personally cope with the situation, away from the camera?

We had made a father-son pact that I was supposed to follow. And so I captured my father’s last days. And it was only after the premiere when I saw the film more objectively and realised that the figure of the son was actually me. And this is the essence of the dichotomy of a director and the protagonist whom I portray in the film. O Futebol was actually conceived as a fiction – it was edited like a fiction film and worked with the main protagonists like a fiction film. It is a two-level structure: one story focuses on the death of a father and the way in which his son copes with it. And on the second level I had to figure out how to finish the film from the position of a director.

Why did you choose such a personal topic – a reunion with your father? Did you (in)directly deal with something unresolved, something fleeting in your story? Your film doesn’t explain why you lost touch with your father after you moved to the other side of the ocean, to Europe. More remains hidden than revealed.

Although I was making a film with my father, it wasn’t supposed to be a therapy. I feel respect to films whose aim is to serve as a therapy, but this wasn’t my goal. By the way, festivals are nowadays plagued with the epidemic of film portraits, of personal films – which, on the one hand, is understandable, but it also has its pitfalls. My plan was absolutely simple: to meet my father and to watch the championship in his country. Because we have never done anything like that. And just like that, to spend time – with someone else, isn’t that awesome? Especially when the person is your father. We did what we could have done thirty years ago, if we hadn’t lost each other. And this, as it turned out, was the last chance.

Did you know about your father’s health issues?

No, my father hadn’t been ill at all. The end came out of the blue.

Do you believe in fate? As if you, perhaps subconsciously, generated such a situation through the presence of the camera and the power of the film. As if you as a director, the “mournful god of this story”, as Milan Kundera would put it, gave the fate a dramatic push. Do you feel the same during the screenings of your film?

I don’t think that the film actually contributed to his death, I wasn’t aware of his condition. Indeed, it is strange that it happened when I was shooting the film, it is very, very mysterious. I had a clear idea of how to end the film: I will take my father to the airport, regardless of the result of the World Cup, and leave the camera with him. Then I will depart. Indeed, we never shot this scene. So let’s not talk about fate, I could only control the events and I tried to control the entire shooting. But you cannot control death, rain and the fact that the clock in the car suddenly stops. It is a fiction film – it was shot and under control – but this fiction has reality at its core.

O Futebol

Do you distinguish between the “genres” of fiction and reality? The film was featured in the main competition in Locarno, and it was also presented at Doclisboa which is known as a documentary film festival. What is your perception of the borderline between fiction and reality?

I’m always happy when my films – for instance the Modlins – are presented as documentary works, at the same time being included in the short fiction competition. There’s no objective position to take – you can’t label the film as a pure documentary work, because that’s your subjective angle. I graduated in journalism: objectivity does not exist. And you know what happened when I was in Locarno with my film and what made me very happy? One of the viewers at the screening objected that the part of my father was played by an actor! No, it was my dad, who actually died in the film. No-one can play my father better than himself.

Considering that you approach O Futebol partially as fiction and partially as a documentary film – was your effort to make it a genre-specific film (football thriller, family film, and in the end mainly the fatal topic of departure and coping…) more apparent also during editing?

I wasn’t interested in genres. But I wanted to leave all the possibilities open – you can call it genres, perhaps the genre of Argentinian romantic soap-opera… That’s an exaggeration. First of all, what I, as the film’s author, see as the most important thing is the decision-making act that actually consisted in determining the form and method of shooting, the decalogue. My father was to be followed by the camera, but free of any pressure, he was always allowed enough space to escape, to disappear away from its field of vision. And the frequent scenes of our conversation in the car were also a logical choice: it is the only intimate space where we could be honest to each other, speak in privacy. I will unveil another great mystery in my decalogue: it had a heading that said: “Parting”. And really, when I watch the film on the screen, it seems as if death was sitting at the backseat of our car – and it is death that watches us from the position of a viewer, waiting in silence. But it is already present.

Just like in your film, an identical layout for the combination of football and the father/son relationship is used in the film The Second Game (2014) made by one of the masters of contemporary Romanian New Wave, Corneliu Porumboiu: his spontaneous conversation with the father-football referee is visually complemented with a found TV footage collage of a derby between Steaua and Dinamo Buchurest from 1988. When comparing these two, both films seem to be mirroring two potential, purely contemporary approaches to the borderline (non)fictional concept. How did students at the Madrid school where you are a lecturer respond to your “construction” strategy?

They haven’t seen the film yet because its premiere in Spain is scheduled for November. When thinking about what method to use, I didn’t have lecturing in mind, my aim wasn’t to “showcase” some standards or some possibilities. Corneliu Porumboiu’s film also doesn’t serve as a “model”. Each of us construed our films in our own way. I agree that they have much in common – but none of them shows a live football game, in The Second Game you can only see an archival footage of a snow-covered field. Moreover, we don’t see both of the actors, we can only hear their voices. His idea is brilliant – wow, I said to myself when I was watching the film – this concept is so functional and fantastic! And since they don’t talk about football, they talk about the past, Ceaușescu’s regime, and their mutual relationship. Mine is the rain, and Corneliu has snow.

|

|

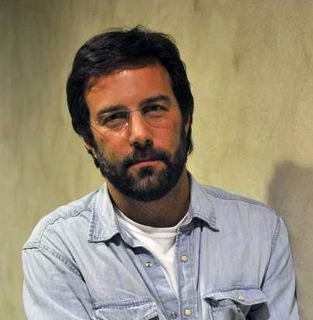

Sergio Oksman (1970, São Paulo) graduated in journalism in Brazil and subsequently completed film directing studies in New York. Since the 1990s, he has been living in Spain, where he currently lectures at the Madrid Film Academy, ECAM. He is the founder of Dok Films, with which he is also making his own creative documentaries often following a strict concept of film investigation into a personal or imaginary history. His mid-length films Notes on the Other (2007) and A Story for the Modlins (2012) were successfully presented at the Karlovy Vary IDFF. Aside from feature-length documentaries A Esteticista (2005) and Goodbye, America (2007), he often collaborated with TV stations and many projects were dedicated to the world of football (Ronaldo: Manual de Vôo, 1998, Benfica na Memória, 2004, and the series, El partido del siglo, 1999-2000). |