Like the dog on the beach...

I first met Karel Vachek in 2000. A foreign student at FAMU, fascinated by the Prague Spring, I had watched Elective Affinities (Spřízněni volbou, 1968), Vachek’s chronicle of the 1968 presidential elections in Czechoslovakia. I made a film about him, an awkward student production that Vachek patiently tolerated, and two years later, I brought him and his post-1989 “film novels” to the United States. On this tour, and another one seven years later, we walked through a New York very different from the city he’d known in his difficult years of exile. He taught filmmaking to my students. In late winter on a rocky Rhode Island beach, he smoked his trademark hand-carved pipe, and ordered our family dog to retrieve a duck for him.

I was fairly starstruck by it all. Here was this major figure in the Czechoslovak New Wave, the head of FAMU’s documentary department, a director whose shortest recent film was longer than three hours, but his office door at FAMU was almost always open. A trail of pipe smoke was the telltale sign, the students and colleagues drifting in and out. When I asked him for an interview, for permission to use one of his films in a DVD, if he wouldn’t mind company as he walked to a used record shop, the response was always the same: to víte, že jo. Of course.

Vachek was devoted to his students, his colleagues, his collaborators. But I think that wasn’t the only reason why he found time for all of us. From his March 1965 segment of the Army Newsreel (Armádní filmový měsíčník), to Elective Affinities, to the work he made later in life, when he was making up for lost time, his films are, perhaps more than anything else, collections of people. So are his paintings: bright, wall-sized, intricately geometric constellations of individuals who were the lodestars of Vachek’s personal philosophy. So, too, the office hours and the weekly “open seminar,” a class whose topic wasn’t exactly film. Instead, Vachek would stage a conversation—usually as provocative as the ones in his films—with someone in politics, culture, public life. Sometimes he just played records (Trini Lopez, Woody Guthrie); those weeks, a piece of paper would be pinned to the classroom info board with the word “DISCOTHEQUE”.

If you’ve seen Vachek’s films, you know that they are not “documentaries” in the usual sense of the word. I remember a chance meeting between him and Jonas Mekas at Anthology Film Archives in 2002. Vachek had just introduced one of his films, and as we were walking out, suddenly, there was Mekas with a glass of wine, and there was Vachek with his pipe, and these two towering figures in East European nonfiction film didn’t have very much to say to one another. Of course they didn’t. They were different generations: Mekas’s shaped by the war, Vachek’s born into it, and as émigrés in New York, their experiences were wildly different. Vachek struggled to find work, let alone make films, and returned to Czechoslovakia—where, like many of his generation, he had been forced into manual labor after 1968—in 1984; Mekas became the catalyst for much of what happened in the American avant-garde from the 1950s onward. But it was more than that. From the beginning of his career, Vachek put little stake in the idea that films could chronicle the world in the way Mekas’s diary films did. This is the very point of his FAMU thesis film Moravian Hellas (Moravská Hellas, 1963), in which he equipped the Saudek brothers with a Nagra and a microphone and sent them to the Strážnice folk festival to send up the idea of cinéma vérité. Nevertheless, Vachek is no less personally present in his films than Mekas is in his, on screen, as in the classroom and elsewhere, bent over his pipe, thinking, arguing, often acting—always directing.

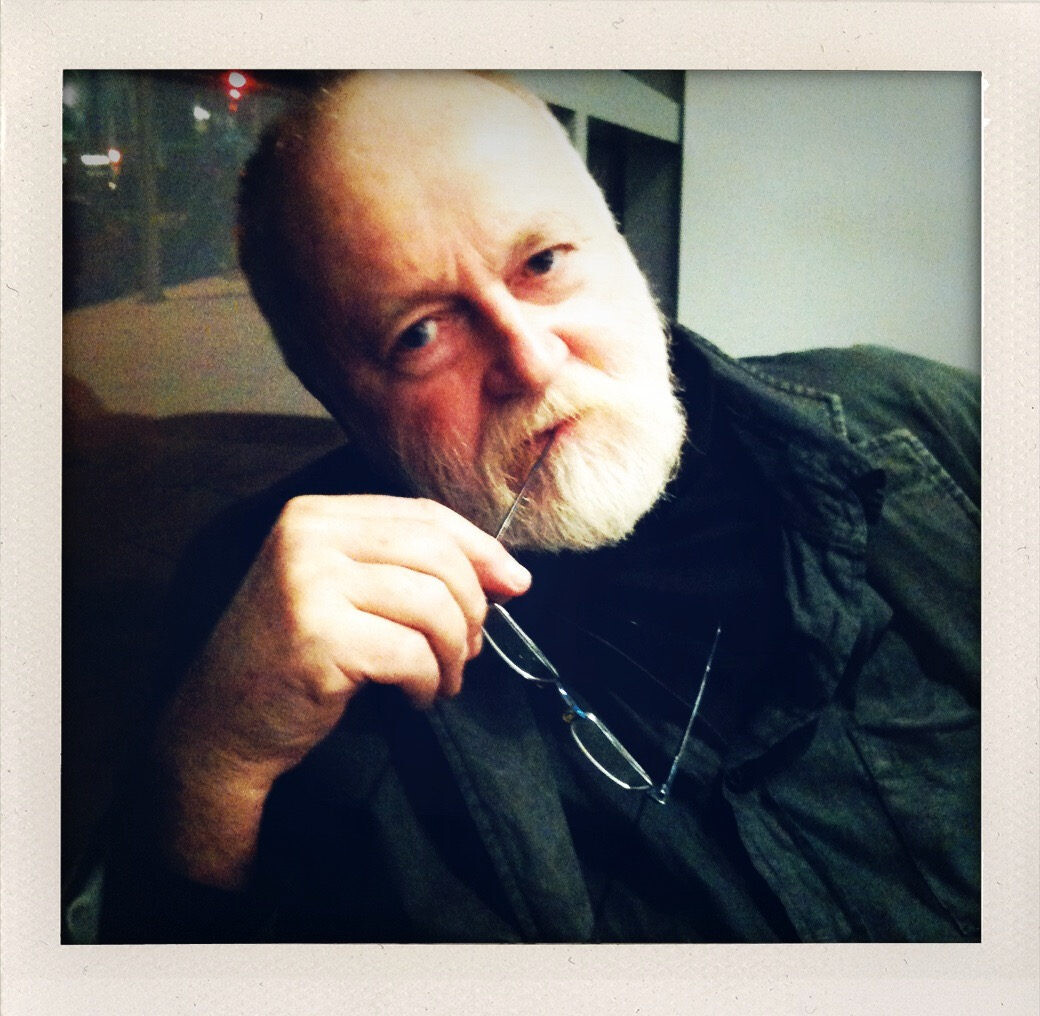

Karel Vachek in his film Communism and the Net or The End of Representative Democracy (2019). Photo: Ji.hlava IDFF.

We didn’t always know it. Or at least I didn’t, until we were in a crowded screening room in upstate New York in 2009. Vachek was introducing Moravian Hellas, and I was interpreting for him. He used a word whose equivalent can sound offensive in English, and so I translated around it. Vachek stopped talking, looked at me, and said sharply, Alice, přeložte to. Alice, translate it. His English, I realized then, was better than he’d ever let on—and there I was, like the characters in his films, like the guests in the seminar, like the dog on the beach, being (unwittingly) directed.

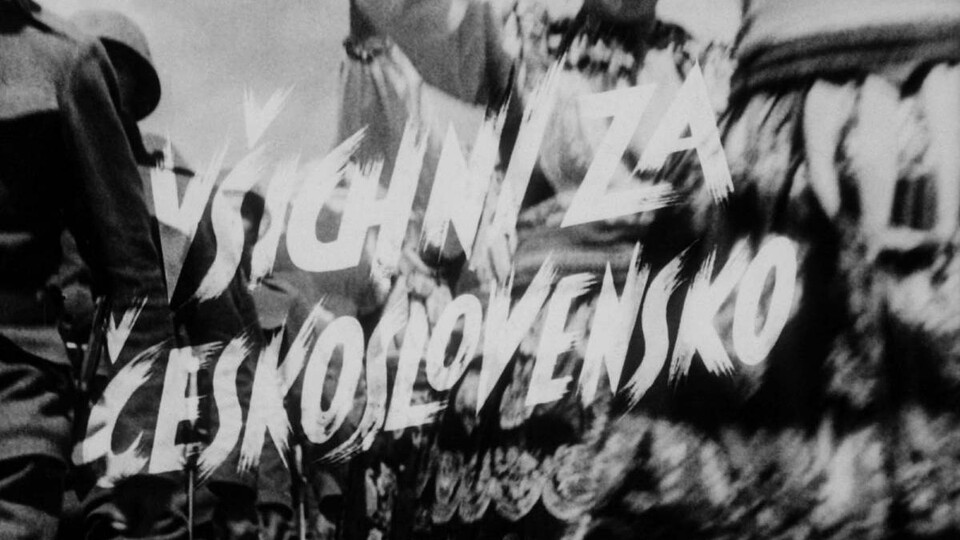

Vachek and I lost touch over the past couple of years. But I thought of him this January, when Trump supporters stormed the U.S. Capitol in Washington, DC. Insurgents had surrounded a pile of Associated Press cameras, tripods, and sound equipment, which they were kicking, smashing, attempting to burn. Years ago, Vachek had told me a story about filming during the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968, and of a Soviet soldier taking his camera, opening it, unspooling the film, and peering at the strip as the images he sought there were exposed into oblivion.

Whether or not it was true, it was the kind of story Vachek would tell. Even if the footage had been developed, he might have said, it would have amounted to just pictures—neither truth and evidence nor fake news. And the hapless Soviet soldier, unschooled in photography, would have been very much at home in Vachek’s films, which were populated as much by pitiable innocents and holy fools as they were by prophets and misunderstood geniuses. But the image of Vachek on the streets of Prague during the invasion is also one of his devotion to the promise and energy of 1968, a devotion that persisted into our dystopian present. In exposing the weirdness of the world, after all, he also hoped to make it better. And for many of us, he did.