It Was the Difficulty of Being There

It took only 6 months (March to September 2016) for Greek filmmaker Maria Kourkouta (MK) and Greek writer Niki Giannari (NG) to finish their film, Spectres Are Haunting Europe. They captured the situation and atmosphere in the Idomeni refugee camp located on the border with Macedonia. As they say, their primary motivation was not to shoot a movie focusing on migration. They just started shooting the surroundings during their location scouting for a different movie inspired by the Greek civil war in 1940s. Read more about the natural development of the Best World Documentary Film from the 20th IDFF Jihlava in the interview below.

Where did the idea to shoot this documentary film come from?

MK: The original idea came during the first shoot, since there had been no prior plan to make a film. Speaking more broadly, the idea to make a film came from the need to find images and rhythms going deep into the history which has left traces on the present state of things - if one is ready to look for them. The documentary form can be one of the ways to do this…

Where did you draw inspiration for the way you approached your documentary film?

MK: When the film’s co-director, Niki Giannari, and other friends from the Social Clinic of Solidarity of Thessaloniki brought me to Idomeni for the first time, I felt as if I were on the set of The Suspended Step of the Stork by Theo Angelopoulos, which was shot in 1991. In a certain way, this prophetic and poetic film, which treats the subject of boundaries and was shot at the border, served as a source of inspiration for us, especially during the colour-correction stage, inasmuch as his film makes dramatic and rhythmic use of colour, or, rather, of greyness. During the shoot, I also thought a lot about the compositions by a filmmaker friend, Philippe Cote, and his film Va regarde II. As for the editing, another friend, editor and filmmaker Qutaiba Barhamji, greatly helped and inspired me with his point of view on the Syrian people and, generally speaking, on cinema.

Collaboration between a filmmaker and a writer is not very common in documentary filmmaking. Where did you meet and how did you start to collaborate on the film with Niki Giannari?

MK: We have shared a deep friendship for more than fifteen years. So it was rather obvious for us to work together on this film, especially since it was Niki who had insisted so much that I go to Idomeni to film. I know that collaboration with a writer is unusual in the realm of documentary film. But, at the same time, there is no script underlying the editing choices, and there is definitely no linear narrative. The film unravels more like a poem, if I may say, than a narrative in the traditional sense of the word, which is also unusual for a documentary. This “poem” is, without a doubt, the result of a profound exchange between the two of us on the ways we have experienced and felt the things that we saw there together.

NG: As for the text that I have written for the film and that we hear at the end, it emerged from the images themselves when I saw them shortly after the shoot at the first screening of the rushes.

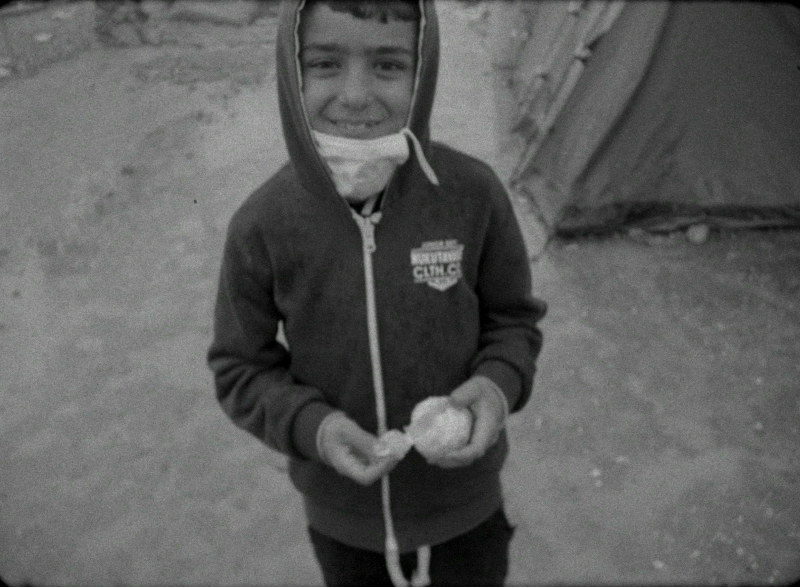

Spectres Are Haunting Europe (Maria Kourkouta, Niki Giannari, 2016)

Why did you choose this “hot topic” of the migration crisis for your first feature-length documentary? What was the reason?

MK: Our goal was not to make a film on a “hot” topic, but to create images that would automatically enter into a dialogue with “burning” images — of the past as well as of the future. Making a topical film can be dangerous for two reasons: on one hand, the film may unknowingly subordinate itself to the dominant reading of current events, while also serving as a moral alibi in one’s relation to what’s happening. On the other hand, to make such a film means to make something very commonplace, since many people are working on this subject — fortunately.

NG: Another reason was our shared feeling that we, in the sense of the Greek and European society, look at these people, these migrants, without really seeing them. We have become so used to considering them as foreigners, as weaklings — and this is in the best-case scenario, from a humanitarian point of view. Our need was more political than humanitarian: to preserve a fraction of the things which are absent from journalistic images; to bear witness to a certain state of affairs within contemporary European history; to capture for eternity, before it disappears, an image of these people, of their feet or their little gestures in this long wait.

What was the biggest problem you had to deal with during the shooting?

MK: It was the difficulty of being there, of feeling, of exchanging thoughts, of touching, always by way of the camera.

NG: There was also a particularly difficult moment to experience and to shoot, which was the sudden departure of the migrants, their decision to cross the border illegally, in the afternoon of March 14, 2016. We see it in the first and last scenes of the film.

Spectres Are Haunting Europe (Maria Kourkouta, Niki Giannari, 2016)

How did you find your producer? Did you make an international co-production or self-production? Why?

MK. We met the film’s co-producer, Carine Chichkowsky, thanks to other filmmaker friends who work with her. Carine and I have worked together for more than three years on another film project. Carine graciously accepted to help with this film, even though it wasn’t planned. Still, we have taken upon ourselves a big part of the production expenses. But it wasn’t an “expensive” film. Sometimes it’s enough to work other jobs to earn a living, as long as one has recording equipment and good friends like André Fèvre, who always records sound for us, then just to go out and shoot.

Can you describe the development process a little bit? How did you write the treatment? Did Niki as a writer play an important role in this stage of making the movie?

MK: We didn’t have the idea or the time to write a treatment. We were in Greece to do location scouting for a project on the Greek civil war of the 1940s, and we found ourselves filming people who were escaping a different civil war, today. This was in March 2016. The film was finalised in September 2016, after several months of very intense, continuous work. We had found, articulated and put in place the film’s aesthetic during the shoot, and then defined the treatment during editing. At every step, we were in constant dialogue, so Niki played just as big of a role in the final product as I did.

Did you use a script or anything we can call script?

NG: There was no script in the traditional sense of the word. In a way, we began to write the “script” from the moment when we decided where to go and what to look at. If I may say so, the script was written with and by the form of the film.

What does the term “script” mean for you with respect to a documentary movie?

NG: The height of the camera’s position, the light, the composition, the use of digital or film, these are the elements which define the narrative style, since they obey to the vision of the filmmaker(s). This vision can intervene in or even distort, in a decisive way, what we call “real” in a documentary, and so it constitutes a kind of a script. The shooting and the editing are crucial stages in the construction of the story being told, and they don’t necessarily need a predefined script. But reality did impose itself on our point of view: the people who were waiting to cross the border of a closed Europe captured our gaze and guided it toward a certain aesthetic, and therefore also political, position. The more time passed, the more we thought and felt differently. The cinematic result embodies this process in its form, since the film changes course. This is what it means for us, the script in a documentary film: one’s aesthetic and political position in the face of recorded reality, at the very moment of recording, then during editing and other post-production stages.

Spectres Are Haunting Europe (Maria Kourkouta, Niki Giannari, 2016)

Why did you decide to leave the experimental form? When did you decide to use the very long and static shots? During development, or shooting or editing?

MK: In general, I believe that one has to choose an artistic form in the name of freedom, and not due to an attachment to a certain cinematic genre. Personally, I don’t have the impression of having abandoned the experimental form. I can express myself using one cinematographic form or another, when I feel that what I have to say or do needs a particular form of expression. This is a big question of how images are born within us, how we create others, and why we choose this or that form. What’s certain is that the form is, above all, linked to the cinematographic rhythm of a film, and the form also produces a rhythmic result. In this sense, for me, the rhythm is more important than the form. For this film, we chose to do single-shot sequences because we couldn’t think of another way to hold onto what we saw in front of us, and to stay within it. These long scenes were created during the shoot and then re-affirmed during the edit. When the film changes to black-and-white 16mm, the rhythm changes completely, which justifies what I said earlier about formal choices.

Did you show your film to your protagonists or people related to them? How did they react? Did they have any remarks?

NG: Unfortunately, we haven’t yet had the opportunity to show it to the people we filmed who, after Idomeni, have dispersed to different parts of Greece. For several months now, we have been searching, and we have found a few among them. We hope that soon there will be the right conditions to show them the film and to hear their remarks. In any case, we hope our film will be like a space of hospitality for these people to express themselves, even if, inevitably, the film gets our point of view across more than theirs. For this reason, we strongly feel that it’s just as urgent to give them the possibility to create their own films, and, above all, to live the life they want; this depends only on the strength of the hospitality that we can all provide, on our desires and on the battles that we wage so that a different politic will be applied in Europe, today.