Filmmaking is like a unique manuscript

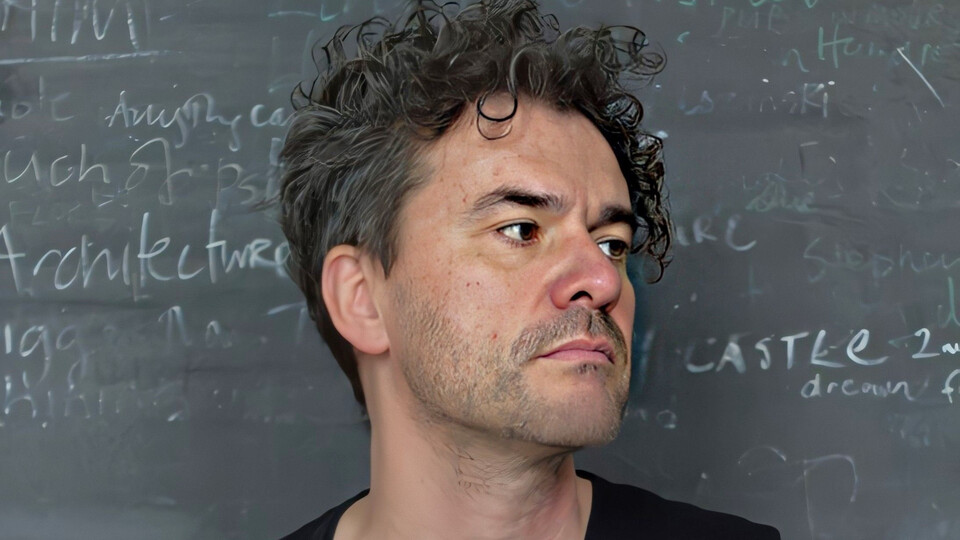

We talked about this year's Ji.hlava International Film Festival programme, focused viewing, the importance of retrospectives and experiencing the world differently with festival director Marek Hovorka, programme director Petr Kubica and experimental documentary programmer Andrea Slováková.

“Alongside the worlds that documentary filmmakers show us, there is the world of the artwork that we’re trying to nurture.”

In what ways are documentaries more powerful for you than fictional films?

Marek: For me they’re freer and more personal. They can respond more quickly to the changes in the world and allow you to think about it, not just experience it. Documentaries give me much more space when I watch them. I don't feel as pressured by the emotions flowing from the stories. That allows me to connect to specific characters, places or themes more naturally and experience the world differently.

Andrea: For me, no one type of film is exclusively stronger; the boundaries between them are permeable. What fascinates me about documentaries, though, is how they can often look at aspects of the lived world in ways I hadn't thought of – or rather, how they can ask me questions that I haven't yet asked myself. When I discover a film like that, I want to share it with the audience.

Petr: Documentary filmmakers can discover places and people that feature filmmakers could never even think of. The sources are authentic and believable, not just inspired or made up. That's what keeps me amused and surprised. With fictional film, it's very often predictable, derivative.

Can you give an example?

Petr: If you look at the film Body-Soul-Patient by director Jindřich Andrš, which shows how medical students learn to communicate difficult diagnoses to patients, the incredulity of some medical TV shows becomes even more apparent.

How are these new perspectives and unexpectedness mirrored in contemporary international documentary film?

Marek: Very differently. Let's take the main competition section of Opus Bonum. Switzerland’s Normal Love, following a pair of possible future partners, works with reality TV elements. Croatia's The Ship, about the defunct shipyards in Pula, straddles the line between oral history and found-footage. And the Qatari film Places of the Soul is an intimate and compelling reflection on family and closeness. Filmmaking is like a manuscript, and we’re always interested in its uniqueness.

Petr: Many people view documentaries only through the topics they cover. Of course, these are an essential part of them. But for us it’s still important how the filmmakers deal with the reality they capture and what artistic means they choose to make their statement as original as possible. It’s impossible to separate one from the other. Alongside the worlds that documentary filmmakers show us is the world of the artwork that we’re trying to care for.

Andrea: The diversity and originality that Marek and Petr are talking about is also realized through different media. The core of the program is and always will be on the cinema screen and in the discussions after the screenings. But, in addition to the films, you can also watch documentaries in virtual reality, read a documentary book, or play a documentary game. In Beecarbonize, for example, you develop strategies for relating to the world, with climate change as your adversary. Or in the VR zone, you can walk through a spatial documentation of women's prisons, where mothers can live with their children, and hear their stories and experiences.

Documentary film borders with cinema on one hand and with television journalism, news and the endless universe of internet videos on the other. Where is the imaginary line that determines what films you choose for Ji.hlava?

Andrea: The evolution is important. The emergence of a documentary film is preceded by research into the subject and conceptual consideration of the directorial and narrative methods and the means of expression. It's a deep dive into the subject matter, critical thinking, looking at it from different perspectives. For example, the making of The Mighty Afrin: In the Time of Floods was preceded by several years of learning about the environment and observing the lives of the inhabitants in a place that is affected by drastic floods for most of the year.

Petr: Time also plays an important role. The length of the film also allows us to understand what gives rise to specific facts. Consider the fate of the environmental activist in Lonely Oaks, who was part of a group of people defending the forest by living in the treetops. Everything, including the fights with the police, was filmed with a camera that the protagonist wore on his helmet. When he falls and tragically dies, his friends and fellow fighters are there commenting on this footage in the film. Activism, which is often reduced to a few images from television or social media, is seen at once in all layers: personal, ideological and purely procedural, including the doubts that have risen over this victim.

Marek: What separates artistic creation from mass production is the awareness of context and the ability to grasp it in an original way. When we observe events in the here and now, very often we lack the awareness of context. As Karel Vachek said, “When something is happening somewhere, like a demonstration in the square, I never film right below the stage, but always on the edge of the crowd.” In any case, the internet and the living magma of social networks is a space where interesting authors can appear. Just as the world discovered Billie Eilish recording her songs in her childhood bedroom with her brother, I expect something similar might happen with nonfiction videos.

This year's retrospectives go back to the beginnings of cinema and follow the iconic 1960s, the chronicle of modern Czech history and the creation of artificial intelligence. Why are they given such a large space at Ji.hlava?

Marek: The Translucent Beings section is an exceptional opportunity to see important works in a focused way and on cinema screens. In our home environment, we have the opportunity to see more films than ever before, but the cinema experience is incomparable. The festival adds intensity, energy and even the occasional chance to associate with other films being shown. In this way, we can discover unexpected connections and realise that film history is much more interconnected and interwoven than it may seem at first glance.

At the same time, we give space to personalities who have been overlooked and underappreciated in the past, which is especially true for women today. It's interesting to see how Marguerite Duras, Shirley Clarke and Susan Sontag, for example, have blazed a trail for today's generation of female filmmakers with their bold and original films. What is fascinating about Marguerite Duras's films even today is their directness, poetry and persistence. For example, in The Truck, she sits together at a table with Gérard Depardieu, reading texts and talking about cigarettes.

Petr: Retrospectives allow us to make often forgotten films visible, and in a way contribute to the knowledge of film history, or rewrite or expand it. All films are part of the same river; they refer to each other, it's a living organism – and it's only because these films are still screened that the audience can see them together, talk about them and put them in new contexts. It’s enough if just one viewer writes a post on ČSFD or letterbox. When we focus on the small genre of Czechoslovak film essays, which were shown in cinemas as pre-films before feature films, we see the image and spirit of the 1960s. The world-famous period of the Czechoslovak New Wave suddenly finds itself in a new context.

Andrea: Without knowing the context and history, our relation to the present is flat and short-sighted. For nine years, we’ve been presenting retrospectives of experimental films in which theme was key. It allowed us to look at and write a different history of film experimentation. We’re preparing a book based on this corpus of works. This year, we show how artificial intelligence intervenes in various ways in the creation of films representing reality. We’ve already shown such films individually, but if you want to understand a phenomenon comprehensively, the concentrated space of the retrospective is what allows you to do so.