Festival as a collectively created cultural artifact

In what ways does the Ji.hlava International Documentary Film Festival function as a collective? In which documentary films can we look for hope? And how do films help us understand the world around us? Read an interview with Andrea Slováková, Marek Hovorka, and Petr Kubica, the festival’s program council.

What does Ji.hlava mean to you as a collective?

M: For me, Ji.hlava has been an open platform from the very beginning. I enjoy the fact that the festival team is full of distinctive and experienced personalities, and it is important to me that we are able to function with open dialogue and respect. Our organizational structure therefore resembles an organism that is aware of the interconnectedness of its parts.

I believe that this form leads to greater involvement and motivation. Personally, I really enjoy continuously discovering the talents of my colleagues, and developing them, giving them space. I think Ji.hlava is an exceptional project in many ways, and its “collective character” is one of the reasons for this.

P: For me, the collective is expanding in concentric circles. It can be like ripples on the surface of water after we throw a stone into it – like when we screen a film that resonates. It can be like tree rings that express the festival’s interest and care for documentary filmmaking over several decades. It can be an image of many circles, each representing an area in which we participate, whether it be student life, professional organizations, or television.

It also means that there is a point somewhere, and the whole world is around it. The collective therefore grows into a community of people, united by documentary film.

A: The festival is a typical example of a collectively created cultural artifact. I appreciate the thoughtfulness of all the co-creators of Ji.hlava: the festival is also how it presents itself – how it speaks to visitors, how it communicates visually, how environmentally conscious it is.

A: The festival is a typical example of a collectively created cultural artifact. I appreciate the thoughtfulness of all the co-creators of Ji.hlava: the festival is also how it presents itself – how it speaks to visitors, how it communicates visually, how environmentally conscious it is.

Each film and its authorship is given sensitive care by our programming department, guest services, industry department, communications, and production – everyone understands that a film is a whole, including its presentation and the discussion after the screening; the film as a work is born in the minds of the audience, through the network of all this care.

What characterizes the work of the film collectives featured in this year’s retrospective, and why did you decide to focus on them?

A: Films are typically created by a collective of people who specialize in individual professions – directors, cinematographers, sound engineers, editors, dramaturgs, producers, and production managers. In the tradition of auteur cinema, they bear the signature of the director’s personality. Ji.hlava also focuses primarily on auteur documentaries – films that address important topics in a unique, auteur style.

Film collectives create works that reflect not the vision of a single author, but their shared vision; collectives usually function non-hierarchically, and their members rotate between individual professions. Nevertheless, their films are often formally inventive, distinctive, and socially impactful. What I enjoy about this retrospective is precisely this different, non-individualistic approach to authoring and “authorship.”

“What I enjoy about this retrospective is precisely this different, non-individualistic approach to authoring and “authorship.””

Speaking of retrospectives, you devote a lot of space across various sections to “food, dining, cooking.” Why is that?

M: Most of our retrospectives focus on filmmakers or countries. From time to time, however, we also focus on a theme seen through various films. It’s refreshing, and the result is often full of surprises. We decided on food when we were thinking about themes that unite us as a society. We believe it is important today to create a space that can bring people together, or even bring them back to each other.

From the beginning, Ji.hlava has wanted to be a place of connection, not only within the team, but also between different parts of society. What makes it unique in international comparison is that it takes place outside the capital.

P: In his book Mythologies, Roland Barthes has short essays entitled “Wine and Milk” and “Steak and Fries,” in which food represents a cultural symbol, and national dishes function as national myths. This exploration of identity in everyday life was the starting point for our research in the film and television archives.

My colleagues and I watched dozens of short films, television programmes, commercials, and spots. We were interested in what they preserve and what they reflect – whether it was the captured image of specific years, contemporary patterns of behaviour, or the rhetoric with which the socialist state spoke to its citizens.

My colleagues and I watched dozens of short films, television programmes, commercials, and spots. We were interested in what they preserve and what they reflect – whether it was the captured image of specific years, contemporary patterns of behaviour, or the rhetoric with which the socialist state spoke to its citizens.

We had a great partner in historian Martin Franc, who studies how food and the ways it is produced and consumed reflect cultural, political, and social changes, what diet says about society, and what values are expressed through it. Martin will be the guide for the entire retrospective, in which viewers will see a film about draconian punishments for black market trading at the beginning of totalitarianism, laugh at programmes about etiquette from the 1960s, and meet popular Czech artists who raved about baby formula products in the mid-1980s.

Returning to my initial reference to Barthes’ perspective: no fundamental analytical documentary on food has yet been created in the Czech environment, but its future creators can look forward to an immeasurable wealth of contemporary images.

A: This Czechoslovak perspective is complemented by global experiments. We begin with the first depiction of food in film – in Lumière’s Repas de bébé, from 1895. Historically, food has been both an object of depiction and audiovisual exploration, as well as a means of creating images – we will also see material experimentation, where various foods and delicacies chemically affected film material, or an attempt to produce vegan film raw material.

“Documentary filmmaking is the most progressive direction in cinema.”

What’s new in the program sections this year?

M: In recent years, we have put a lot of effort into communicating with many European and non-European film schools. Ji.hlava is a place that discovers talented emerging filmmakers, and we are deepening this identity in both the film and industry programmes. That is why, starting this year, all films in the First Lights section are film debuts.

Many filmmakers do not make a second feature film after their first one; according to some statistics, this is as many as 70 percent. That is why it is important to nurture these emerging filmmakers; it is one of the key responsibilities of film festivals. There will also be a special screening of films created during a film workshop of the renowned Cuban film school, led by Gianfranco Rosi and Jean Perret.

P: This year, we have significantly expanded the Constellation section, which focuses on films from world festivals. As a child, I liked the phrase “finger on the map,” and today I travel with my eyes from Lisbon via Toronto, to Busan in South Korea. Around thirty feature films, presented and awarded on the international scene, will showcase the breadth of themes and diversity of authorial approaches. And we can say with certainty that documentary filmmaking is the most progressive direction in cinema.

Can you mention one non-competition film that stuck with you this year? And what kind of imaginary viewer is such a film for?

Can you mention one non-competition film that stuck with you this year? And what kind of imaginary viewer is such a film for?

P: The film My Dear Théo, by Ukrainian documentary filmmaker Alisa Kovalenko, who joined the volunteer army after the Russian invasion. A soldier, filmmaker, and mother, she addresses letters to her young son, which are intimate confessions from the front lines. It is a video diary, a film essay, and a kind of testament. The viewer, numb and tired from almost four years of conflict, will once again realize the meaning of this struggle – not in the heroization of the fight for the nation or the state, but in the fact that in war, people sacrifice themselves for what protects humanity itself. I am glad that we were able to support the film as part of the Ji.hlava / JB Films challenge and that the audience will have the opportunity to meet the director at the screenings.

M: The film Writing Life – Annie Ernaux through the eyes of high school students by French director Claire Simon, who is returning to Ji.hlava after a few years, much to our delight, is a fascinating documentary study of the power of literature, the form of the education system, and a generation of French teenagers. The film is a pure observation of their conversations about the texts of this important writer, recently awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. But it is not a respectful recitation of learned phrases.

The film captures a lively dialogue about how the selected texts speak to me, how I read them, what they say about my own experience. What’s more, the students’ conversations were filmed across France, not just in selected elite schools, turning the film into a generational statement. France is renowned both for its education system, and for films about it. And this title, which premiered a month ago at the Venice Film Festival, surprises with its directness and original thinking about the present.

“Documentaries train these skills in us. Understanding the world, being able to analyse events and relate to them critically.”

Can we currently find perspectives for society to develop for the better? Where can audiences in Jihlava draw inspiration from this year?

A: I think that these perspectives and hopes are also linked to resilience, which is developed and strengthened by analytical and critical thinking. Documentaries train these skills in us. Understanding the world, being able to analyse events and relate to them critically. Where can we find inspiration? In beauty and poetry. In beauty and poetry.

The programme includes so many films that captivate with their aesthetic form – both visual and auditory. From Fascinace, for example, there is Solstice, created using cyanotype, the performative essay, Scattered Sea, and the animation of the northern lights accompanied by Sami songs in Vuoiŋŋat (the Sami word for ancestral spirits).

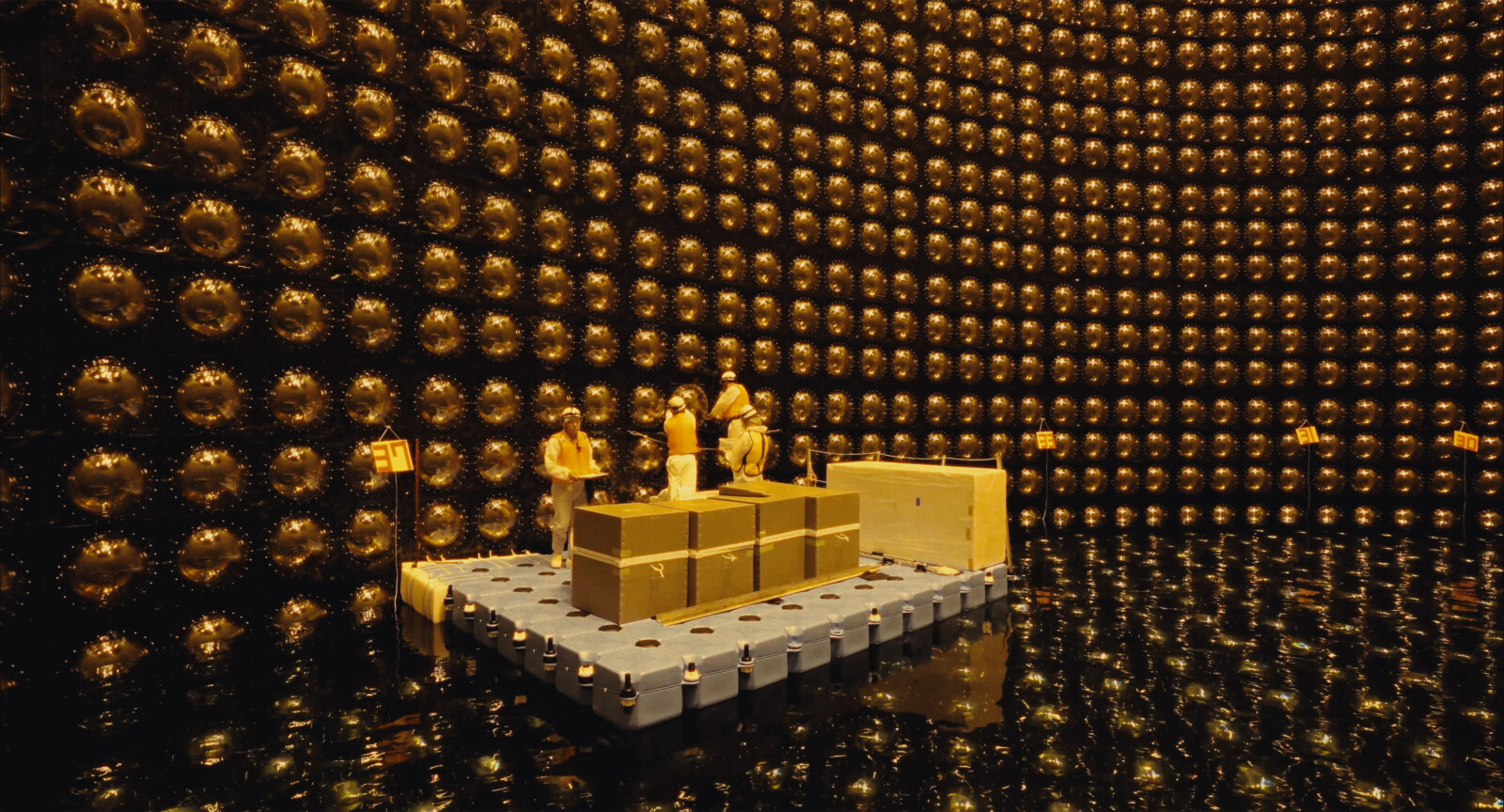

The extensive diary film by one of the greatest contemporary film poets, Peter Mettler, While the Green Grass Grows: A Diary in Seven Parts, is in the Opus Bonum competition, and Ben Rivers’ new film, Mare’s Nest, is being screened as part of the Constellation section. And also, from the power of nature and the reliability of science. For example, in the philosophical essay on science, Messengers (in the Testimony section).

The hare, the dove, or the figures? Which motif from this year’s visual appeals to you the most, and why? The poster is crossed by a diagonal line. Where do you think it is heading?

The hare, the dove, or the figures? Which motif from this year’s visual appeals to you the most, and why? The poster is crossed by a diagonal line. Where do you think it is heading?

P: The figures climbing upward with difficulty. Camus’ Myth of Sisyphus: The very effort of striving toward the summit is enough to fill the human heart.

A: The diagonal line is straight, precise, solid, with a clear direction. I associate these qualities with rationality, reliance on trustworthy sources, verifiable facts, and arguments. From this foundation, it is then possible to let the mind soar in breadth and height. The next milestone may be out of sight, but it is certainly a lot of thoughts higher and further.

M: A hare. Take a look at it when you encounter it at night in the streets of Ji.hlava. It embodies lightness, surprise, cleverness, and energy.