De – rrida – construction

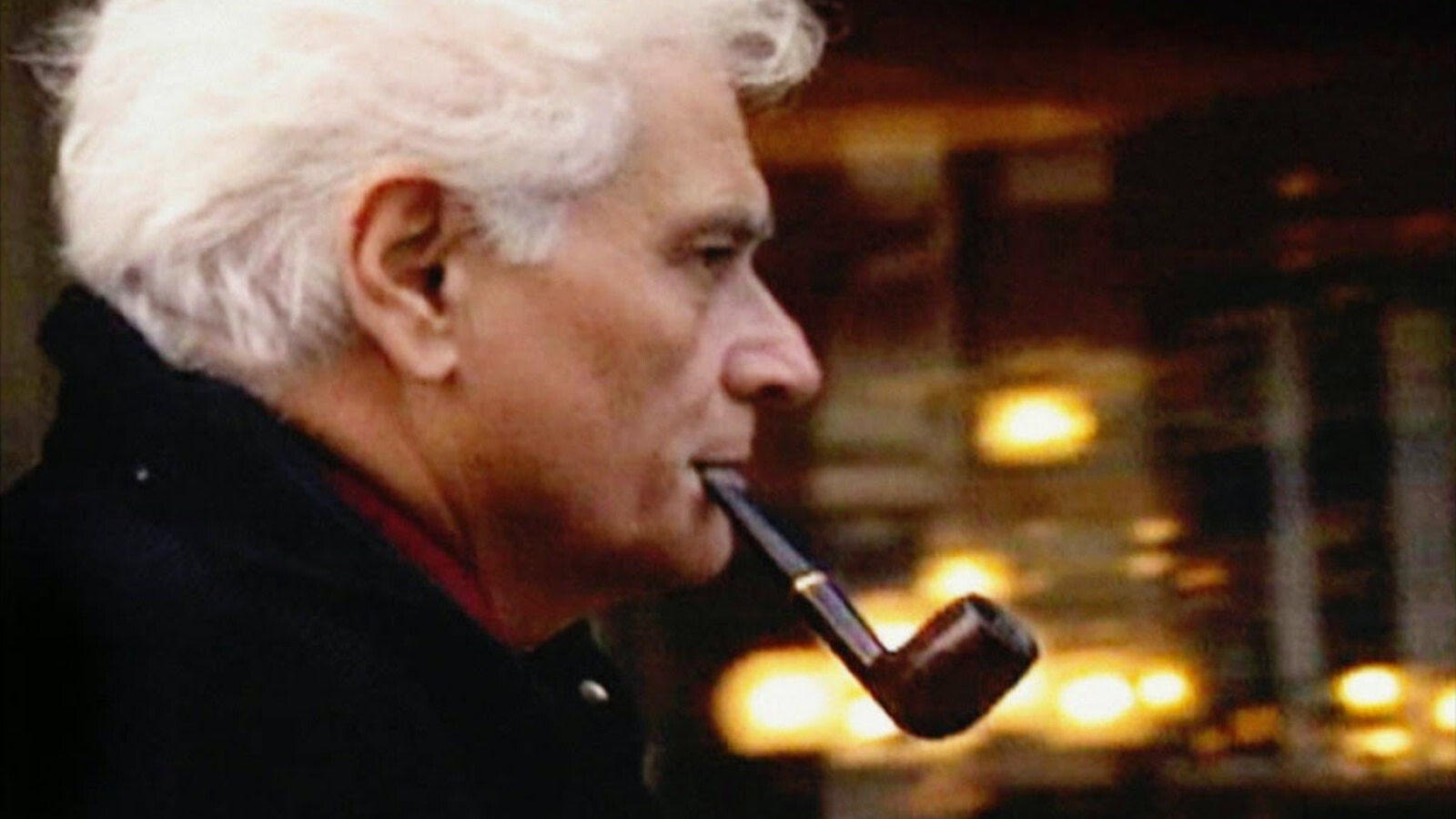

This year’s Visions du Réel documentary film festival in Nyon, Switzerland, featured the 2002 film Derrida as a part of the oeuvre of Kirsten Johnson, who worked as cinematographer on the documentary. The film follows French philosopher Jacques Derrida. But is it possible to film philosophy?

Where do the true meanings of words and concepts lie? How can such ideas be captured on screen? The film Derrida portrays French philosopher Jacques Derrida through footage of his lectures, public speeches, and also personal conversations at home. However, the main focus here is not Derrida’s life but rather the ideas that shaped it – specifically those on which he built his own philosophy.

It’s as if Derrida were the author of the film and not its subject. He says openly in front of the camera that he will not be speaking about his own life, and the camera almost never catches him at a moment that he wouldn’t plan himself. During the filming, he offers advice regarding what to cut and what to go back to, and we get the feeling that he is playing a game with the filmmakers, seeing who’s in charge, testing their patience, and carefully considering every word before he utters it. Derrida tries to give the film a form based on his idea of himself through his own ontology. And the filmmakers let him do it.

We feel doubt behind Derrida’s every word. He constructs his sentences in a way that makes the listener think about their meaning, to look for what is behind them. The fundamental idea of Derrida’s philosophy – namely deconstruction – is interwoven throughout the entire film. Although, like most philosophical ideas, it is considered primarily a theoretical directive of understanding, Derrida applies it in a very practical way in the film. Deconstruction dismantles the traditional meanings of concepts and tries to find their true meaning “beneath the surface”. He notes how, throughout the history of society, certain stereotypical concepts have been favoured and given greater distinction – the spoken word over the written, reason over emotion, masculinity over femininity. However, according to deconstruction, the traditional notion of monotonous opposites obscures the mutual inner conflict that forms the true essence of their understanding. Opposite sides have their pros and cons, both need each other, and both are defined by their antitheses. In the same way that Derrida deals with this eternal struggle with distinction and inequality in his books, he works with it in his biographical film in collaboration with the understanding filmmakers. In addition to non-specific speeches that attempt to puzzle out the meaning of the posed questions and answers, we often see footage of the filming of previous takes. Thus we are symbolically presented with reflections on the things that are hidden behind what we consider natural – things which reveal the true meaning. In this way, the film sometimes reaches an ironic level, for example, in a shot where Derrida is watching a TV displaying footage of himself watching a TV which is again displaying footage of himself.

What all lies hidden behind stereotypical meanings, and how far is deconstruction able to penetrate? Jacques Derrida, as a person from a Jewish family of Algerian descent that was affected by inequality like few others, was defined by these questions throughout his entire life. Just as he shaped them, he was shaped by them. And even though due to these questions he was often poorly received in both his professional and private life, he always believed that achieving equality and seeking the truth that lay deeply hidden somewhere was worth the cost.