A culture that is not individualistic

As part of the Ji.hlava retrospective Collective Film, the festival will also present the work of the Bolivian group Ukamau, one of the most powerful film movements in the country. “We did not see film as a space for personal self-realization, but as a means to build the nation,” says Jorge Sanjinés, one of the founders of the collective.

The Ukamau Group arose in the 1960s. What were the principles of its creation?

Well, before anything else, the interest to participate in the process of transformation of Bolivian society, that still was taking place as a result of the revolution in the year 1952. At that time, it had transformed the structures of a semi-feudal country into a bourgeois democratic country. This transit was generating new political and sociological expectations.

The young people of that time were still very impressed by the processes of the revolution of 1952, positively impressed, although we were also critical with regard to what that process had failed to achieve, what it had betrayed.

But we thought we were opening up revolutionary possibilities, particularly because the Cuban Revolution had triumphed. It was the Cuban Revolution which we felt soulful for: a country so close to the enemy, to the empire, that was liberated. Then it seemed to us that the liberation of our country was just around the corner, that it was a matter of organizing and fighting. At that time, we thought and believed in the armed struggle, as all the revolutionary world, because it was the only alternative in view, and also an alternative that had triumphed.

Therefore, we believe our work of filmmakers was a work of political militancy: we did not see the cinema as the place for our personal realization, but as a place to make the country, to contribute with our work to create greater awareness in the dominated society, with the cinema as an instrument of struggle.

In that period, the cinematographic movement New Latin American Cinema was also created. How was the participation of the Ukamau Group?

Well, the first surprise we had was when our movie Revolution, a small documentary, a short experimental film, was presented at the VI Viña del Mar Festival, in the year 1967. We didn’t go, but the film did and had a good impact. There, the jury included the famous documentary filmmaker Joris Ivens, who loved the movie and took it for submission in the Leipzig Festival, where it won the grand prize. And then, we were told that in this festival there were several filmmakers who were making political films; not many, but some.

Then, immediately, the following year, came to Bolivia Carlos Rebolledo, to invite us to attend the Latin American Cinema meeting organized by the Department of Cinema at the University of Mérida, Venezuela. And there we understood that we were living an extremely important process, because we discovered that several Cuban, Brazilian, Peruvian, Colombian, Venezuelan… filmmakers were working on a cinema committed to popular cause.

Like the Brazilians, with Glauber Rocha looking for a cinema with a Brazilian identity, or like the ‘Third Cinema’ with Getino and Solanas; it was a big ideological party from the joy of finding other Latin American filmmakers displaying the same concern, with the same political project against imperialism. In Mérida, I improvised a small speech, like other filmmakers; I didn’t know what I was going to say, but our films Revolution and Ukamau created a very interesting climate and I was asked to speak .

“It was a good blow in the snout of the empire“

That film had a great political impact.

Huge, huge. Until then, I was also in agreement that a movie does not make history, but that film, yes, changed history, because of what it led to… First there was a shock, because nobody could believe that the good and friendly and noble gringuitos, all the peace corps sent by Kennedy, the nice one, could do what they were doing. No one could believe they were sterilizing peasant women in a country with low population, with a high rate of infant and maternal mortality.

What was that? Then it was easy to accept that it seemed a diabolical lie, a slander, and it triggered a controversy in Bolivian society and several articles were published, some in favor and some against. The Congress of the country and the University appointed commissions to investigate the facts.

After a few months, almost at the same time, the two commissions assured that what the film was denouncing was true and that they had several tests, testimonies and documents. That helped the Bolivian government of General Torres to expel the peace corps from Bolivia, as did Evo with the DEA . It was a good blow in the snout of the empire (laughter).

… as a result of a political film. In addition, your movies had an educational role in the exhibitions and in the debates. In the manifest Toward a Third Cinema (Hacia un tercer cine, 1969), Getino and Solanas say that the revolutionary cinema has the role of discussing politics together with the people and think on action. How was the process of producing and exhibiting the Ukamau films here in Bolivia?

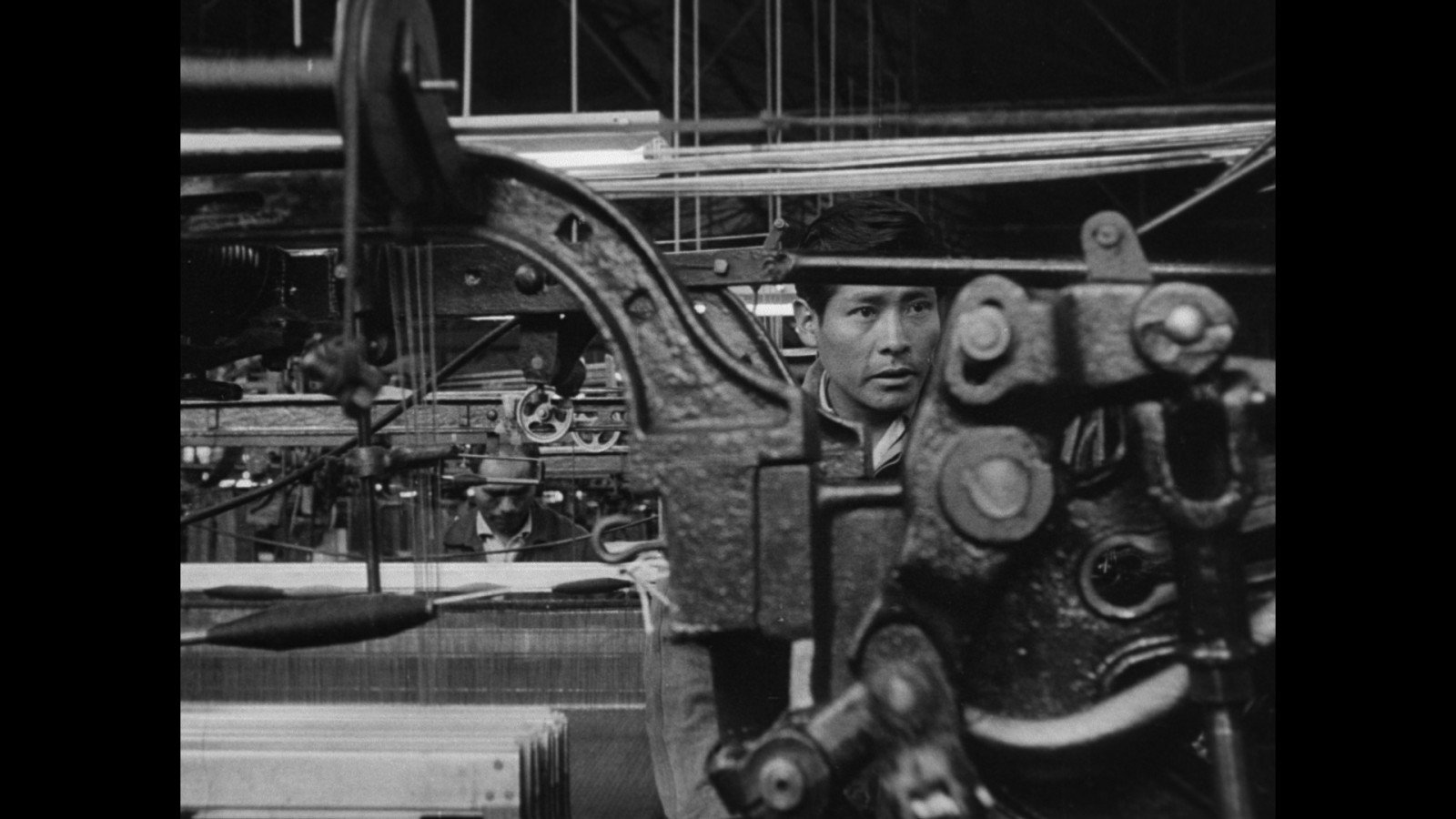

Exactly. We realized that it was not enough to make the films, because the films could be very revolutionary but if they served to win prizes at festivals or to impress the people of the cities, they were contradicting their objective. Therefore, we set up a system of dissemination: while preparing another movie, all of us that were part of the Ukamau Group would advertise the films in the factories, in schools, in the countryside, in mines…

For 18 years, we have done this work to bring our cinema to remote places of the country. It has been a process of great enrichment because we have learned a lot, as we learned with Yawar Mallku when we made the film and we understood for the first time that the indigenous people had a culture that was not individualistic, that they were organized around the idea of democratic power, which goes from the bottom up; we lived it in the flesh.

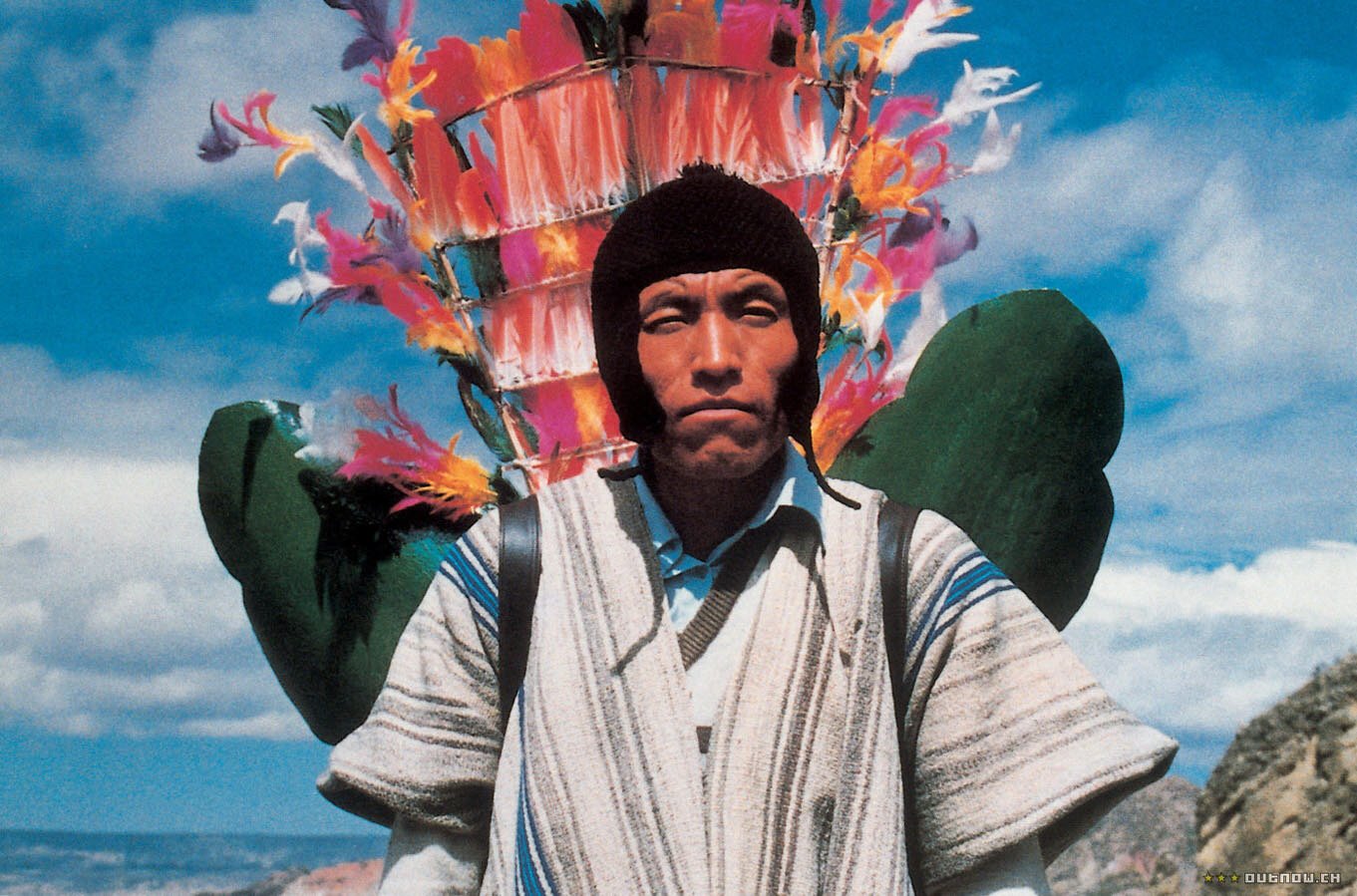

We realized that the individual protagonist did not make sense in the Quechua or Aymara indigenous community and that we had to achieve a collective protagonist, that is what we have in The Courage of the People. We have a single protagonist in The Clandestine Nation, but it is premeditated, because that individual actor lives and dies to be integrated into the collective: the true protagonist of the film is the collective, and Sebastián tries to redeem himself in order to be part of it.

How was the reception of the films in the communities?

One of the first films, Yawar Mallku, which was made to alert the indigenous of that act of criminal sterilization, didn’t work very well; not because they didn’t understand it (it was understood despite the fact that it is not linear and has flashbacks); what they all surely missed was the presence of the collective, because the film was focused on the individual. On the other hand, when we did The Courage of the People, the reception changed, the perception of the exhibitions was much more intense, and even more in Clandestine Nation.

When we showed Clandestine Nation in the Cinemateca, Beatriz interviewed people and many asked her: ‘And why does Sebastián appear again, wasn’t he already dead?’ They did not understand that game, don’t you think? That question was never asked in the popular bar in Lima, because the Aymara people who saw that reappearance thought it was very natural; this shows that we were matching the cultural codes of the Aymaras.

“First, it was necessary to fight the economic issue because, in the past, when we started, it was much more expensive to make movies than it is today.”

Your films are political already in the production process. So, how was the team work and the relationship with the communities?

First, it was necessary to fight the economic issue because, in the past, when we started, it was much more expensive to make movies than it is today. Ukamau was filmed in 35mm, we used a 35mm silent camera that was very large, very heavy, we needed 14 large battery packs to power it, the sound equipment used a perforated magnetic tape, everything was very expensive. We were able to do so because the state stepped in, but when we worked in Yawar Mallku we had serious economic problems, because we no longer had the support of the State, we were ‘us’ and nobody else.

We had a tiny budget of $300 to film, which is like $1000 now, more or less, a camera with a single 35mm lens, and it was noisy, and we had no recorder… and used a rubber check (laughter). A rubber check, and there was a very strong argument among the team about that.

Some companions, Soria for example, were very frightened because we were going to end up in jail. Then an idea occurred to me and I said: ‘Well, we can leave the prison, with security we are going to be able to leave it at some point, but we will never leave behind the frustration of not making the film. So, we do it!’ And so we did, and later faced enormous problems

I remember that when shooting ended in the Cata’s community we still didn’t have the money to pay the staff; the producer, who was Ricardo, had made several trips to La Paz and had not been able to raise funds.

I remember that when shooting ended in the Cata’s community we still didn’t have the money to pay the staff; the producer, who was Ricardo, had made several trips to La Paz and had not been able to raise funds.

On 30 December, with all friends wanting to return to celebrate New Year’s Eve with their families, I told them: ‘No, I will not go, I cannot leave because we are going to leave like always, we are going to repeat what they do, what whites and mestizos in society do, we use the indigenous people and then we disappear, no! Then I’m going to stay as a hostage, I cannot move from this community until you return from La Paz with the money to pay the people’. And one of the companions, an assistant, told me: ‘I am not going to leave Jorge alone, I’m going to stay’.

We stayed, and almost died. Almost died because on the 31st they held a tremendous party in the community, where everybody drank burning alcohol (laughter); they were unaffected by it, but it burned our tongues, it pulled out pieces of skin off our tongues.

And we were so intoxicated that we slept on the floor, we had no strength even to walk to the cot, we could have died; the fact that we were very young saved us. Nor could we say no to the people, it was not that we like to drink a lot, but that came and… ‘companion, brother, brother’… with me, everyone wanted to toast with me, I had to drink with them all, with the collective. At that moment, the collective cost us dearly (laughter)

Some cinema groups, like the Argentinian Grupo Cine de la Base, which Raymundo Gleyzer was part of, had a very strong relationship with revolutionary organizations… Was your cinema also in contact with organizations here?

Some cinema groups, like the Argentinian Grupo Cine de la Base, which Raymundo Gleyzer was part of, had a very strong relationship with revolutionary organizations… Was your cinema also in contact with organizations here?

No, for a very simple reason: the Bolivian left was, I believe that it still is, a very small left, a left made of rulers, that has not been cured of this ruler behavior in their relationship with the indigenous. That’s why they despised the work we developed with the indigenous.

I recall a discussion with a great intellectual, that I am not going to name to preserve his image, a great man, a very intelligent man, who said to me: ‘No, you’re wrong, you all are wrong: it’s wrong to exalt the culture of the indigenous people, we have to take the indigenous as proletarians, we must make them revolutionaries. Leave their traditions, they are things from the past, which harm them. They are petit bourgeois and land owners and we have to incorporate them and turn them into revolutionaries’.

A great leader of the Bolivian left. How could we have relationship with people who thought like that? And that’s why they have failed, they have never understood their own country, because they are racists, deep down they are racists.

“I still don’t know how we were able to do it”

How was the production process? Did your movies have direct relationship with the indigenous movement?

More than with the movement, with the communities directly, with the Miner Unions, for example. The Courage of the People was done this way, it could not have been done differently, and therefore they participated in the film in a creative way. How could we tell Domitila Chungara ‘you have to say this’? How? It was impossible! We had to listen what she had said, respect what she had to say and say: ‘Well, we are going to do it again’. Nothing more.

And the involvement of the Miner Unions was decisive: without their support, the militant support, we would not have made the film. They protected us in many ways, because it was very dangerous to work there. At that time, the Siglo XX Mine was controlled by the Ranger, which was ruled by Siles, who had just murdered Che and all that.

If such people had discovered us carrying arms and military clothing in the middle of the night, we would have been killed directly. We did it just because we had the protection of the population; they would warn us, come running and say: ‘The army is coming’. Then, we would all hide the arms and get into the houses, let the patrols pass. This way, The Courage of the People was made, and it was made very fast: from the moment I went to write the script during two weeks in Yungas, until the film premiered in the Pesaro Film Festival, 4 months passed. A film with two and a half hours of duration when it was all finished, with thousands of extras and with pyrotechnics, with effects, with reconstructions of the war.

I still don’t know how we were able to do it, because today, if I thought to produce a film like that, I would say, at least, a year, we could not do it sooner.

And what was the impact of that film in that period?

And what was the impact of that film in that period?

In Bolivia, it premiered seven years later, in the year 78. It was very strong, I think… The military were still in power and the film stayed for a week in the theaters, but when it started hitting society, the film was cut and censored.

Before, two days after the premiere, as the film accused the commander of the army, General Arce, it was published in the newspaper a note saying that everything that slanderous movie said about the army was a lie, slanders from a terrorist group called Ukamau Group, and requiring the director of that group to issue a public retract.

The next day, in the same newspaper, we presented our answer to the army commander: ‘General Arce, we cannot retract the truth, and if you threaten us with a civil-military trial we are fully prepared to attend, because such a trial will give us the opportunity to disclose to the Bolivian society a series of documents and testimonies that we have not had time to put on film’ (laughter). And that’s how it all ended, the army commander kept quiet, and shortly after, the film returned to the theaters.

“The cinema as an instrument to preserve a memory, because there was no other way.”

Did you have other problems with repression by the dictatorship?

Yes, of course. Threats by phone, many times: that I was going to be killed, calling me a red bastard, that they were going to shut my mouth. After that, a place we had in Sopocachi was robbed, and they took films and documents. We were included in the list of people that had to be killed, we were in the third place alongside Luis Espinal. We had to hide when going along the city, as we were being pursued by the military, we had to leave the country illegally, we stayed seven years in exile… it cost us dearly.

What changed in your films since the group started?

The cinema of Ukamau Group’s first stage is a cinema of direct confrontation, because at that time, for example, there was no television. When the events that inspired The Courage of the People happened in the year 1967, the newspaper only published a small piece about the massacre of San Juan, where three people had been killed in a scuffle between the police and some drunken miners. And nobody complained, nobody rectified that, no organization, not even the Miners Federation, nobody, nobody rectified that.

It was then that we made the decision to make The Courage of the People, because that had been barbaric. It was a memory that was being lost and there had been a massacre of people there, it was politically motivated, because of imperialism… and nobody said anything. So we made this film, because I was playing that role then: the cinema as an instrument to preserve a memory, because there was no other way.

It was then that we made the decision to make The Courage of the People, because that had been barbaric. It was a memory that was being lost and there had been a massacre of people there, it was politically motivated, because of imperialism… and nobody said anything. So we made this film, because I was playing that role then: the cinema as an instrument to preserve a memory, because there was no other way.

Then came the democratic process, and since then we have left the cinema of direct confrontation and have made films of greater depth, as in the case of Clandestine Nation and other films that touch on issues of identity or racism.

Interview was originally published in Comparative Cinema (Vol. IV, No. 9, 2016)