The Growth of Documentary Ethics Debates in the Streaming Era

A fifth of Netflix’ and full third of Disney+ offerings are documentaries. The viewership of the documentary miniseries Tiger King even outpaced The Mandalorian. One-fifth of Netflix's offering and a whole third of Disney+'s content consists of documentaries. Are companies exploiting the reputation of documentaries while seeking ever-greater audiences? Is documentary production growing faster than its standards? An what does non-extractive or care-centered filmmaking look like?

Professor Patricia Aufderheide is one of the most prominent figures in the field of documentary film ethics. Her text was originally published in the anthology 'Ethics in Documentary Film I: Power and Power Relations.' You can download the entire anthology for free here (in the Czech language).

Introduction

Between 2014-2022, an unprecedented, field-wide conversation has emerged in the U.S. about ethics and accountability in documentary. Documentary filmmakers in the U.S. have never previously established any shared ethical expectations, although some have worked within the journalistic standards and practices of broadcast organizations such as NBC, CBS and PBS. Visual anthropologists and other academics have also established expectations (Gross et al., 1988, 2003; MacDougall & Taylor, 1998; Winston, 2000), without those expectations feeding back into commercial field practice. Finally, consultants and advisors have published ethical guides, which have also not been incorporated into industry norms (Mobina et al., 2016).

Documentary filmmaking historically has avoided ethical standards actively, even while its practitioners made grand claims about its power to persuade. British documentary founder John Grierson established a durable tradition by straddling the line strategically between art and information, in order to win government contracts for propaganda films (Aitken, 1990).

Filmmakers have always had economic incentives to duck on ethical standards, as well. But until recently there was rarely any public scrutiny of behavior. Until two decades ago, it was a relatively small field, and one that was unlikely even to provide a viable income. It is still typically executed by small, family-held companies and by individuals, who often made a living working on industrials and commercials (Chattoo, 2016). They are small actors working with big companies to make and distribute their work. Filmmakers have thus not had incentive to set standards that might make getting new work harder, or that might create high expectations that might cost more than funders are willing to pay.

Previous research (Aufderheide 2012) demonstrated a profound and agitated concern among filmmakers with the ethical challenges they face in daily practice, especially in the then-burgeoning field of cable documentary programming. Other research has demonstrated the sensitivity of participants to ethical issues in the way they were treated during filming (Sanders, 2012). However, even when directly approached, leading members of the independent documentary film community have resisted even sharing thoughts about ethics in public on film festival panels, much less undertaking a norms-resetting process.

Documentary Film Growing Faster than Its Standards

The absence of articulated ethical norms becomes ever more important, as documentary does. Documentary film has never been more important in the media diet of Americans (Aufderheide and Woods 2021). Documentary production has grown dramatically in the last three decades as production fueled by Discovery, National Geographic, Amazon, Netflix, Hulu and niche content providers shows us. Market data from Nash Information Services (2021) demonstrates documentary’s rapid growth at the box office in recent years. The number of annual documentary theatrical releases has more than tripled since 2000. Nonfiction programming on TV has experienced a similar upward trend. Likewise, nonfiction programming is an increasingly important content category on streaming platforms. A a fifth of Netflix’ and full third of Disney+ offerings are documentaries. Netflix’s Tiger King (2020) was one of the most watched SVOD original series of 2020, outpacing The Mandalorian (2020) on Disney+ (Nielsen, 2020). The documentary genre, up 120% from 2019 to 2020, was the fastest-growing genre on streaming in 2020 (Fischer, 2021). It continues to grow; a Parrot Analytics report estimated growth of streaming documentaries as up 77% between 2019-2022 (Galuppo & Kilkenny, 2022). Filmmakers themselves, even those in the heart of the commercial industry, express dismay over streamer demands to use prefabricated script guidelines and to focus on sensational subjects (Weideman 2023).

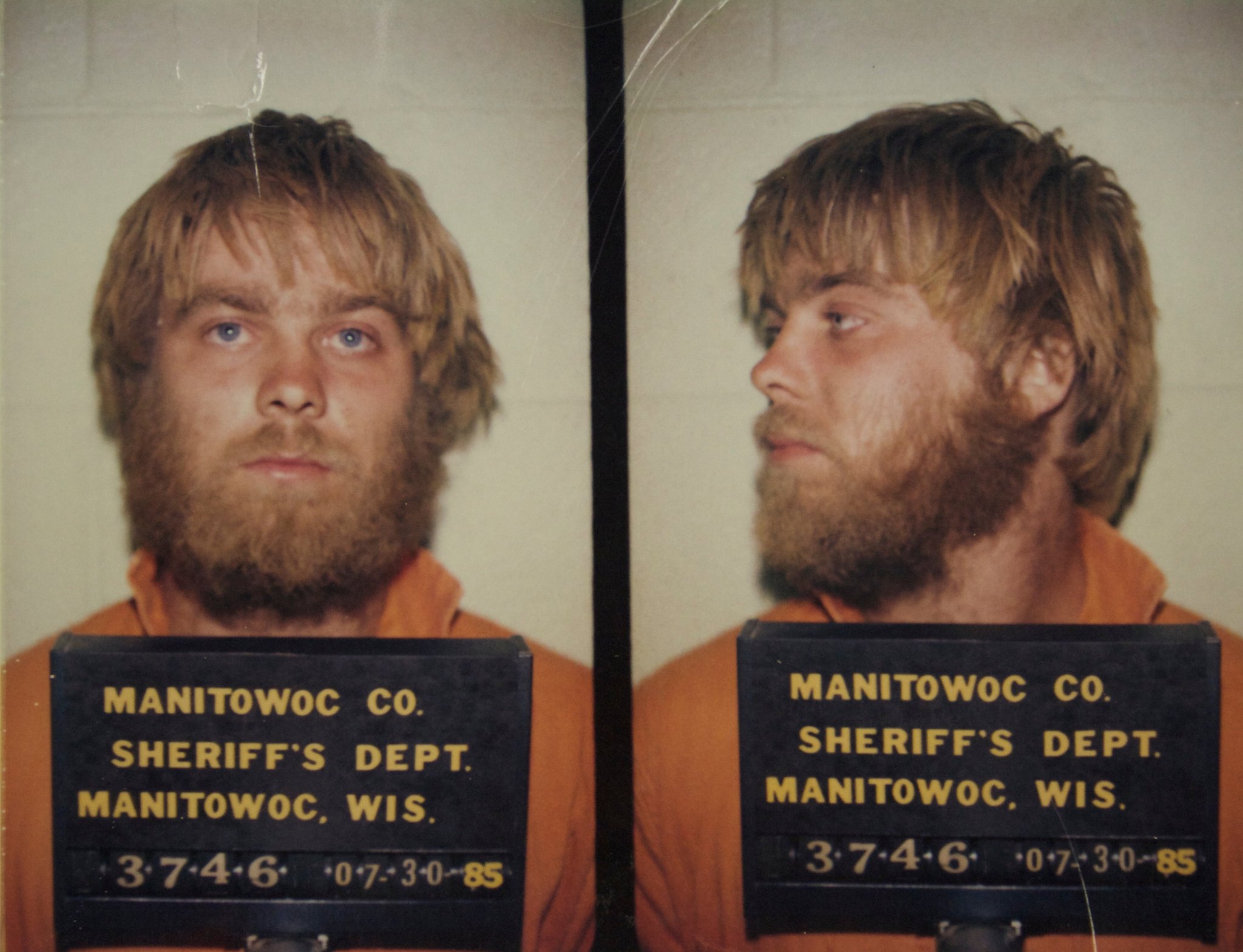

Brands exploit the reputation of documentary, while seeking ever-greater audiences. “Documentaries help form the architecture of the studios’ brand, signaling that they care about the climate justice, Me Too, and Black Lives Matter movements as well as projecting an image of the organization as transparent, authentic, and truthful,” noted a leading documentary scholar (Glick 2021). And so even programs that are not documentary are reclassified to attract the gloss. Operation Varsity Blues (2021), a fiction docudrama starring Matthew Modine, is classified on Netflix’s site as a documentary. Netflix’s Tiger King (2020) had many reality-TV aspects, but it was also marketed as a documentary. True-crime series can use the trappings of investigation, while selecting the evidence to oversimplify and crusade. For instance, the Netflix series Making a Murderer slighted evidence against its central characters, leading some to characterize it as “highbrow vigilante justice” (Schulz, 2016). But it became wildly popular, and it led to a national petition demanding exoneration.

With the exception of public TV, sponsorship has become a largely unguarded area full of conflict-of-interest possibilities. Maria Schwarzenegger’s child’s addiction problems with Adderall led her to provide her foundation’s funds for a Netflix documentary, Take Your Pills (2018); the foundation’s influence is unknown. Verizon fully funded a film by Rory Kennedy, Without a Net (2017), on issues affecting the FCC’s e-rate policy; the film does disclose Verizon’s full funding, but does not disclose Verizon’s interest in e-rate or conflicting views about how that fund is managed. The film’s storytelling effectively builds a pro-Verizon argument for how to allocate those funds. Bill and Melinda Gates’ foundation provides funding that results in substantial media production, where funder influence goes unexamined. Paying people for their interviews—even giving them their talking points—as seems to have happened in Tiger King (2020)—goes unscrutinized. Mike Rowe’s Six Degrees on Discovery+ is openly funded by fossil fuel corporate interests, reflected in his constant plugs for fossil fuel. ( (Aufderheide and Woods 2021); Ruwer, 2020; Schwab, 2019; Schwab 2020; Noor, 2021)

Public Knowledge and Documentary

American viewers place enormous trust in documentaries, at a time of plummeting confidence in mainstream media and as traditional journalistic outlets, especially local journalism, have declined (Abernathy, 2020). As a 2020 Pew Research Center study reveals, nearly half (44%) of Americans surveyed believe that news organizations publish deliberately misleading information and 38% say they aren’t confident in the factual accuracy of the news. More than half (55%) of those surveyed also expressed a desire for greater transparency with regard to whether the news stories they consume are based on fact or opinion (Gottfried, Walker & Mitchell, 2020). More than half (52%) of Americans express confidence in the veracity of scientific information in documentary films and nonfiction TV programs. That percentage drops to 28% when the source of information is a news outlet (Funk, Gottfried and Mitchell 2017). A 2021 American Press Institute study hints at why this skew might happen. It finds that people respond to framing that reflects moral values, including fairness, caring, loyalty, heroism and loyalty, and that common journalistic assumptions about the integrity and the public mission of journalism are not necessarily widely shared by the general public (American Press Institute, 2021).

This public trust in documentary has been exploited cynically—or, in some cases, delusionally. Misinformation on Covid-19 was spread widely, for instance, through the documentary Plandemic (2020). ShadowGate (2020) peddled a vast and utterly unsupported conspiracy theory about global cabals. Both were seen by millions on social media before being taken down. (Brown, 2020; Newton, 2020)

Documentary has also been weaponized by ideologues, particularly on the right; companies such as Citizens United and Dangerous Documentaries have entire slates. Steve Bannon has leveraged money from extreme-right funders, the Mercer family, to produce scurrilous documentaries such as Clinton Cash (2016) (Goldstein, 2017). Michael Pack’s Created Equal: Clarence Thomas in His Own Words (2020) was a fawning, in-his-own-words portrait of the controversial Supreme Court Justice. Pack’s self-asserted documentary expertise was used to credential him for his disastrous, if short, leadership of the U.S. Agency for Governmental Media (Gold, 2018).

Racial Reckoning

Simultaneously, a national conversation about equity and justice, spurred by the racial reckoning developed from 2014 (the police murder of Mike Brown in Ferguson) through 2022. That social movement birthed a range of organizations, including Black Lives Matter, and actions such as wildcat and unionized strikes. The same ferment reached the documentary community.

A new but long-brewing conversation blossomed in public, often at film festivals, where typically minoritized filmmakers openly raised questions about what they saw as “extractive” filmmaking—work in which privileged, often White filmmakers parachuted into communities and stories of minoritized people to tell stories about them to a typically-privileged audience.

Natalie Bullock Brown, a Black filmmaker and professor, and Sonya Childress, a Black expert in social-action engagement in documentary film and long a member of the Firelight Media group, which promotes and coproduces BIPOC films, jointly described the conversation that was bursting out as a social movement in resistance to a colonizing narrative tradition in documentary:

This new class has sounded the call for a reimagining of the nonfiction filmmaking ethos, built on values of accountability, consent and respect for the agency of documented communities; and of a trust-based relationship between director and protagonist. Bearing the weight of a form rooted in Eurocentric ideology, this new class aims to take back nonfiction and use it as a vehicle for both personal expression, and as a tool to strengthen movements, build solidarity across disenfranchised communities, affirm the experiences and history of people in their communities, heal from trauma, and inspire joy and political action. Not unlike the filmmakers of the Third Cinema, this new class has its eye on liberation — from patriarchy, classism, nationalism, racism and capitalist exploitation. (Brown & Childress, 2020)

Childress, in another article, also pointed out that the lack of formalized ethics code in the documentary field left deep bias entrenched and unchallenged:

What is lacking are protocols for ethics and accountability across the industry, from filmmaking to artist-service provision. That begins with a full-throated acknowledgement that racial, gender, and class bias are baked into both the artistic form and the industry. From that acknowledgement must come the development of new norms and protocols that represent the diversity of those in the field, and a shift in power and privilege from those who historically held it. Ultimately, new protocols must be built to ensure filmmakers and film institutions do not harm the communities and artists they aim to serve. (Childress, 2020)

At the same time, organized groups were coalescing within the documentary community, as they were in other sectors. Some of these organizations focus on labor rights; they pull together producers (Documentary Producers Association), editors (Alliance of Documentary Editors [ADE]), or makers as workers (labor unions including the Writers Guilds East and West). Others are organized around demographics of a group struggling for greater media presence, for instance FWD-DOC (disabled filmmakers), the Undocumented Filmmaker Collective (undocumented immigrant producers), A-Docs (Asian-American filmmakers), Brown Girls Doc Mafia (BIPOC women makers) and Beyond Inclusion (a group of producers focusing on pressuring public broadcasting to become more ethnically diverse). This mobilization, including during the pandemic, has had some effect on the field. For instance, there have been meetings between PBS and Beyond Inclusion, and individual filmmakers have adopted some of FWD-DOC’s suggestions. It also has changed the tenor of discussion, whether at events such as festivals and conferences or on sites such as D-Word—where ethics is an energetically engaged subsite—and listservs such as D-Word. Independent documentarians have become more self-aware of their collective capacity, and of their need to act collectively. Between 2020 and 2022, several field-wide conversations were had on treatment of participants in Sabaya (Arraf & Khaleel, 2021), Roadrunner (Rosner, 2021) and Jihad Rehab (Begum, 2022), for example. Film festivals began featuring public conversations about non-extractive or care-centered filmmaking.

New organizations have begun creating norms-setting documents and resources. For instance, ADE has created guidance on how much time to budget for editing, in response to an industry-wide speedup. Undocumented Filmmakers Collective has developed guidance on working with undocumented participants. FWD-DOC has designed a toolkit for working with disabled team members and participants (FWD-DOC, 2021).

Ethical Frameworks: Media Companies

Filmmaking standards efforts have responded both to the rapid changes in the industry as documentary burgeons, and to the moment of racial reckoning, leading to deeper conversations about equity and justice.

There are strong business motivations for journalistically-rooted media organizations such as PBS, NBC, The Atlantic and CNN to enter into documentary production, as the medium carries prestige, has growing popularity, and is within the general mandate of these mainstream news producers. As smaller players in the media industry, they aim for compelling storytelling that can potentially win awards. At the same time, these outlets’ reputation for integrity is key to their brand. In fact, year after year, PBS is rated the most trusted brand in America. That reputation allows such organizations, which cannot compete with mega-corporations such as Amazon or Netflix to claim a market niche.

These business pressures have forced executives to re-examine their interpretation of standards not developed for the medium, as they both face competitors and also strive to extend their own brands into a new environment. Among the changes has been PBS’s decision boldly to showcase its standards and practices, and to develop resources that make them the basis for tutorials for filmmakers, at pbs.org/standards. This is the first time that PBS has made such an in-depth resource openly available to all. Part of its goal, according to the head of its standards department, Talia Rosen (personal interview, October 17, 2021), was to ensure that filmmakers who want distribution with PBS develop processes that make it possible for PBS to accept them when finished. Part of the reason was also to encourage a younger generation of producers to see PBS as a mission-driven organization aligned with producer concerns, in an otherwise ruthlessly commercial environment. Another change has been NBC News Studio’s decision to develop filmmaker training workshops, in which they can cultivate new talent and also encourage production in accordance with NBC’s standards and practices. BIPOC Doc Editors has created a database to make it easier to look for a BIPOC editor.

Documentary Accountability Working Group and an Ethical Framework

Building on the racial reckoning conversation and its related conversations in the independent documentary community, an ad-hoc, seven-person group, the Documentary Accountability Working Group (DAWG), formed organically. The group is majority BIPOC, each with at least 20 years of experience in the field, and from several regions of the U.S., and I am proud and grateful to be a member of it. Its members are well networked into many of the other organizations that have sprung up in the last few years around equity issues. Like many other filmmakers who work on social-issue documentaries, often telling stories from underrepresented constituencies, this group was also alarmed by the implications for field practices from the industry speedup and new money flowing into the sector. Between 2020-2022, it created a norms-setting document, “From Reflection to Release: A framework for values, ethics and accountability in nonfiction filmmaking” (Aufderheide et al. 2022).

The research to develop the concepts in this Framework was extensive, over more than two years, and primarily involved direct consultation with members of the independent documentary filmmaking community. The selection was guided by two criteria: an emphasis on BIPOC, women, and minoritized filmmakers; and on film projects featuring BIPOC, women and minoritized people. The group conducted six closed-door convenings with filmmakers who make such films, engaging more than 100 documentary filmmakers. It also conducted two closed-door convenings with 40 people featured in documentary films. Finally, it conducted five sessions between PBS staff and 45 diverse filmmakers, sharing their understanding of current best practices in working with minoritized participants. Staff of film-support and funding organizations including Chicken & Egg, POV, and Black Public Media, program officers at the Ford Foundation, Perspective Fund and MacArthur Foundation, and professors at universities such as Spelman University, University of California Berkeley, American University, and University of Southern California helped the group assemble the participant lists.

The group held panel discussions and workshops to share results and solicit feedback at industry events, including Getting Real 2020, the Double Exposure Film Festival and Symposium 2021 and 2022, the Based on a True Story conference associated with the True/False Film Festival in 2022, Gotham Week and the Gotham Documentary Features Lab, the New Orleans Film Festival, BlackStar Film Festival 2021 and 2022, and the University Film and Video annual conference 2022, among others.

Learnings from Conversations

This research process revealed the logics behind filmmaker choices when faced with an ethical decision. Filmmakers working with minoritized people, chronicling their experience, routinely observe commonly prescribed standards in the breach, because of strong beliefs that honoring them would be unethical. Standards were often developed to ensure there is distance between the maker and the subjects or interviewees, such that the final product can be trusted not to be unduly influenced by those with a stake in the story. These filmmakers by contrast experience the requirement of distance between subject/interviewee and maker to be, in many circumstances, inhumane. For instance:

- Journalistic standards prescribe an objective and balanced approach. By contrast, independent filmmakers rarely undertake what could become a years-long project on editorial assignment, or from a dispassionate perspective. They openly acknowledge that they believe the stories they tell are important, and the point of view of people they profile to be underrepresented. They share an investment in that perspective with their participants.

- Journalistic standards and current broadcast standards flatly prohibit payment to subjects/interviewees. The filmmakers believe they have an obligation to not impose greater burdens on the people they work with than those people already experience, and so they want to defray their financial costs.

- They want to minimize security risks for those people, and so may take measures that alter the scene; for instance, in the case of Always in Season, a film about a recent lynching, filmmaker Jacqueline Olive filmed the mother of the victim in another town, in order to not put her at risk from more hostility from White neighbors.

- Journalistic standards flatly require not showing media in advance of release to participants, to avoid influence on the reporter’s decisions. These filmmakers want to explain the process, and often to show their participants the process, including interim edits. For instance, in Outta the Muck, Bhawin Suchak and his team routinely made small, edited packages of current work, simply to show participants the process of turning raw material into documentary.

- The filmmakers also typically want to show the completed work to the people whose stories they documented before the public does; they are concerned about accuracy, about respecting the viewpoint of those people, and about not upsetting or shocking them at the time of release.

- The filmmakers strongly believe that such measures, by maintaining trust with participants, make the film more accurate, more intimate, more revelatory. At the same time, in the absence of commonly articulated standards and practices other than journalistic ones, they fear sharing their own practices more widely. Doing so would potentially cut off avenues of distribution and also future work, and also incur reputational risk should others disagree. This was revealed among other ways by the difference in confidential conversations and public events. Filmmakers and participants were both strikingly more forthcoming in confidential conversations.

As well, because of the tactics they use to disguise their actions in support of their participants, they often do not provide either transparency to the audience on their relationships, nor do they offer credit to the participants for what may become an editorial and creative contribution to the film. Thus, taking one action to support participants may involve taking other actions that they themselves find to be unethical.

Also because of the lack of transparency about process, filmmakers are often unable to find funds appropriate to the need to support participants. For instance, the custom of festivals is to invite a participant, and potentially to pay transportation. But many minoritized participants cannot afford to participate without grievous harm to their monthly budget. Furthermore, as the group learned from participants, in some cases the participants who did attend and speak at festivals found it upsetting, forcing them to relive difficult or stigmatizing moments. They found their traumatic experience to be invisible, often even to the filmmakers. But there has been no custom to include a line item to support mental health, e.g. to include a therapist either in production or afterward.

Ethical Framework

These conversations then infused a process led by DAWG of refining an ethical framework for filmmaking about and with minoritized participants. That document creates six core values, stressing the need for a care-centered approach to the filmmaking team, the participants, and users/audience. It explores implementation in five phases of production: Reflection (why do this project); research and development; pre-production; production; and post-production. Rather than offer prescriptions, it provides typical questions that come up in these phases, and offers an example within each of how one filmmaker addressed them. This structure creates opportunities for an evolution of new norms, conducted in public and on the basis of a shared set of minimal expectations.

This effort in some ways echoes the concerns of an Institutional Review Board, to protect the participants in a study from harm. It goes beyond such concerns by extending the notion of care to both the filmmaking team itself and to the users/audiences.

The effort to consult the field and develop a standards document is the first step and a sine qua non to changing norms, but in itself does little. Next steps include garnering institutional endorsements, publicizing and discussing the shift in public, and consulting with institutions that currently have differing standards and practices documents. Current endorsers include the major independent documentary coproduction unit in U.S. public broadcasting, Independent Television Service (ITVS); the leading professional association for film production professors, University Film and Video Association (UFVA), the Alliance for Media Arts + Culture, and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. The Framework is scheduled to be showcased at film festivals throughout the next year.

DAWG has also partnered with the makers of the 2022 documentary film Subject, to host conversations about film ethics. Subject, by Jennifer Tiexiera and Camilla Hall, reveals the lifelong effects of being a film participant, focusing on six participants who describe their journey. Arthur Agee, a lead participant in Hoop Dreams, was a middle-schooler when he started working with Kartemquin Film’s team. He leveraged the attention the film brought him to build a career. On the other end of the spectrum, Margie Ratliff’s life became a torment when a film team focused on the murder of her mother, possibly at the hands of her stepfather. The Staircase became a popular true-crime series, and forced Ratliff into a never-ending news cycle that forced her to endlessly relive the worst moments of her life. Jesse Friedman was a lead participant in Capturing the Friedmans, a film about his father, arrested for pedophilia, and his own struggle to disprove the same charges against him. Originally enthusiastic about the film, which he believed was essential to ultimately freeing him from prison, he became disillusioned when he could never escape the association with the charges, because of the film’s popularity.

The film’s directors made the participants they worked with producers of the film, and involved them in the process throughout. They paid for participants to attend screening events and let participants choose how much they wanted to participate in them. Subject is thus one case study in a care-centered approach to documentary filmmaking, although the choices its filmmakers made are made in context of their circumstances and storytelling. In other words, they do not provide a template, but one instantiation of implementing values in practice.

Other organizations have also taken note of, and inspiration from, the work of DAWG. For instance, a maker of documentaries about and with imprisoned people in the U.S. created a set of standards grounded in the DAWG framework (Chan 2023).

Conclusion

Ethics conversations matter. They are shot through with questions of power and privilege, and how to mitigate them or leverage them in the service of a mission. U.S. documentary filmmakers have largely dodged these questions, or chafed under internal standards and practices that are poorly designed for their form, medium and subject matter.

At this moment, commercial forces, led by the economic effect of the streamers, and socio-political forces—the social movements demanding redress for systemic injustice and inequality—have created the conditions for a sober conversation about shared expectations for accountability in documentary storytelling. The norms documents and projects resulting are nascent, and untested. They are also grounded in actual industry practice and problems. They deserve scholarly attention.

---

| Patricia Aufderheide is a professor at the School of Communication, American University in Washington, D.C. and the founder of the Center for Media and Social Impact. In her research, she explores the ethical issues that American documentary filmmakers identify in their work. She is also the author of the popular publication Documentary Film: A Very Short Introduction. |

Bibliography:

Abernathy, P. M. (2020). News Deserts and Ghost Newspapers: Will Local News Survive? Chapel Hill, NC: Hussman School of Journalism and Media. Retrieved from https://www.usnewsdeserts.com/reports/news-deserts-and-ghost-newspapers-will-local-news-survive/

Aitken, I. (1990). Film and reform: John Grierson and the documentary film movement. Routledge.

American Press Institute, Media Insight Project. (2021, April 14). Do Americans share journalism’s core values? Arlington, VA: American Press Institute. Retrieved from https://www.americanpressinstitute.org/publications/reports/survey-research/trust-journalism-values/

Arraf, J., & Khaleel, S. (2021, September 26). Women Enslaved by ISIS Say They Did NotConsent to a Film About Them. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/26/world/middleeast/sabaya-isis.html

Aufderheide, Patricia. 2012. “Perceived ethical conflicts in US documentary filmmaking: a field report.” New Review of Film and Television Studies 10 (3): 362–386.

Aufderheide, Patricia, Natalie Bullock Brown, Sonya Childress, Molly Murphy, Kameelah Mu’Min Rashad, Sherry Simpson, and Bhawin Suchak. September 2022. From Reflection to release: A framework for values, ethics and accountability in nonfiction filmmaking. Working Films (Wilmington, DE). https://docaccountability.org/framework

Aufderheide, Patricia, and Marissa Woods. September 2021. The State of Journalism on the Documentary Filmmaking Scene. Center for Media & Social Impact, American University (Washington, DC: American University). https://cmsimpact.org/report/the-state-of-journalism-on-the-documentary-filmmaking-scene/

Bennett, W. L., & Livingston, S. (2021). The disinformation age: politics, technology, and disruptive communication in the United States / edited by W. Lance Bennett, University of Washington, Steven Livingston, George Washington University. Cambridge University Press.

Brown, N.B., & Childress, S. (2020, July 9, 2020). The Documentary Future: A Call for Accountability. The Atlantic. Retrieved October 25 from https://medium.com/@sonya.childress/the-documentary-future-a-call-for-accountability-79e7c1315912

Chan, Adamu. 2023. “People, Not Stories: Pathways to Accountability in Prison Documentaries.” Documentary, January 30.

Chattoo, C. B. (2016). The State of the Documentary Field: 2016 Survey of Documentary Industry Members. S. o. C. Center for Media & Social Impact, American University. https://cmsimpact.org/resource/state-documentary-field-2016-survey-documentary-industry/

Childress, S. (2020, June 15, 2020). A Reckoning. The Atlantic. Retrieved October 25 from https://medium.com/@sonya.childress/a-reckoning-526bb97ca60b

FWD-DOC, & Doc Society. (2021). A toolkit for inclusion and accessibility: changing the narrative of disability in documentary film. San Francisco, CA: FWD-DOC. Retrieved from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5dd1c2b5a0f7a568485cbedd/t/602d4708d39c1d1154d0902a/1613581716771/FWD-Doc+Toolkit+small.pdf

Funk, C., Gottfried, J., & Mitchell, A. (2017, September 20). Science news and information today. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.journalism.org/2017/09/20/science-news-and-information-today/

Galuppo, M., & Kilkenny, K. (2022, September 16). Inside the Documentary Cash Grab. Hollywood Reporter. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-features/documentary-streaming-age-filmmaker-debate-ethics-payments-1235221541

Glick, J. (2021). Platform Politics: Netflix, the Media Industries, and the Value of Reality. World Records Journal 5(1). New York: Union Docs. Retrieved from https://worldrecordsjournal.org/platform-politics-netflix-the-media-industries-and-the-value-of-reality/

Gold, H. (2018, June 3). White House plans to nominate conservative documentarian, Bannon ally, to lead government media agency. New York: CNN. Retrieved from https://money.cnn.com/2018/06/02/media/bbg-pack-nomination-plan/index.html

Goldstein, M. (2017, March 31). Bannon built a fortune on right-wing thought and ‘Seinfeld’ reruns. The New York Times, A15.

Gottfried, J., Walker, M., & Mitchell, A. (2020). Americans see skepticism of news media as healthy, say public trust in the institution can improve. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.journalism.org/2020/08/31/americans-see-skepticism-of-news-media-as-healthy-say-public-trust-in-the-institution-can-improve/

Gross, L. P., Katz, J. S., & Ruby, J. (1988). Image ethics: the moral rights of subjects in photographs, film, and television. Oxford University Press. http://www.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/fy0639/88004203-d.html

Gross, L. P., Katz, J. S., & Ruby, J. (2003). Image ethics in the digital age. University of Minnesota Press. http://www.loc.gov/catdir/toc/ecip043/2003009776.html

Hornaday, A. (2021, March 25). Actors in documentaries used to be taboo. Now they’re the stars. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/entertain-ment/documentary-reenactments-operation-varsity-blues/2021/03/25/b67a4cd8-8bea-11eb-9423-04079921c915_story.html

MacDougall, D., & Taylor, L. (1998). Transcultural cinema. Princeton University Press.

Mobina, H., Annette, D., & Lonnie, I. (2016). Think/Point/Shoot: Media Ethics, Technology and Global Change. Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315726267

Nash Information Services. (2021). Box office history for documentary. Beverly Hills, CA: Nash Information Services LLC. Retrieved from https://www.the-numbers.com/market/genre/Documentary

Newton, C. (2020, May 12). How the ‘Plandemic’ video hoax went viral. The Verge. Retrieved from https://www.theverge.com/2020/5/12/21254184/how-plandemic-went-viral-facebook-youtube

Nielsen. (2021). Tops of 2020: Nielsen streaming unwrapped. New York: Nielsen. Retrieved from https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/article/2021/tops-of-2020-nielsen-streaming-unwrapped/

Nielsen. (2011). 10 years of primetime the rise of reality and sports programming. New York: Nielsen. Retrieved from https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/article/2011/10-years-of-primetime-the-rise-of-reality-and-sports-programming/

Noor, D. (2021, April 2). Mike Rowe’s new Discovery+ show is big oil-funded propaganda. Gizmodo. Retrieved from https://earther.gizmodo.com/mike-rowe-s-new-discovery-show-is-big-oil-funded-propa-1846585716?utm_source=gizmodo_newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=2021-04-02

Ouellette, L. (2020, June 17). Cancelling COPS, Film Quarterly Quorum. Retrieved from https://filmquarterly.org/2020/06/17/cancelling-cops/

Rangan, P. & Story, B. (2021). Four propositions on true crime and abolition, World Records Journal, Vol. 5. Retrieved at https://worldrecordsjournal.org/four-propositions-on-true-crime-and-abolition/

Rosner, J. (2021, July 15.) A Haunting New Documentary About Anthony Bourdain. The New Yorker. Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com/culture/annals-of-gastronomy/the-haunting-afterlife-of-anthony-bourdain/

Ruwer, R. (2020, April 9.) Why ‘Tiger King’ is not ‘Blackfish’ for big cats. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/09/science/tiger-king-joe-exotic-conservation.html

Schulz, K. (2016, Jan. 17). “Dead Certainty: How Making a Murderer goes wrong,” The New Yorker. Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/01/25/dead-certainty

Schwab, T. (2020, August 21). Journalism’s Gates Keepers. Columbia Journalism Review. Retrieved from https://www.cjr.org/criticism/gates-foundation-journalism-funding.php

Schwab, T. (2019, December 20). Documentaries as advertising. 100 Reporters. Retrieved from https://100r.org/2019/12/documentaries-as-advertising/

Sanders, W. (2012). Participatory spaces: Negotiating cooperation and conflict in documentary projects. Utrecht, The Netherlands: University of Utrecht.

Williams, R. H. (1997). Cultural wars in American politics : critical reviews of a popular myth / Rhys H. Williams, editor. Aldine de Gruyter.

Winston, B. (2000). Lies, damn lies and documentaries. London: British Film Institute Publications.

Yachot, N. (2022, October 23). ‘The actual critique is being lost’: the truth about Jihad Rehab, the year’s most controversial documentary. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2022/oct/23/jihad-rehab-documentary-making-unredacted-saudi-arabia

Weideman, Reeves. 2023. “The boom—or glut—in television documentaries has sparked a reckoning among filmmakers and their subjects.” Vulture, February 1. Online.